Eventually, every “grownup” animated series does its obligatory anti-censorship episode. Maybe, at one point, it was because producers of such series all had similar experiences (i.e. angry parents who’d mistaken the series as suitable for their kids); but by now it feels more like something that’s simply expected of the genre.

There’s certainly variety to be had in the way the issue is played out: Family Guy had the FCC invading Quahog and attempting to extend their censorship goals to real-life happenings. Beavis & Butthead injured themselves imitating a TV show – but it was a PBS documentary about Ben Franklin. Duckman was enlisted to save the world of stand-up comedy from a suspicious trend toward cleanliness. South Park has turned this routine into something of a speciality; producing multiple self-righteous variations on the theme (it was even the plot of South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut), where the only thing that ever changed was which group Trey Parker and Matt Stone felt were out to get them at that particular moment (helicopter parents, Scientology, celebrity political activists, people who don’t want you to draw Muhammad, etc).

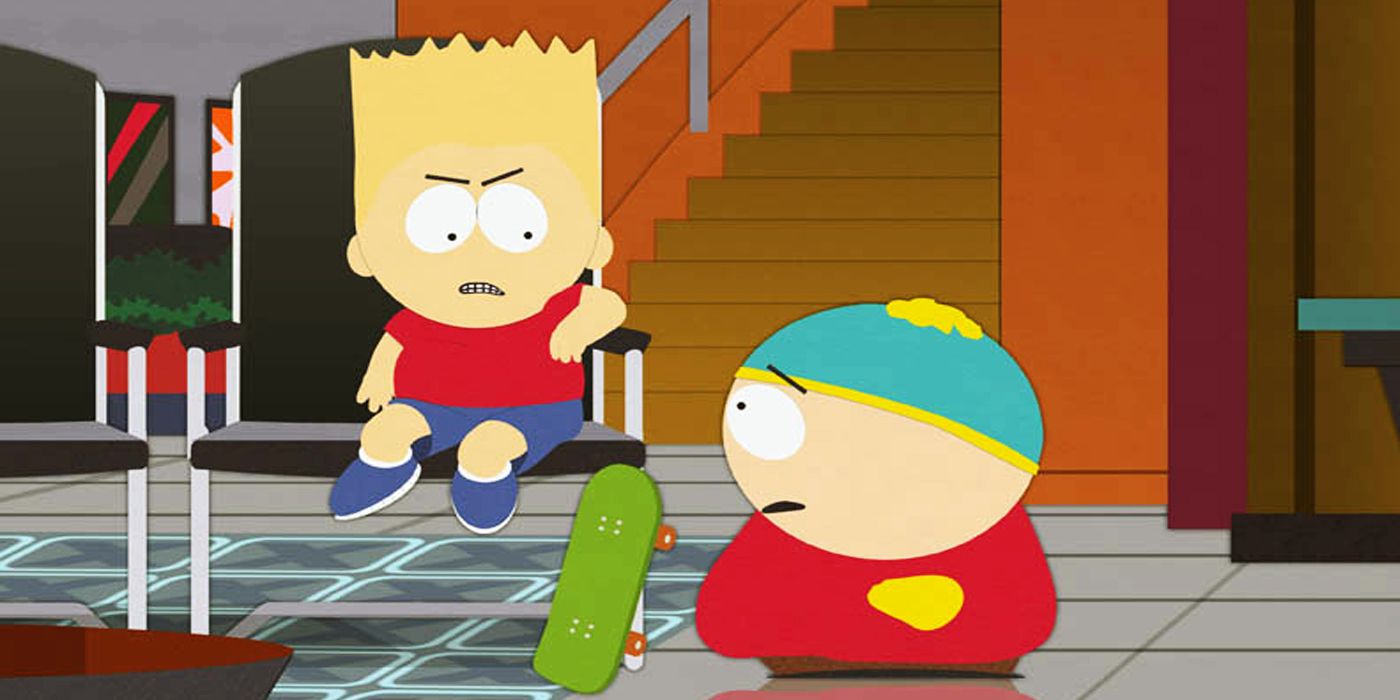

These episodes tend to be very funny, but they also often have surprisingly short pop-cultural shelf-lives; too wedded to passing controversies and built too much off the personal grudge-holding of writers and producers to maintain a proper grip on the public consciousness – especially in terms of whatever message they were trying to send. The main things people tend to remember about South Park’s 2006 “Cartoon Wars” mini-epic are Cartman teaming up with an expy of Bart Simpson, and Parker and Stone’s assertion that rival series Family Guy was scripted by manatees… but that the big throwdown was all about whether or not Comedy Central would “let” them do jokes about Islam? Not so much (ditto Kyle’s plaintively earnest “It’s all okay, or none of it is!” moralizing.)

But there is one such episode that still holds up after all these years, despite being older than any of the others (in fact, it might well be the progenitor of the entire cycle – patient zero) and hailing from a series that never truly set out to merely “shock” in the first place. Naturally, we’re talking about The Simpsons’ take on the subject, Season 2’s 9th episode: “Itchy & Scratchy & Marge.”

S.N.U.H. FILM

The episode is considered a standout classic, even among the rest of The Simpsons’ highly lauded first ten seasons, so it’s likely you remember the plot by heart: Baby Maggie injures Homer with a mallet blow to the head, which Marge subsequently discovers is the result of her imitating the antics of Itchy & Scratchy – the cat and mouse cartoon team whose shorts run as part of the Krusty the Clown Show.

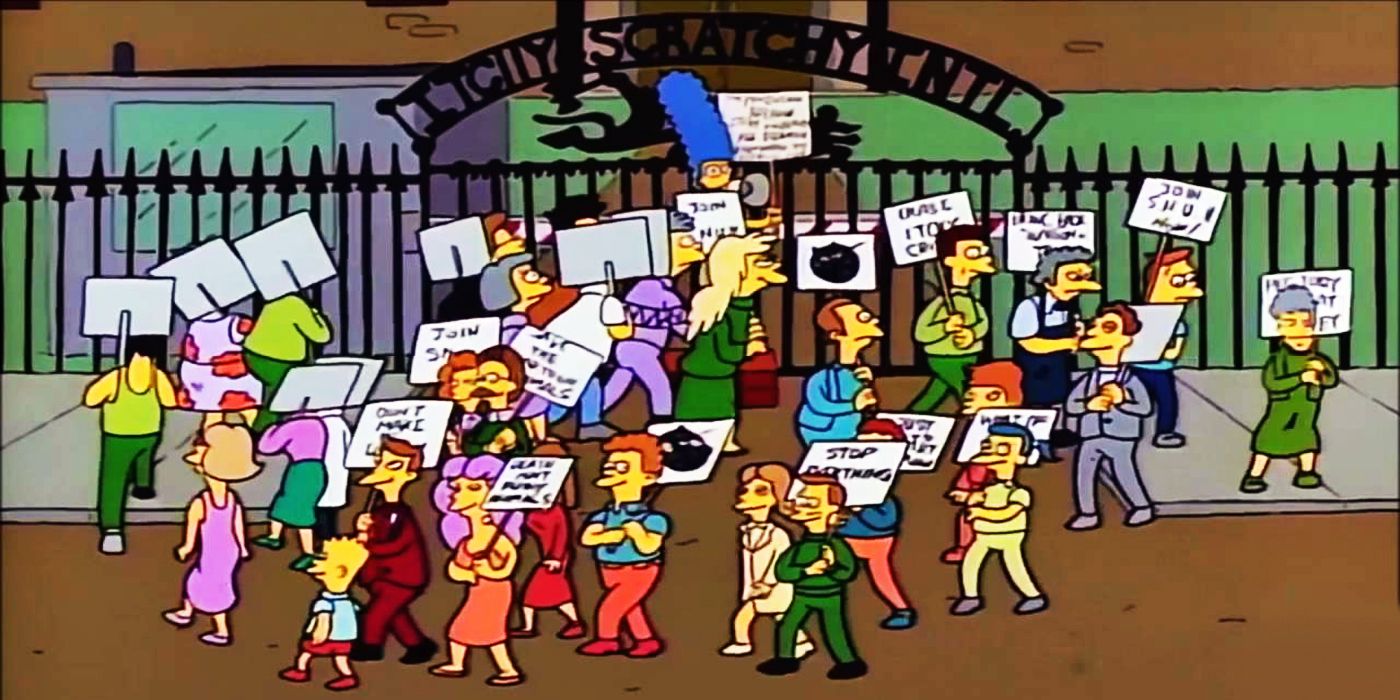

After having her (fairly passive) letter of complaint rudely rejected by the cartoon’s producer Roger Meyers Jr. (Alex Rocco, making his debut in the role), Marge haphazardly unites Springfield’s other concerned mothers into a protest group, S.N.U.H: Springfieldians for Nonviolence, Understanding and Helping. Together, they successfully cow the animation studio into reworking Itchy & Scratchy into a friendly series so saccharine that its fans are driven to abandon TV and rediscover the joys of idyllic outdoor play.

But, in a glib final twist characteristic of early Simpsons’ exasperated take on on the failings of good intentions, Marge doesn’t get to rest on her laurels. The rest of S.N.U.H. organizes to protest the arrival of Michelangelo’s David at the Springfield Museum (they object to the nudity), and Marge is forced to concede that she can’t object to censoring one creative work while supporting the same for another. Itchy & Scratchy return to normal, Springfield’s children are drawn back to television and The Simpsons’ world goes back perfect imperfection.

“DONT DO THAT!”

So why does “Itchy & Scratchy & Marge” endure like a Twinkie where other shows’ attempt to tackle the subject age more like poorly preserved cheese? The main reason is likely the writing: The Simpsons was so far out ahead of every other network sitcom (animated or not) at this point in time that it was barely even a contest, and this particular piece was an early gem from enigmatic fan-favorite writer John Schwartzwelder. Simply put, no one should be surprised that a series routinely cited as one of television’s greatest creations would outgun its rivals and imitators.

It also probably helped that the makers of The Simpsons were able to approach the issue from their usual position (above the fray, observing and mocking the ridiculousness of humankind), rather than opting to play defense. Detractors of The Simpsons in this era were mainly focused on the show’s Bart-centric kiddie-merchandising empire than the show itself, and by most accounts the episode was based more on the public assault on fellow Fox Network staple Married, With Children, which really was led by an ultra-religious housewife whose campaign against the raunchy sitcom gained brief national media attention.

By contrast, other series that have taken up similar storylines tended to do so in reaction to direct challenges to their own product and, as such, lack a certain amount of nuance – however well disguised. Family Guy’s “PTV” starts out broadly mocking the FCC overreaction to the Janet Jackson/Justin Timberlake Super Bowl Halftime “wardrobe malfunction” incident, but it quickly becomes all about Seth MacFarlane and his writers bracing at the way that overreaction was felt by their newly-returning series (the episode’s setpiece is an anti-FCC musical number that climaxes with a montage of edge-skirting gags from the earlier incarnation of the show.)

Likewise, South Park’s “Cartoon Wars” is all about lionizing Parker and Stone’s position on the “Muhammad cartoon” controversy as not only a righteous position, but the only righteous position. The only notable opposing voices being heard are from Al Qaeda terrorists and Eric Cartman, who doesn’t actually care about the issue outside of manipulating it to destroy Family Guy, which he views as an inferior pretender to his personal brand of humor. That’s not to say that any work of fiction tackling a controversial subject is obliged to play at false objectivity or indulge in the “Golden Mean Fallacy” (where both sides are held wrong against a hypothetical centrist view), but moral binary tends to create narratives that don’t hold up to scrutiny (or over time) – especially when everyone knows you’re casting yourself as the good guy.

Unsurprisingly, “Itchy & Scratchy & Marge” features a prescient gag at the expense of this very tendency: At the very moment that Marge is wavering on the efficacy of her campaign, the animators decide to escalate the situation by having their cat and mouse duo declare a momentary detente to decapitate a scolding squirrel sporting her signature hairdo. The next day, Marge appears on Smartline with Kent Brockman and instructs viewers to inundate I&S International with angry mail – briefly bringing the “classic” version of Itchy & Scratchy to an end.

“THE SCREWBALLS HAVE SPOKEN.”

That moment (the squirrel) is a sly bit of brilliance in an episode made of them, deftly playing Marge’s endearing incompetence as a DIY-activist (her protest sign reads, in full: “I’M PROTESTING BECAUSE ITCHY & SCRATCHY ARE INDIRECTLY RESPONSIBLE FOR MY HUSBAND BEING HIT ON THE HEAD WITH A MALLET”) with the sheer obnoxiousness of the animators. The short, prior to “Squirrel Marge” arriving, appears to consist of little more than a loop of the protagonists hitting each other with baseball bats, and the cartoonist who’s inspired to add her chuckles in smug self-satisfaction at what we soon see is a pretty stupid joke – even by Itchy & Scratchy standards. S.N.U.H. is hapless, I&S are shameless – what a tragically absurd place Springfield is.

Of course, it’s not surprising that The Simpsons wouldn’t make Roger Meyers and his cadre of lazy animators (“Oooh, make it a pie. Pies are easier to draw”) the heroes of the story, even though they’re the ones who ultimately get to “win” and the story is being conceived by fellow mischievous cartoon makers. After all, they were never designed for self-flattery. Itchy & Scratchy (and Krusty, for that matter) were always meant to be terrible, poorly made television. The show did such a perfect job recreating the addictive vapidity of most childrens’ programming that if you started watching The Simpsons at roughly Bart and Lisa’s respective ages, you could easily wind up sharing their affection for a Bozo-wannabe embodying the totality of the “hack comedian” archetype, and the sub-Tom & Jerry time-filler he shilled between commercials. Viewed with adult eyes, however, the satire is clear… and merciless.

In fact, that was the entire joke of perennial villain Sideshow Bob’s origin story (in the season 1 episode “Krusty Gets Busted”): The bad guy who frames an innocent man and steals his livelihood actually does end up providing a vastly superior, intellectually-nourishing show in its place – one that truly aims to respect and nurture its child audience. The episode ends with this bad guy being hauled off to jail shouting, “Treat kids like equals, they’re people too! They’re smarter than what you think – they were smart enough to catch me!” – and Bart’s victory is the restoration of something that he absolutely loves, which also happens to be awful. Order is restored… and it’s kind of crummy. The Simpsons ethos, in a nutshell.

“I GUESS ONE PERSON CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE… BUT MOST OF THE TIME, THEY PROBABLY SHOULDN’T.”

That sort of tragicomic approach is, ultimately, the secret to why “Itchy & Scratchy & Marge” continues to take every other anti-censorship episode to school. It plays the issue with a sincere even-handedness that’s easy to mistake for South Park’s increasingly grating “both sides”-ism (or Family Guy’s “equal-opportunity offender” handwave), but is in fact much more nuanced and thoughtful (and, just as importantly, funny). Few other series would even attempt to do an anti-censorship episode where the censorious mom was the most sympathetic character, or to come down on the side of free-expression while still positing that the “expression” in question for the bulk of the episode is mindless trash that the world is probably better off without. Remember, when the kids of Springfield switch off the sanitized Itchy & Scratchy, what they wake up to is a wish-dream of endless-summer idyll straight out of Tom Sawyer (or Dandelion Wine) scored to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony.

Lest we forget, the biggest lightning-rod of the censorship debate even today – “imitable acts” – is (at least in the case of this episode) quite definitively a real concern in the world of The Simpsons. Maggie was, in fact, acting out a gag from Itchy & Scratchy when she walloped her father with the mallet, and when she later watches the restored Itchy and Scratchy shooting each other with comically large revolvers, she responds by picking up a toy gun and firing it at a photo of Homer. It’s hard to imagine any similar show made today even thinking about being so matter-of-fact regarding that aspect.

But it’s precisely that unexpected approach (unexpected mainly because the writing staff of a comedy show like The Simpsons is unlikely to be on the side of banning vague obscenities from a cartoon) that makes the episode so resonant. Marge’s quest might be “wrong,” but her concerns are utterly sympathetic and her appraisal of Itchy & Scratchy is spot on. Like many of The Simpsons‘ best storylines of the era, the episode is, at its core, about enduring the absurd minor tragedies of everyday existence: Itchy & Scratchy will continue to be trash, Bart and Lisa are once again glued to it, it’s a terrible influence on Maggie, and Marge was humiliated on national television for trying (however wrongheadedly) to do what she thought was the right thing. But, on the other hand, Springfield gets to see Michelangelo’s David, and free speech technically won the day – so maybe it’s not all bad.

“Itchy & Scratchy & Marge” sets itself up to juggle a lot of balls for a half-hour cartoon sitcom, especially in the less-than-wonderful world of network television circa-1990. A “damned if you do” tragic farce that asks its audience to sympathize with a character whom the narrative openly acknowledges is in the (ideological) wrong, holds up their opponent as charlatans to be mocked, and also asserts the justice of said charlatans’ “victory” before ultimately going out on a complex moral denouement.

That’s why “Itchy & Scratchy & Marge” still works, and it’s why we still keep coming back to The Simpsons – even after nearly three decades on TV.

The Simpsons Season 28 premieres tonight on FOX.