Over the past few years, both Amazon Prime’s Good Omens and Netflix’s The Sandman have featured anthropomorphized versions of death, each of whom presents quite differently despite Neil Gaiman’s hand in both. While including death as a character is nothing new in stories and media, the presentation of one of humanity’s greatest fears and one of its few truly shared realities reflects much about a culture’s values and core elements. But beyond using death as a sounding board to understand others, varied depictions of death in art is also a mirror by which audiences can process mortality and its many facets, both their own and those around them.

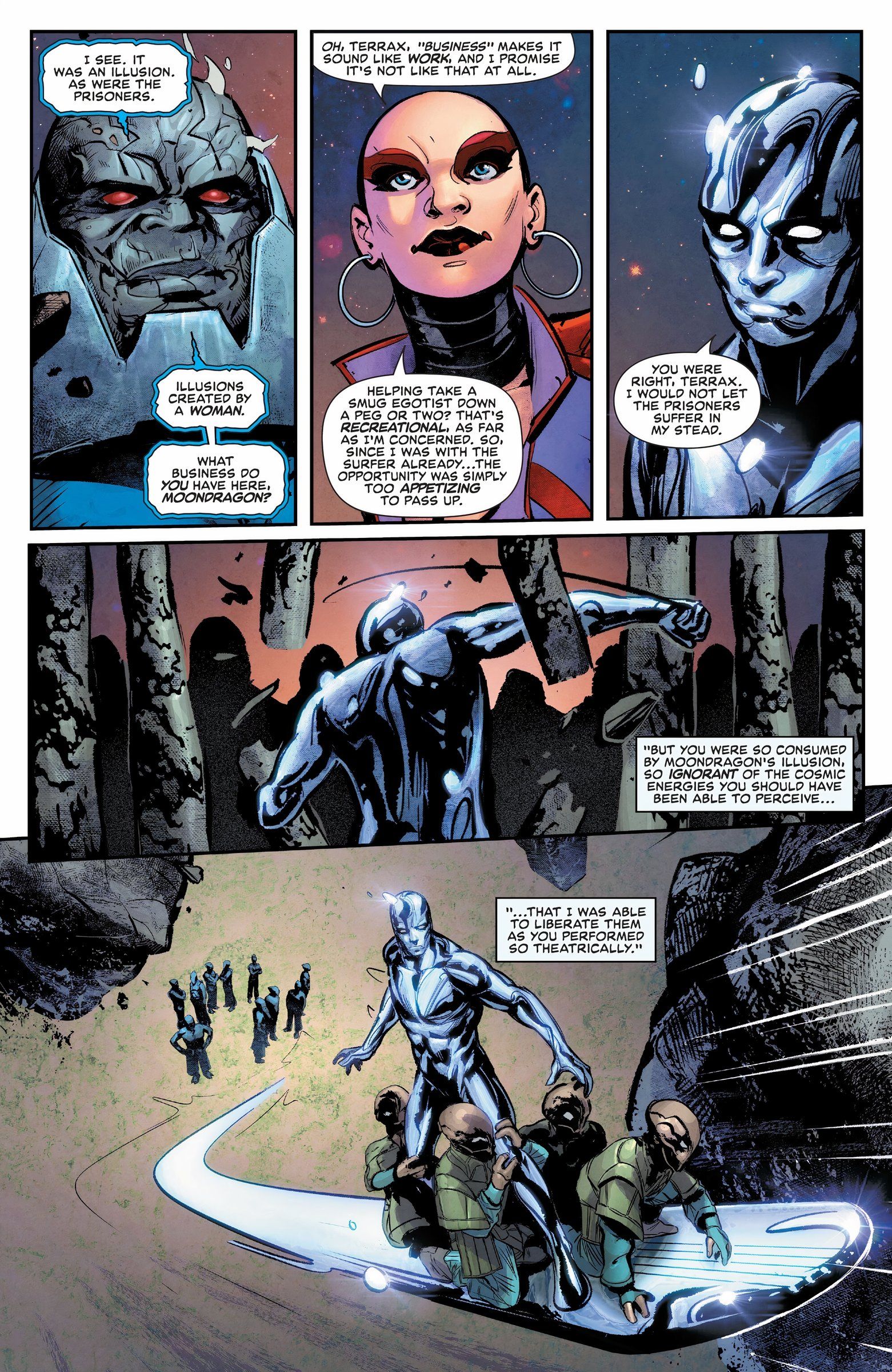

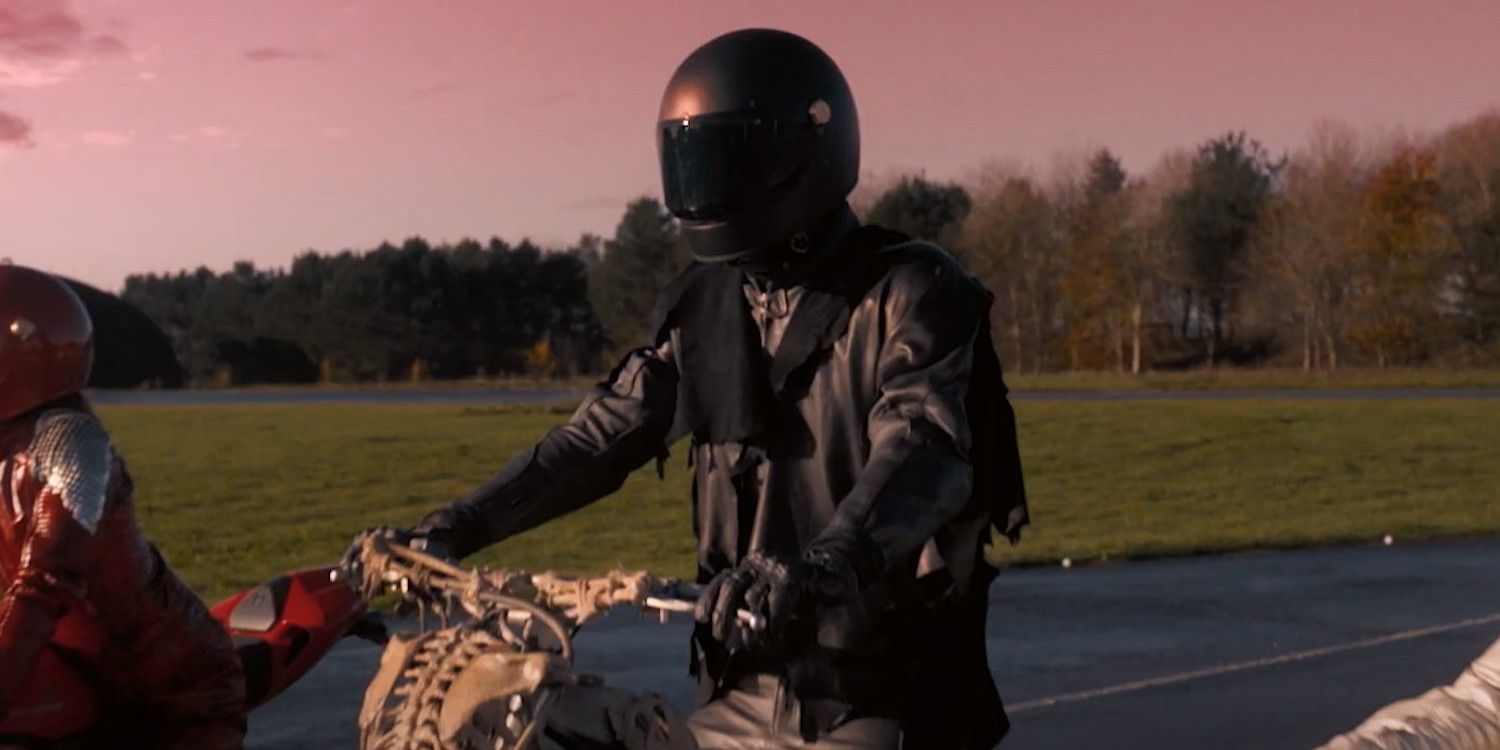

In The Sandman, Death (Kirby Howell-Baptiste) is one of the seven Endless, conceptual entities embodying experiences that have existed since the first instance of sentience. In Gaiman’s conception of Death, she is the second oldest after Destiny, but of The Sandman‘s characters she behaves with none of the gravitas and formal presentation of her younger brother, Morpheus (Tom Sturridge). Instead, she is affable and empathetic, and of her siblings she is perhaps the most connected to humanity. Meanwhile, the portrayal of Death (Brian Cox/Jamie Hill) in Good Omens primarily serves as one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse summoned by the coming of Adam (Sam Taylor Buck) the antichrist. His face is seldom seen behind a dark biker’s helmet, and while he can be witty and charming, he still holds a fearsome skeletal countenance and interacts most comfortably with his fellow horseman. Even among other depictions of death in media such as Lady Death, who was teased in Thor: Love and Thunder, these two iterations are unique in certain ways. In presenting each of these two versions of Death side by side, the differences are marked: although both wear black, one presents as a female and the other as male, one wears a helmet while the other never covers her face, and one has dark skin while the other is only bone.

How The Sandman’s version of Death came to be so different than Good Omens’ can be explained for several reasons, even though the same author helped create both characters. While Terry Pratchett also helped create the Death seen in Good Omens, with his iteration of the character that was often featured in the Discworld series coloring its depiction in his and Gaiman’s collaboration, it’s not the only reason the portrayals differ so widely. While both Good Omens and The Sandman use convoluted plans and lean on known mythology, the differing tones, themes, and purposes of each story require different death portrayals depending on their role in each story.

Why Death Is Different In The Sandman & Good Omens

The late Terry Pratchett’s role in Good Omens is distinctive and celebrated, as his humor and relatable style of writing brought much of the comedy to the difficult topic of judgment day. Good Omens exhibits many of Pratchett’s trademark elements, particularly in the Angel of Death, including Death’s dry wit and the visual cue of his fully capitalized speech. This greatly contrasts with Gaiman’s often darkly mythic, atmospheric stories with grotesque fears and deep shadows, even in his novels meant for younger audiences such as the inventive, Tim Burton-esque Coraline and The Ocean at The End of the Lane. Meanwhile, Pratchett’s work plays with absurdity in life and in fantasy, which he contributed to his take on Death, and which was still present in his and Gaiman’s portrayal of the concept in Good Omens. This makes The Sandman’s iteration fundamentally different than the one in which Gaiman’s was the primary hand.

Good Omens’ Version Of Death Isn’t Meant To Be Human

However, beyond authorial stylistic differences in The Sandman and Good Omens’ portrayal of Death, the two characters are so different because the Death of Good Omens isn’t meant to be a creature that humanity, and audiences, can relate to. From the hidden face to the grandiose, alien voice and the empty eye sockets behind his helmet, Death is truly the final of Good Omens‘ four horsemen of the apocalypse. He heralds the end of the world, a calamitous event, a prospect that’s meant to be existential and painful despite the humorous tone of Good Omens. As such, Death needs to be characterized as something as inhuman as possible to match the stakes of the novel. He is the antithesis of the humanity that Crowley (David Tennant) and Aziraphale (Michael Sheen) exhibit and develop throughout the story, further feeding the idea that even if people should be as different from each other as an angel and a demon, they are always closer to each other than to the cold hand of mortality.

Death Needs to Be Approachable in The Sandman

While Death is a herald of the apocalypse in Good Omens, The Sandman takes a much more grounded approach to the character. Season 1 of The Sandman’s Death and Dream isn’t a story about the death of the world, instead, it depicts how death is a part of life. While it is still inevitable and final, it is also inextricable from existence, and as such, Gaiman’s Death needs to feel different from that of Good Omens. This is why Death isn’t fearsome and macabre in The Sandman. She wears comfortable clothes and hides nothing in her manner or presentation. To make Death as quotidian and present as it is in real life, she needed to be approachable, and nearly human herself. She even seems deeply relatable in how she treats Dream as a sibling, both in caring for him, mocking him, and calling out his flawed ideas when need be. These aspects drive home the point that Death explains to Dream about the Endless once he retrieves his tools: That they need humanity as much as humanity needs them. Otherwise, the Endless wouldn’t manifest in as human of a way as they do.

Death Isn’t Meant to Be Final in The Sandman

Finally, one of the key differences in The Sandman’s Death is that Death’s role is not necessarily final. Even her arrival doesn’t result in immediate tragedy. When Gaiman’s death takes people, she tends to speak with them before going about her work, even sometimes giving them a few more moments of life to pray or prepare. Even more so, The Sandman is always careful to hide what exactly happens once a person’s soul is free. There’s little more than the sound and shadow of wings, and when characters ask Death what will happen to them now, Death merely responds that they’ll find out “what’s next.” But this uncertainty is not tinged with fear in The Sandman. Instead, Gaiman’s kind Death depicts it moving on as peaceful, making this ambiguity seem like the next step. Once again, while Death in Good Omens leads to the terror and finality of celestial war, Death in The Sandman is yet unknown.

While both The Sandman and Good Omens are both tales that grapple with mythology, purpose, choice, and endings, they set their conflicts against wildly different backdrops. Good Omens‘ ending is filled with a certain degree of farce combined with strong messages in the face of total death, and The Sandman depicts a closer, intimate portrait where it is impossible to avoid personal mortality, only to greet it with grace. These differing portrayals are reflected in the versions of Death each story uses in correlation with its needs. This, in turn, depicts the varying elements and facets in which audiences can and must reckon with mortality in their own lives, where they might meet whichever version of Death they need most to see.