Andor is the fourth Star Wars series to launch on Disney+, but it’s the best-looking Star Wars show yet. Shows like The Mandalorian or Obi-Wan Kenobi bring the Star Wars aesthetic to the small screen and look mostly great, but despite the high production value of these, certain elements end up looking oddly cheap.

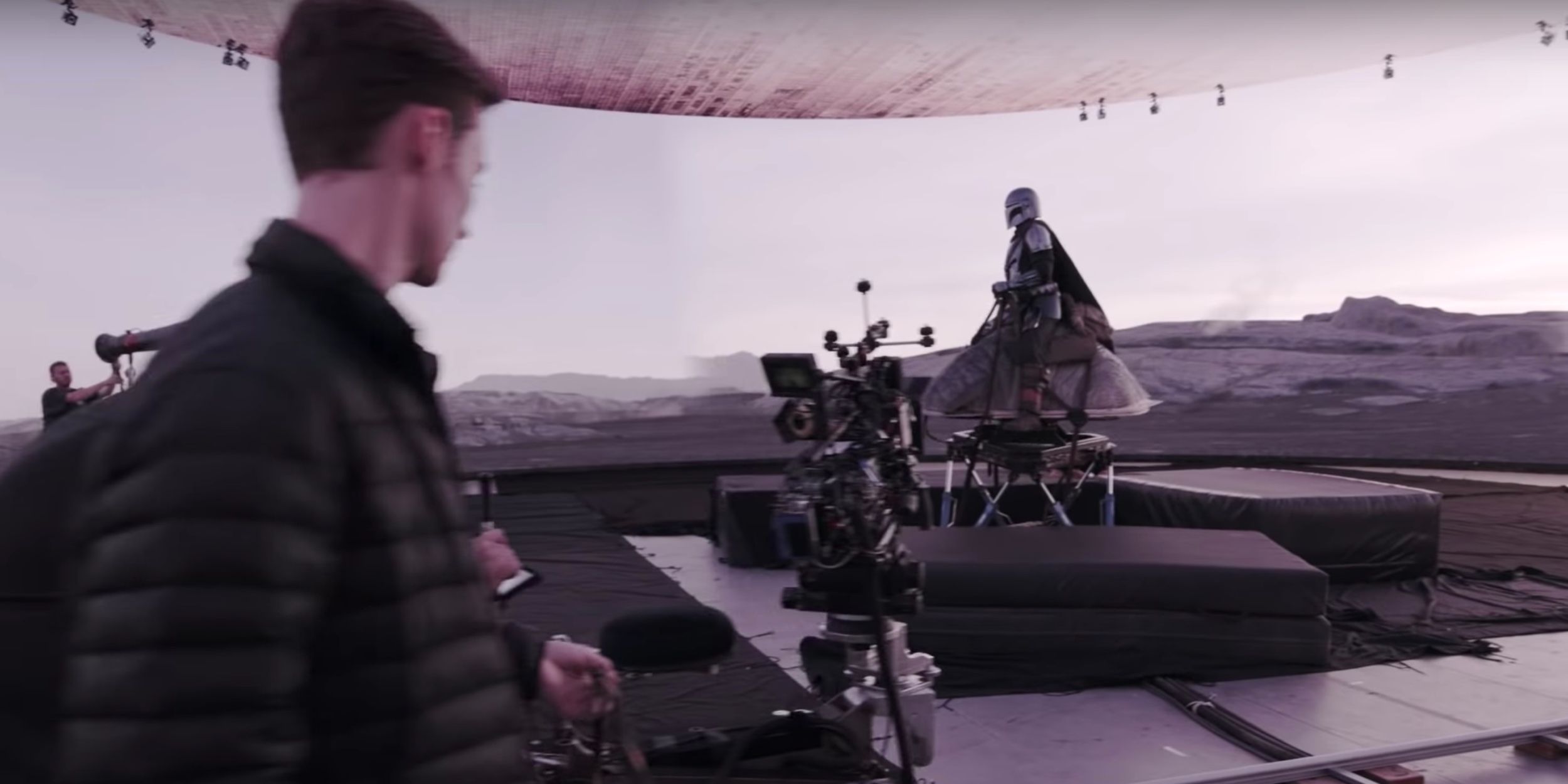

Star Wars has always set a new bar for cinematic spectacle, blazing new trails for visual effects, often creating new technology to get it done. The Mandalorian continued that tradition with the introduction of StageCraft, AKA “The Volume,” a soundstage with LED panel walls that has been used in every Star Wars show so far except for Andor.

While The Volume’s LED walls allow the filmmakers to simulate almost any set, creating realistic-looking environments without the trouble of blue or green screens or the expense of travel and building practical sets, it still has some flaws. Since Andor is the first Disney+ Star Wars show to eschew The Volume in favor of actual location shooting, the series’ production value stands in sharp contrast to the other Disney+ Star Wars shows.

How Star Wars’ Use of The Volume Improves on Blue Screen and CGI

The Volume is a massive leap forward in filmmaking technology in a number of ways. Compared to traditional green screen, The Volume creates the near-final look of the scene while it’s being shot on set, meaning actors don’t have to work solely from their imagination, directors can make more creative decisions as the scene is shot, and it even makes lighting and reflections look more natural. This is especially convenient for shows like The Mandalorian where the reflective helmet worn by Din Djarin would typically pose a tedious task for VFX artists of carefully replacing green screen reflections in the helmet. Instead, the helmet reflects the environment pictured on The Volume’s LED screens, which is far more convenient for everyone involved.

The StageCraft technology created with The Volume isn’t just a product of the screens, though. There’s also an interface with the cameras so the backgrounds shown on the LED walls shift dynamically depending on the camera angle to give a parallax effect to maintain a sense of perspective. With a blue screen, this sort of effect is created in post-production to match camera motion, and while the end result can still be great depending on the planning and shot design worked out with the director and VFX supervisor, the final look only exists in the imagination of everyone on set. Clearly, The Volume is an impressive tool that solves a lot of complications posed by traditional blue screen or green screen, although it’s still not a perfect solution.

Why Star Wars’ Use Of The Volume Has Limitations

The Volume is a huge step forward in many ways, but it’s not without its limitations, and sometimes those limitations result in a cheaper-looking end product. Interestingly, many of these issues, as with blue screen and green screen, are less related to The Volume’s capabilities as a tool and are actually a product of the creative decisions made by filmmakers working with the tool.

Foundationally, the biggest issue with StageCraft technology is the fact that it’s ultimately still a stage, therefore nearly 100 percent of the realism is still dependent on the cast and crew. Dynamic lighting, wind effects, dust and debris, and etc. are all factors that need to be artificially created. StageCraft technology means the creative team can get more ambitious with the types of scenes they shoot in The Volume, but that also raises the bar on accompanying environmental details, making any mismatch seem that much more jarring. This isn’t a unique problem to The Volume, but the ease of production means the filmmakers put less of a priority on masking the technology in the shot’s design as they would with green screen.

The fact that The Volume is ultimately still a stage also influences the way scenes are staged and blocked. How many actors are actually in the scene, where they stand, where they move, what set elements they interact with, and where the camera is located are all impacted by this. So, while a scene might take place in a large hangar with dozens of stormtroopers walking around in the background, the actual shot may only show a few characters interacting with each other as they would in a stage play with an exceptionally detailed backdrop, creating a sort of “uncanny valley” effect where the set appears realistically big, the character and environmental interactions still feel like they’re shot on a smaller stage.

A similar complication arises when editing scenes, particularly when a character is moving around a location. An example of excellent execution in The Volume is Din Djarin’s introduction in Chapter 5 of The Book of Boba Fett. The excellently designed shot is an almost two-and-a-half minute “oner” tracking shot featuring an injured Mando limping onto an elevator, taking the elevator up, walking through a nightclub to a VIP room where the camera circles around the table during a conversation before following Mando as he limps back to the elevator and takes it back down. It would be a well-designed shot under any circumstances, but the fact that it was all shot in The Volume without an elevator makes it that much more impressive. Conversely, poor shot design and editing creates glaring issues, such as Reva’s parkour run across the rooftops in Obi-Wan Kenobi where there’s no consistency to the background and obstacles seemingly appear and disappear, creating massive continuity errors every time the camera cuts to a new angle.

Why Andor’s Practical Production Looks Better Than Other Star Wars Shows

The fact that these issues arise in Star Wars shows is particularly ironic since Star Wars’ iconic look and feel is largely derived from creative decision-making driven by budget constraints. The Star Wars prequels are notoriously criticized for their use of green screen and CGI, but those issues commonly arise from boundary-pushing fantastical elements, while many of the more subtle uses of CGI and other tricks go unnoticed. One of the biggest complaints about Lucas’s approach to the Star Wars prequels was that he would rely too much on digital tools to solve problems instead of finding more innovative solutions like he did with the original trilogy. Interestingly, we see some of this same dichotomy at play with Andor.

Since Andor is mostly shot on location, there’s a number of immediate and clear improvements over The Volume. Even shooting on location is a sort of “simulated reality” since wind, lighting, and other environmental conditions are frequently still fabricated, but there’s an added sense of tangible realism since it’s being fabricated outdoors on a real set instead of on a clean, static soundstage.

Additionally, since all the sets are real, that means the sets are way more interactive, meaning characters can interact more with the environment and it’s easier to maintain a sense of logistics in editing since the environments actually exist and aren’t being assembled digitally. However, since these environments don’t actually exist in the Star Wars universe (like the digital environments used in other Star Wars shows produced with The Volume), the filmmakers have to employ movie magic to make them look that way, meaning set design, cinematography, and editing are all at work to make a real-world environment feel like it belongs in a galaxy far, far away. This might be harder to execute than it would be to simply shoot an artificial environment in The Mandalorian, but the constraints ultimately result in a more tangible and believable aesthetic.

Ultimately, StageCraft is an amazing new technology and filmmakers can use The Volume to do impressive things, but like the use of blue screen and green screen, that doesn’t always translate into a better final product. As the technology evolves and filmmakers learn how to apply it, it’ll only look better and better, but it’s ultimately just another tool for filmmakers to use. Andor‘s use of practical locations isn’t only good because it results in the best-looking Star Wars series yet, but because it shows Disney and Lucasfilm aren’t mandating a one-size-fits-all approach to the production of Star Wars shows, leaving filmmakers to use the tools most suited for the job.