The beloved creator of genre-shaping comics such as Watchmen and V for Vendetta, Alan Moore famously left superheroes – and ultimately the entire comics industry – behind, moving on from the medium he helped define to embrace prose writing in projects such as Jerusalem and the recently released Illuminations, now available in paperback from Bloomsbury Publishing. Now, Moore sits down with Screen Rant to discuss his prose, as well as his larger perspective on modern popular entertainment and its effect on the world.

In the first half of this in-depth interview with Screen Rant, Moore discussed his disappointment with modern fantasy (including Game of Thrones), the sinister values underlying superhero stories, and the relationship between nostalgia and fascism. Now, the acclaimed writer moves onto what makes his prose so unique, the death of counterculture, and how to fix popular entertainment.

Alan Moore Discusses the Boundary Between Fiction & Reality

Moving on to your ’50s Beat-inspired story from Illuminations, ‘American Light,’ it was interesting to see you deconstruct the historical period and its beloved figures, like Kerouac.

Alan Moore: It came about because I’ve been interested in the Beats for a number of years, particularly over these last few years where I’ve been a recipient of – over here we’ve got a splendid, heroic gentleman called Kevin Ring, who publishes a thing called Beat Scene, and he’s been publishing it since the 1980s. The love of the Beat scene is alive and well over in England. So, I’ve been absorbing all of these fascinating articles about not only the Beats that everybody knows about and remembers, but all of the other ones who’ve been forgotten or neglected because everyone tends to think, ‘yeah the beat writers, that’s Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs.’ Even giants like Ferlinghetti can get squeezed out, let alone people like Lew Welch or Kirby Doyle. [Doyle’s] book Happiness Bastard, it’s brilliant. It’s the only novel he wrote, but he was a Beat poet and a very good one. Very funny.

So, I thought, ‘I want to write something that is a tribute to the Beats and also is talking honestly about the other side of the Beat experience,’ you know, that it wasn’t a bundle of laughs for the women. Carolyn Cassidy had said in a couple of her books, and Joyce Johnson. The ’60s, immediately after the Beat era, the psychedelic movement that I came from, that treated women appallingly. It was just starting to get the idea that maybe it shouldn’t. Back in the ’50s, there were some brilliant women Beat poets, Diane di Prima, but they never really got the attention of the males. There were also a couple of black Beat writers who didn’t tend to get the attention. And the working-class Beat writers were by-and-large overlooked. It was largely the province of educated people from middle-class backgrounds.

And yet, there were some wonderful things accomplished by the Beat movement, things that I benefited from. I mean, I was reading the major Beats when I was a teenager and a young man, and that was hugely influential. I wanted to somehow capture all of this, so I thought, ‘right, what I’m going to have to do then is to do a short story that is actually a Beat poem. So, I’ll have to invent a Beat poet, and then write a credible Beat poem by that poet, and, as it turned out, a poem that could believably have restored his reputation after a few years in decline.’ And I thought then, ‘and then I’m going to have to invent another voice to criticize that poem, and probably a third voice when the person criticizing the poem compares the first poet’s work with that of another unpublished Beat writer, who I’ll also have to invent.’ And I thought ‘well, this sounds tricky, but it does sound like a challenge.’ That was an awful lot of fun. Well, I don’t suppose everybody would call it fun, but I certainly enjoyed it.

I was utilizing a lot of [my wife] Melinda’s knowledge of San Francisco, and also the immense amounts of research material that I’ve got stacked up around me. But I think I did a credible job of San Francisco, and managed to talk about quite a lot of the Beat experience from different angles. And also, I was quite pleased with it as a short story because, until you’ve reached the last word of the footnotes, you haven’t got the story. I thought that was good, that it’s the very last line of the footnotes that actually explains the whole of the story, of why it’s been written. Why this person has decided to do this appreciation of the poem ‘American Light.’ Playing literary games I’m sure, and would be of absolutely no interest to most people in the world, but I find this sort of stuff thrilling, and, just, really challenging to try and write something that sounded like a Beat poem. And the best compliment that I’ve had on that one was when I got a message from Kevin Ring himself, the editor of Beat Scene, saying that he’d had to check to make sure that Harmon Belner and Connor Davey weren’t real. That they weren’t somehow Beat writers that he’s somehow overlooked, and that was a real compliment. I was thrilled by that. If I can pull the wool over a Beat expert’s eyes, then I must be doing it right.

That’s amazing, given its satirical tone.

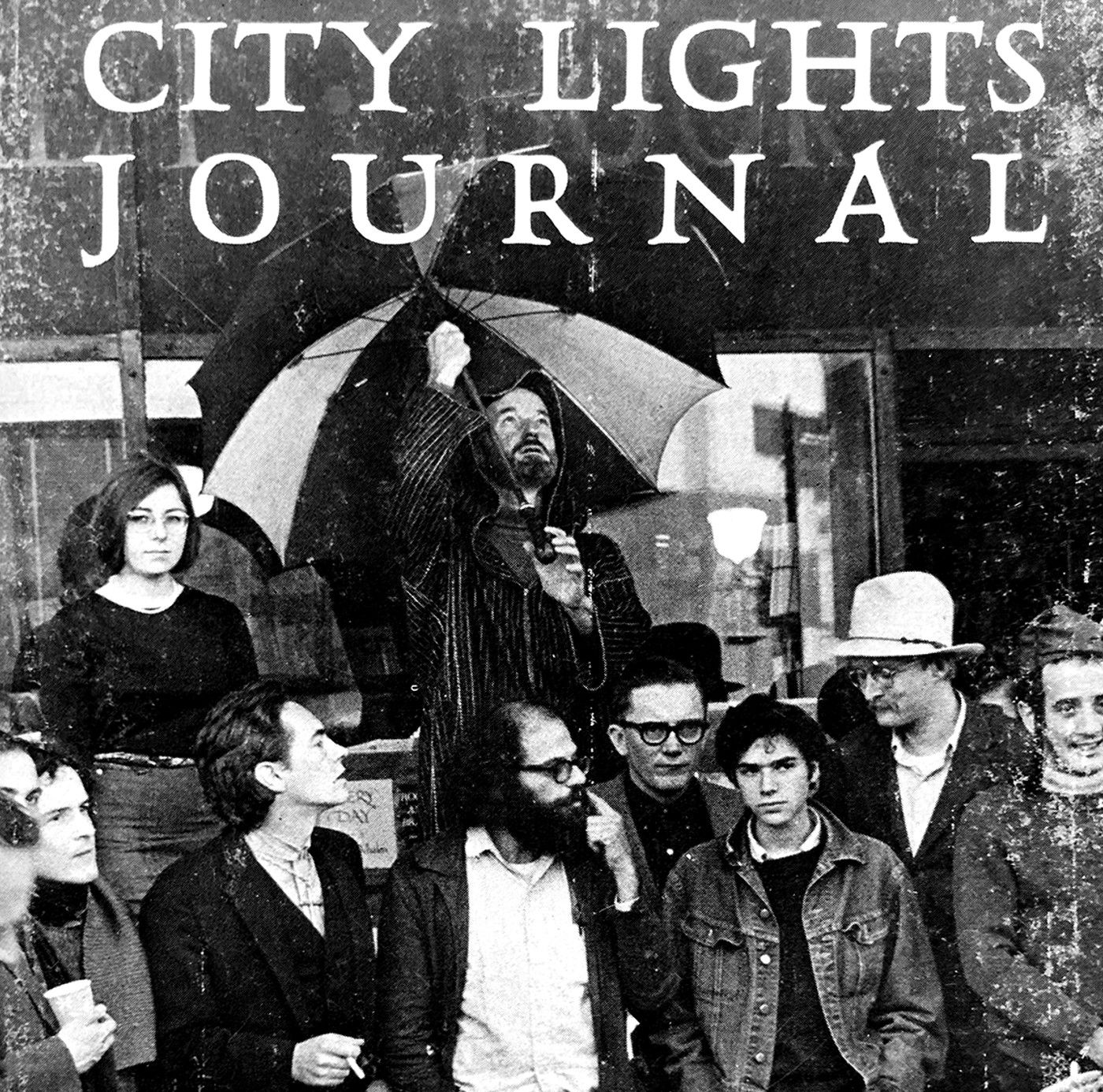

Alan Moore: But at the same time, if you do actually look up the iconic cover of City Lights Journal Number 3, where you’ve got a bunch of leading Beat figures standing outside City Lights Bookshop with Larry Ferlinghetti opening an umbrella, you will see between the actor and comedian Gary Goodrow, and the white Stetson-hatted Richard Brautigan, you will see the left ear and left side-parting of Harmon Belner.

This is sounding like another version of John Constantine writers meeting the character in the real world.

Alan Moore: Well, I was just looking at it and thought ‘oh, there’s somebody you can’t see, I’ll make that Harmon Belner, and then I’ll have him complain in the poem about how Richard Brautigan was blocking him. Nobody’s going to get it except for the couple people who do, who perhaps come across that photo and think, ‘yeah, let’s have a look… oooooh, there is an ear and a side-parting of an unidentified… I wonder if that could be Harmon Belner?’

Magic is real!

Alan Moore: Yeah! Yeah! It’s like I say, I like to put a lot of my stuff into the ambiguous zone between what’s real and what’s imaginary, and ‘American Light’ was a bit of an exercise in that.

One character you’ve written who might be considered a cautionary tale in treading too close to that zone is Snowy Vernall in the Jerusalem chapter ‘Eating Flowers.’ In terms of the danger of getting caught up in fantasy, what are you trying to say with that idea in Jerusalem?

Alan Moore: You have to remember that most of Jerusalem actually happened. I mean, it’s the story of my family, although I have been liberal and made up some things. But, basically, Snowy Vernall was my great-grandfather on my father’s side. His name was Ginger Vernon, and Ginger Vernon would climb up sheer walls to admire a bit of nice chimney breasts, or to harangue the crowds in the street below, which he did. There’s a Chronicle and Echo clipping from the ’20s or ’30s about him being taken to court for being drunk and on top of a building shouting at the crowd.

With the whole of Jerusalem, I was taking my somewhat odd family history and applying it to this idea of a block universe, as proposed by Albert Einstein. That we are in a block universe, a solid block of four-dimensional spacetime that is unchanging and is eternal. You can extrapolate from that to say that if that big block of spacetime is unchanging and eternal, then everything in it is unchanging and eternal, including us, including the empty beer can in the gutter. Everything is eternal. I suspect that people will perhaps catch up with this idea soon, and what it means. I was seeing something from an American science magazine saying ‘is death an illusion?’ And, yes, sort of. I think maybe 10 or 15 years ago I clearly stated it, that death is a perspective illusion of the third dimension, don’t worry. I said that somewhere in Promethea. So, I wanted to actually think, ‘alright, if that was true, and if there had been, say, a couple of members of my family who had perhaps had direct experience of that…’ because, yeah, there was also a reported madness in the Vernon family. Which I think was a tad unfair. I think Ginger Vernon was apparently a very talented man. He probably had mental issues. He was perhaps bipolar, something like that. He had terrible rages, apparently. Smash up everything in the house.

As for the other person in the Vernon side of the family who was committed, that would’ve been Audrey Vernon, who becomes Audrey Vernall in Jerusalem, who, as it turns out, had got quite good reasons to have a breakdown. But, I was imposing that eternalist block universe view onto the history of my family to see what happened. I had heard that Ginger Vernon was a fresco artist, that much was true. I’d also heard, and I couldn’t verify this, but I’d heard that a previous member of the family had also been a fresco artist and had helped with the redecoration of St. Paul’s. So, I decided to make this unknown ancestor into the first person in the family to actually have contact with this timeless reality when he’s repainting the angel’s faces inside the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Yeah, in Jerusalem‘s ‘A Host of Angles.’ The prose is very structured and fine in that chapter, but then after that moment, everything starts spinning out of control throughout the rest of the book.

Alan Moore: I suppose, I was trying to make the prose different in all of the chapters, certainly in all of the chapters of the last book of Jerusalem. With that, I wanted to actually give a first-hand account of what that consciousness might be like, and what it would do to your life and to your perceptions. I suppose that I was, on a simple level, I was trying to come up with a fantastical excuse for my great-grandfather being a psychologically unbalanced alcoholic, of exceptional talent it must be said. I thought, ‘what if you actually did see the world where the future was already written, could not be changed, and the past was what it was, where you actually knew that this life was forever? What would that be like? Would you perhaps take greater physical risks, knowing that they weren’t actually any harm to you, because that wasn’t how you were going to die?’ And I conflated a couple of stories about Ginger. I mean, I know that he did once at the end of his life start to eat a bowl of flowers, and I know that also towards the end of his life he became confused when he was in my paternal grandmother’s living room because she had mirrors hanging on either side of the room, and he thought that they were windows, and that he was looking into all the other houses in the row where there were other old men. Of course, it was him, but he thought that these were his neighbors. ‘Oh, there’s old Charlie from two doors down.’

So, I kind of wrapped all them up together into his death scene, where I actually have him choking on the flowers rather than just eating him. These are the little bits of ‘ah, yeah, the story didn’t happen exactly like that’… but my brother did choke upon a cough sweet, turned blue and had to be taken in a vegetable delivery lorry on a journey. He’d stopped breathing. The journey, even at the fastest speed, it would’ve taken ten minutes. So, that was one of the inspirations for Jerusalem, I thought ‘right, that ten minutes when he was technically kind of dead, I can expand that by the writer’s art into a massive adventure in the otherworld.’ Jerusalem was applying a fantastic overview and perspective to my ordinary family history and then seeing where it took me.

Alan Moore on His Northampton Epic, Jerusalem

Let me ask you about Book 2 of Jerusalem, ‘Mansoul,’ because it was such a surprise. You begin Jerusalem with a bit of mystique, playing with the idea that it will be very similar to Voice of the Fire, but with the family elements thrown in, however, “Mansoul” reveals this whole plucky children’s book narrative inspired by Halloween Tree and House with a Clock in Its Walls.

Alan Moore: I’d had a desire for some years to – I thought, ‘you know, I really ought to write children’s fiction.’ And then, with the Harry Potter thing, I tended to think, ‘Nooooo. If you do it now, it’ll just look like you’re eager for big bit of this lucrative children’s market.

There are still things about the children’s book that I kind of like, so I thought, ‘why not basically make the middle section of Jerusalem, where you’re going to be dealing with the otherworld, with Mansoul, why not make that like a savage, hallucinating Peaky Blinders?’ It’s about a group of children, so it’s got the vibe of all those kids’ gang stories, but they’re not actually children. They’re all dead for one thing, and some of them died when they were adults, but just remember themselves best as children. So, there’s adult material in there. It was also the only part of the book where the structure of the chapters is linear. This happens, then this happens, and then this happens and then this happens. The other two books are chapters that are not arranged in chronological order necessarily. They’re just placed where they are for other reasons. With that central bit, it’s got a fairly conventional linear structure. It’s about a gang of kids having fantastic adventures in this fourth dimensional otherworld, and it was also progressing the plot of Jerusalem and saying more things that I wanted to say about all of that.

A lot of Jerusalem plays with the idea of what comprises a cohesive narrative in that way. You draw attention to the idea of someone reading a story without appreciating their own role in it, because of their own misconceptions of what it could or should mean.

Alan Moore: I mean, I have had a couple of reported cases of Jerusalem fever, which is where people get to the end of Jerusalem and can’t think what to read next, and so start reading Jerusalem again. I know one woman who claims to have read it about seven times, which I would’ve thought life was too short for. But it’s rewarding to know that there is enough in there that you can go through it seven times and still find things that you’ve missed, so that’s good.

You’ve got a poetic use of prose that makes it the quickest, breeziest Bible-length read imaginable.

Alan Moore: Well, thank you. A lot of that is the rhythm with which I write. I am obsessed with rhythm, because it will create a rhythm in the reader’s head. And if that rhythm is smooth, then they will absorb the prose without little stumbles or things like that. It’ll be easier for them. I think that’s perhaps one of the things that – of course the use of language as well, but the rhythm I think is one of the things that gives the poetry some room to breathe.

There’s also a clarity to your psychological insight that’s very conducive to that. For example, in ‘And, at the Last, Just to Be Done with Silence,’ where you have these two characters wandering around medieval England in your classic horror style.

Alan Moore: That was a story I’d thought about when I was doing the research for Big Numbers in 1986 or 7 or whatever it was. I had come across this story about these people, some sheriff’s men, who’d gone into a church in Brackley, and dragged out somebody who was taking sanctuary there and hung him. And because of the power of the church in those days, they themselves had been punished by having to pick him up and carry him on their bare shoulders around every church in the parish where they would be whipped. I was thinking, you’d be mad wouldn’t you? If you’ve got bare shoulders that have been whipped, so you’ve got open wounds on your shoulders, and you’re carrying a decomposing corpse, you’re going to get all sorts of blood poisoning.

I’d heard that people like St. John the Divine, and some of the early Christian mystics, it would’ve been as a result of scourging that they had their visions. That, with uncured leather they’re flailing their backs, and they’re getting ill, and they’re having fever dreams. So, I thought, ‘well, there’s probably a story there,’ but it took me 30, 40 years to actually get around to doing it. But when I did, I just thought, ‘well, let’s just do this as dialogue. Let’s just do this with just somebody speaking, somebody answering them, and so on.’ This story that I’m thinking of, you couldn’t do it in a film, you couldn’t do it in a stage play, you could do it as a radio drama. In fact, when they asked me to read that story for the audiobook, I thought ‘oh, that might be quite difficult. I’m going to have to do two different voices, aren’t I? Two different voices in conversation with each.’

Alan Moore: Yeah, I did the voices myself. I’ve got one of them, the one of them who’s actually silent to begin with, he’s got a low, gravelly, kind of pissed-off sounding voice, and the other one’s got a more high and foolish sounding voice. Perhaps slightly influenced by the Fool in King Lear, because the scene where King Lear is wandering around, sort of [in a] psychotic state, and has only got his fool for company, people have pointed out that the Fool disappears. That the Fool is not mentioned before Lear enters his psychotic state and disappears immediately that he is found by other people. It’s as if Shakespeare were saying that the Fool wasn’t actually there.

So, you’ve got this apparent conversation between two men who have both been involved with the dragging out of a man from sanctuary in Brackley and with the punishment that came after that. I thought that would make a good, little story, perhaps five or six pages, and that will be plenty. Just get the readers thinking one thing and then sort of reveal that, no, it’s actually much, much worse than that. I was pleased with that, I’m not going to say it wasn’t a lot of fun doing the audiobook version.

And it’s also sort of a throwback to the Francis Tresham chapter in Voice of the Fire, ‘Confessions of a Mask.’

Alan Moore: Oh yeah, ‘The Confessions of a Mask.’ That’s one that I’ve done when I’ve read stories from Voice of the Fire in public. It’s one of the shortest ones in there, but it’s also one of the bleakly funniest ones.

They’re all very bleakly funny.

Alan Moore: In fact, the Francis Tresham one – it’s about halfway through the book, and I’d thought, (soberly) ‘Jesus Christ, these stories are really bleak. In the first one you’ve got this child who’s ritually murdered and then in the second one you’ve got this, kind of, Bronze Age psychopath and so on and so on.’ I thought, ‘perhaps I could do with some humor at this point. I’ll put a funny chapter in that will lighten it.’ And then I realized that ‘your “funny” chapter is a severed head on a spike having a miserable time of it.’ Yeah, so perhaps my ideas of what is a bit of light relief don’t really coincide with anybody else’s.

He got a new friend, though.

Alan Moore: He did, yes, with Captain Pouch. Again, all of this stuff is based upon life. Francis Tresham did end up on a spike at the end of Sheep Street, and Captain Pouch, who was put there for standing up against the enclosures, when the nobility were just going out and grabbing all of the common land. In this case it had been the Tresham family that had been grabbing land, and so, I thought, ‘oh, that would be an awkward conversation, if you ended up on the next spike.’ There was about an 18-month gap between them going up there, but I thought, ‘well, they could’ve left his head up for an extra 18 months.’ This is one of those things why I’ve written so much stuff about Northampton. I’ve very seldom had to make anything up.

Like the “brave” crusader knight you invented for ‘Limping to Jerusalem.’

Alan Moore: I didn’t invent him, no, he was real as well. Simon de Senlis.

You brought him to life, though.

Alan Moore: I suppose I did invent him. But, it’s like, if I invent people from enough basic hints – it’s totally unfair and delusional, but I like to think, ‘yeah, that is definitely what the real person would’ve been like.’ No, I know that it’s not. I seriously doubt that [From Hell’s] William Withey Gull for example was actually the White Chapel murderer, it’s just that that was the best story for my purposes. No, I do quite like those acts of ventriloquism, speaking in different voices. I have heard somebody else saying that Voice of the Fire was a polyphonic novel, it’s got many voices, and they’re spread across time. And I’ve heard book reviewers talking about other books saying that ‘yeah, actually this is a book that has chapters spread across time and numerous voices in it,’ and pointing out that there weren’t a lot of these books around before Voice of the Fire, which didn’t get a huge reception, but I think was possibly influential.

What was it like creating the voice of your friend, actor Robert Goodman, for the Jerusalem chapter ‘The Rood in the Wall’?

Alan Moore: I know that Bob, as I call him – he insists upon Robert Goodman, so I just call him “Bob” just to annoy him – I know he was quite apprehensive about that chapter when I told him that I was going to include him as a travestied figure of fun in Jerusalem. But when he read it, he thought it was quite funny as well. He probably thought it made him look quite noble.

Alan Moore Fixes Popular Entertainment

Finally, you’ve talked before about what you see as a decline in popular entertainment. I was wondering – given your experience with small press or self-published magazines – if you think part of the problem lies in how to produce and distribute good stories.

Alan Moore: I’m just so used to dealing with the world as it comes that the situation that I started out in was one of climbing from precarious rung to precarious rung. I got a little three-panel, four-panel comic strip in a short-lived local alternative paper, a community newspaper, that wasn’t any good at all. But when some people in Oxford were starting a community newspaper, an underground paper, called The Back Street Bugle, we had friends in common who thought to ask me if I could provide a strip for them. I then went to the music press that existed at the time, sold a couple of illustrations to the New Musical Express, and then landed a regular weekly strip at Sounds, which was probably a poor relation to the NME, but had its virtues. I’d been working in comics fanzines, underground papers, local newspapers, music papers, so these were the precarious rungs that I climbed into the then-existent world of comics, where, if you were lucky, you would start out doing very short throwaway strips on an occasional basis for something like Doctor Who Weekly or perhaps 2000 A.D. So, that was where I learned my craft, doing these occasional four-page stories, and short stories are still the best place to learn. And yet, most of the people from my generation would tell you different but similar stories of how they managed to get a career as a writer or as an artist.

The thing is that those rungs, as precarious as they were, don’t exist anymore. There aren’t underground papers, there aren’t fanzines, there aren’t music papers, there aren’t even local papers. So, when people ask me how to go about a career as a writer or an artist, I have to tell them that I really don’t know. I don’t know anymore. Everything seems to have been streamlined, and I’m not sure that that is producing better creators. For example, if you want to get into writing comics these days, the first thing that you’ll probably be doing, it won’t be short stories because there’d be no short stories in comics anymore. You’d probably be given a series, or a graphic novel maybe and you’ll have had no time to actually learn your craft, but, straightaway, you’ll perhaps be making a lot of money for a franchise character, or a former franchise character. I don’t see the values in stories actually improving much.

There are some fantastic stories available in literature, in some films, in some TV series. There are some very good writers in some TV series. But overall, I think everything is tending to get a bit formulaic. That it’s the people who control the various media that actually get these works of art to the public who very often, at least in comics, actually seem to be frustrated artists and writers. Who will, in the comics industry, from what I understood – for a long time it had been the policy for whoever is running the company will be essentially coming up with the way that they want all of the storylines to go for the next year. They’re not actually trusting the writers to actually write, and probably in some cases they’re quite right to do that. They’re not trusting anybody to actually have creative input of their own, to have a vision that they want to see through, and I can’t help but feel that the arts themselves will suffer for that, and also the people who could have got into the arts, and who could have reinvigorated it with their ideas, they’re not going to be able to do that.

So, what would be a better situation? I’d like maybe a return to some of the older forms of culture, because, just because they have been apparently superseded, that doesn’t mean that they’re banished, or that there’s no point to them anymore. When the camera was invented, all of the painters in Europe didn’t immediately go out and burn their easels and brushes. There is still painting, even if we have a more high-tech way of producing images. And it’s the same with stories and with culture in general, that, yes, the whole world, we are told, is destined to be run completely online. I wasn’t consulted. An awful lot of the people that I know weren’t consulted, obviously, and that really doesn’t work for me. If it works for other people? Fine, although I’m not sure that it does. Given the immense amounts of political instability that have been occasioned by online interference, firms like Cambridge Analytica, and all of these other movers and shakers who have been targeting different voter groups and stuff like that. Who were responsible, it was found out by the electoral commission over here, for completely throwing the results of the EU Referendum in 2016, and who weren’t a million miles away from the people organizing Donald Trump’s campaign a few months later that same year. This online world has got a lot of problems with it, but one of those is that it’s made people think that other forms of expression are kind of old-fashioned.

I’d like to see a return to physical culture. I’d like to see a return to music papers and physical fanzines. I’d like to see – I mean, the hippy culture that I grew out of and the culture that Beat culture turned into was entirely – the actual texture of it, the fabric of it, was hundreds and hundreds of cheaply produced poetry fanzines. Little poetry magazines, which I spent quite a great deal of money on buying in the moment. Things that were originally 50 cents that had got brilliant poems in, by poets who went on to become really famous or really accomplished. These artifacts have got so much of that era in them, and offer so many possibilities. When I was producing things like my crappy school poetry magazine, Embryo, and the Arts Lab magazines, we were doing them all upon a big duplicator where you had to type them onto wax stencil, then put the stencil physically on the drum of the duplicator machine, turn a big handle that would propel single sheets of paper through the drum, which would come out printed on one side. So, it took quite a while to print and staple even 200 copies of a twenty-page poetry magazine, but that physical culture, it was important. And at that time, we would’ve killed to have the possibilities that desktop publishing offers. What kind of Arts Lab could we have made if we’d have had the technology that is around today? What kind of magazines could we have published? What would our music have been like if we’d got that facility for it?

And yet, now that that technology and that capability is within everybody’s grasp, when anybody could produce a magazine much, much better looking, much better presented than anything we did in the Arts Lab on their desktop computer, nobody’s doing it. There aren’t poetry magazines. There probably are, but nowhere near the number that there were. There aren’t fanzines. There aren’t any places where people can try out their work and get themselves published. So, I would say, that an ideal situation for me was, if we took, in some areas, a couple of steps back. Or at least, if part of the culture took a couple of steps back.

For one thing, I think that if we had more of a material culture that produced artifacts, we’d perhaps be able to have a counterculture again. We haven’t had a counterculture really since 1990. We had Britpop which was imposed from above and was just basically a recycling of English guitar music in the 1960s and 1970s. A bit of Beatles here, a bit of Kinks there, a bit of David Bowie. It was nothing new, it was a fake counterculture, instead of the countercultures and youth movements that preceded that. And I think that that is because countercultures are a bit like snowdrops or something. They need a particle, some sort of airborne pollutant to coalesce around. They need something physical to coalesce around. So, I’d say I’d love a bit more material culture. I don’t think that the future of everything being online sounds particularly attractive to me, or particularly stable. Yes, I know a physical book won’t last forever, but it will last quite a long time, and it will have – a physical book, yes, you could get it on Kindle, and it wouldn’t take up half so much shelf space, and yes, I am saying this to you from a room that is full of books piled upon books and I don’t know where any of them are, not ever.

These books, I can remember where I got most of them. I can remember what I was doing that year, what the flavor of that year was just from looking at the cover illustration, at all of these little things that were part of the physical universe that gave it so much of its texture. Obviously, there are some things that work a lot better when handled online, I’m sure there are, but I don’t think that we should actually suddenly decide that the entire physical world is obsolete before we’ve actually thought that through. So, yeah, a return to some sort of material culture, even if that’s augmented by the technology of present day and the future. I can’t help but feel that a physical culture would be something that I think would be a lot more sustainable. It would probably allow a lot more people the opportunity to see what they could do as an artist, as a writer, as a musician or whatever. I think it would probably be a bit more democratic, and perhaps a bit more enjoyable, but that may be just me.

Alan Moore‘s Illuminations is currently on sale from Bloomsbury Publishing.