By most accounts, The Holdovers is a future classic and yet another success from director Alexander Payne. Payne also directed 2014’s Nebraska and won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for his 2005 hit Sideways. On his latest film, Payne reunites with Sideways star Paul Giamatti, who has been praised in many a The Holdovers review for turning in yet another fantastic performance.

Another returning collaborator of Alexander Payne’s is Mark Orton, a composer and multi-instrumentalist who previously scored Nebraska. Orton is an incredibly versatile composer, having written music for bands, podcasts, concert orchestras, and more; on The Holdovers, Orton takes an organic approach that makes it easy for audiences to put themselves in the heart of the story. Orton also leaned into the film’s 1970s setting, creating musical tapestries that reflected some of the popular songs of the era.

Mark Orton spoke with Screen Rant about his instrumentation choices, collaborating with Alexander Payne, and more. Note: This interview was conducted during the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike, and the movie covered here would not exist without the labor of the actors in that union. This interview has also been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Mark Orton On The Holdovers

Screen Rant: That’s quite a collection of stringed instruments.

Mark Orton: Yeah. This is where I do like 90% of it. I’ve got a cimbalom hidden under a desktop, and then a lot of the bells that you heard on the score. Then I’ve got old pump organs, pianos, guitars, and a lot of antiquey stuff that I repurpose for the textural side of things.

Do you try to play as much yourself as possible?

Mark Orton: It’s yes and no. I came at film scoring generally sideways. I had a group; a sort of fine arts center ensemble. It was crossing over between avant-garde jazz and modern classical music. That group used to tour, we did stuff for Blue Note, and we were on EMI. This is this thing called Tin Hat Trio that later became Tin Hat. That music was getting licensed into film a lot.

The reason I say sideways is I never went to film scoring school or poured coffee for Hans Zimmer or whatever. I didn’t do one of the more typical routes in. I honestly used to just have this multifaceted career where I would do stuff for a dance company, or I was doing touring work and releasing records with my weird band, and then I was doing stuff for This American Life, and then I was doing an occasional film and score.

I also inadvertently had the requisite skillset for a film composer because I have an orchestral background. My dad’s a conductor, and I went to conservatories and all that. I also have a serious tech background, which is really important for the whole film composing world. I was an engineer; I used to run The Knitting Factory in New York. I toured with a lot of those bands; Zele and Zorn and The Lounge Lizards and that kind of stuff.

So, I just had the requisite skills. I also burned out on touring, and so film scoring was a great way to stay home. To your question, that sound came from a performance project for me, so yeah, it became a performative thing for me. And I love writing music on commission for a string quartet or an orchestra or something, but at the same time–and especially working with someone like Alexander Payne–I do go after a more organic and handmade approach to things on my film scores, and that’s the side of my work that he’s drawn to.

This is set in 1970. You collect these instruments, but how deep did you go in replicating or touching on that sound? Did you record anything to tape?

Mark Orton: It’s a great era for all kinds of people like me who are into vintage and retro gear on both sides of the recording console. My Les Paul guitars, my Fender Telecasters, my Fender amps; they’re all from that era. Those are the sounds that you’re going after. And likewise, I mix analog, which is a little bit insane. That’s also an old school thing. I don’t mix digitally in Pro Tools; I always bring stuff out through a console, and I’ve got a custom tube console that is good at vintage-y tones. A lot of outboard gear, some of my Neve stuff, my Telefunken stuff… that’s all from the late ‘60s or early ‘70s anyway, so that sound is already built into the studio

But then, on a more personal note, in 1970 I was two years old, so it’s not like it was exactly resonating with me in the moment. But as much as I had a conductor father and was certainly immersed in music with him throughout my life, I also had a brother who was 10 years older who I really looked up to when I was a little kid. I started playing guitar at four years old, so that was ’72, and the thing I coveted more than anything was my brother’s record collection. It had all of that ‘70s stuff in it. For a couple different reasons, this film has a deep nostalgia for me in going after this music. This is stuff that feels very primal to me as a composer in a great way.

It’s rare for me, also. I don’t often get to pull out a Les Paul in overdrive and an old amp and actually play, and that was really fun. And we did actually put together a band for this, and I did it at early stages. Very often in early stages of demoing cues, seeing if they’re going to work for your director, you’re going to be using MIDI, or using digital instruments to mock stuff up. They have to then use their imagination somewhat to get past those digital versions of things, and once it’s approved, you go in and you do a scoring session with a live ensemble. That’s really common. In this case, I decided not to do that. I actually used live instrumentation from the get-go, which is a financial risk because you’re spending a lot of money hiring good players and stuff.

I’m also a multi-instrumentalist, so it’s a little easier on me because I can play most of a rock band’s instrumentation on my own. I decided to go that route with it from the get-go, just so Alexander wasn’t forced to make a leap of faith with my MIDI digital drum sounds or whatever. I was able to go after those tones and that sound from the beginning.

I’ve seen a lot of things about scoring, whether it’s looking at old John Williams process videos or whatever, where the composer is very focused on hitting the right frame and hitting the right beat. It seems like that would be a lot harder to do with the method that you’re describing. Was that something you weren’t necessarily as focused on with this film?

Mark Orton: That’s a good question. Certainly, there are projects where that is exactly what I’m focused on. I think other than the analog mixing thing, another way that I’m different–and it does definitely come from the performative side–is that I don’t use click tracks. I’d rather it be that I’ve got some performative aspect going in, even if it is with a MIDI instrument, that’s establishing the time. In this case, it was a little bit more like getting a script and writing a suite or some overture based on themes early on, even before working with picture.

Alexander came up to Portland where I live. He spent a week with me, roughly, up here. It was us, honestly, not looking at picture, talking about the story somewhat, but really talking about the side of early ‘70s music he was drawn to, and what aligned with the film and the story versus what didn’t. There’s not early ‘70s funk or something like that in this score. We were discussing the stuff that resonated for him personally, so we were driving around and listening to Carol King’s Tapestry, or whatever. We were actually listening to music and talking about it.

I wrote a suite of songs early on, a third of which made it into the film, going after more particulars of the aesthetic. Then, of course, I did get the film, and I’d say that’s when a different hat comes on for me. I’m often taking material that I’ve already written more in the abstract, away from picture, and then as an arranger and my own editor, I’m going in and figuring out ways to have that match up with the action and follow character arcs, a general narrative arc, an emotional arc, or whatever.

I’ve seen this be called a holiday classic, which is very cool, but when you think of a holiday movie, you think of something more saccharine or a little more obvious. How conscious were you of wanting to touch on the setting and the time of year without going too far in any direction? Is that something you had to even think about really?

Mark Orton: It would be one of the first questions I would ask. I know Alexander’s filmmaking first as a fan, but also working with him on Nebraska and knowing him personally as well. [I know him] well enough to know that he’s not going to be looking for stuff that is super on the nose, but it’s going to be acknowledged. I did go out and buy… I had one or two, and now I’ve got 20 different sleigh bells from different eras that did find their way into the more comedic side, mostly, of the scoring.

[But] the music is not going to be leading the comedy, or the emotion, or drama. It’s going to be allowing for it and not betraying it. That’s not to say that Alexander is looking for this super-neutral score that doesn’t have any of those dynamics in it. It’s just that he doesn’t want to… music’s not meant to push or lead the audience, ever. It’s also walking that fine line with something like this because there are so many dimensions to the characters and story. It isn’t just some cookie-cutter Christmas film or something. There’s darkness and stuff hidden underneath the comedic moments, and the reverse is true as well, so I think the score has to reflect that.

You mentioned your brother, and I know you have some ties to the setting of the film. It’s shot on the East Coast, in Massachusetts. Compared to other projects you’ve done and worked on, how easy was it for you to connect to this on a personal, emotional level? And did that make it easier to score?

Yeah, it definitely did. It was a total random coincidence because Alexander didn’t even know that I had lived in this part of the world. I’ve lived in it three different times and seriously considered house hunting there before I settled in Portland, Oregon, on the other side of the country.

A lot of it is shot around Deerfield Academy, and I lived just a couple miles away in Sunderland, Mass. I love that part of the world; I particularly love winters there. I have some weird deep-rooted New England thing, and Western Mass was where it was at. I still love doing stuff back there, so when I’m getting to score a montage of them driving around in a car through those winter roads that I’ve literally driven in winter myself, it’s part of the world that I love and miss and romanticize.

My dad’s a conductor, so we’d go to Tanglewood or whatever. [There’s] MASS MoCA, Jacob’s Pillow… there’s an incredible art scene there. It’s this super deep-rooted nostalgia, [and] it makes it very easy to get at that if you have that kind of personal connection with it.

There’s one track from this that’s currently out on Spotify, “Into the Unknown”, which is gorgeous. Can you maybe talk about the significance of that track and why that’s the one that is out before the rest of the soundtrack?

Mark Orton: It was originally written, going back to what I was talking about, about nostalgia and driving those roads. The first iteration of that cue is a more spare and slightly more acoustic version, and then Into the Unknown is for a drive that happens at the very end of the film. That type of writing is a little more connected to what I did for Nebraska; they’re like songs without words. The music is kind of everywhere in this film. There’s chamber music with plucked strings and sleigh bells that is more tied to Christmas, there’s serious solo piano, and I use a lot of alto and bass flute, and there’s a boys’ choir at one point reiterating a theme from earlier.

But that piece in general, along with a couple others, is like a song without words. They’re the kind of songs that I write in my head, honestly. I do a lot of work in my head, but those, in particular, are going to be the things that I would sing into my iPhone or something as I’m traveling around. I think of it as traveling music in some ways, but also, it’s lyrical and singable and thematic. It’s also one of the main themes of the thing and it’s a more approachable one than putting out an alto and bass flute duet or something or a boys’ choir cue.

It is one of the main themes of the film, and both times it comes at small moments of redemption, or slight bits of resolve. There’s plenty unresolved, [but] there’s some hopeful in the melancholy in it.

About The Holdovers

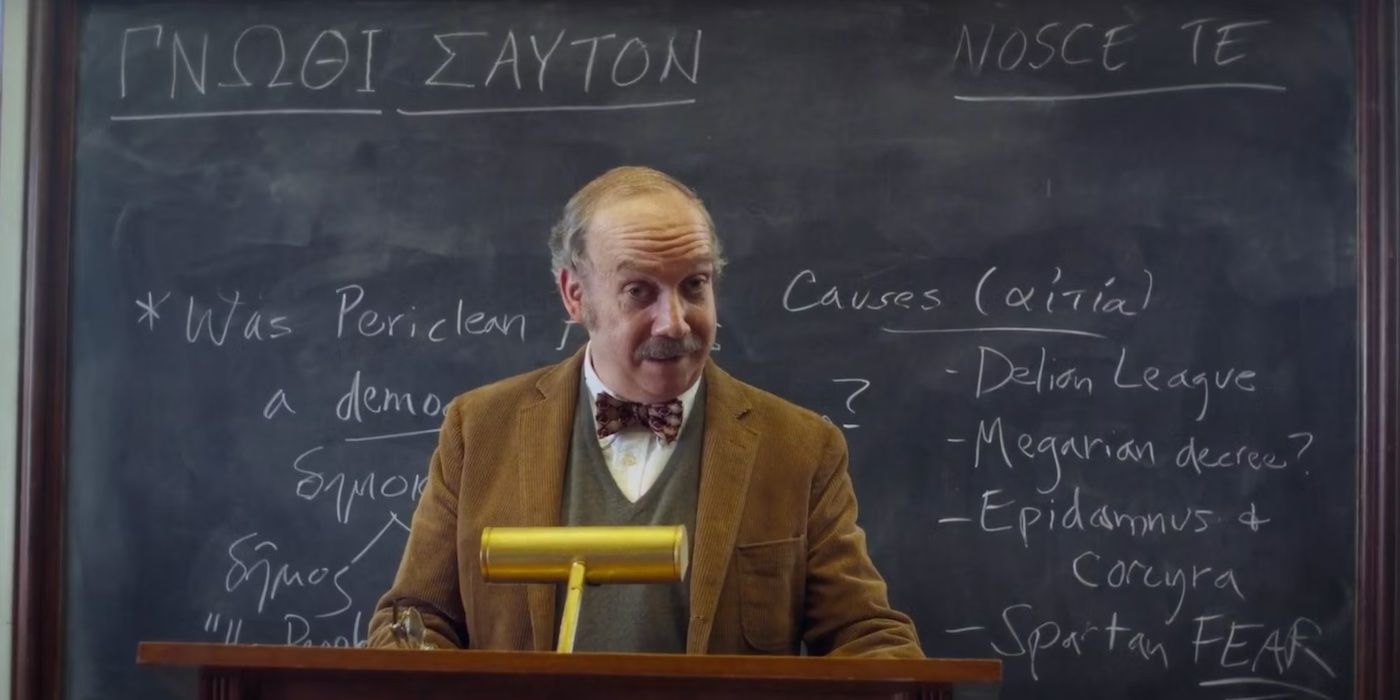

An instructor at a New England prep school stays on campus to babysit “the holdovers” –students with nowhere to go during the school’s Christmas break.

The Holdovers is in theaters now.

The Holdovers

- Release Date:

- 2023-11-10

- Director:

- Alexander Payne

- Cast:

- Paul Giamatti, Da’Vine Joy Randolph, Dominic Sessa, Carrie Preston

- Rating:

- R

- Runtime:

- 133 Minutes

- Genres:

- Comedy, Drama, Holiday

- Writers:

- David Hemingson

- Studio(s):

- MiraMax, Gran Via

- Distributor(s):

- Focus Features