Warning: This article contains spoilers for Superman: Space Age #1

Can a superhero ever truly be relatable to a real person? Debuting from DC Comics last week, Superman: Space Age #1, the first of a three-issue Elseworlds series focusing on a more classically tinged version of the Man of Steel, is one of the few stand-alone series of recent memory to try to tackle this all-important principle in the genre head-on. In doing so, it follows in the footsteps of, and in many ways directly revives, the spirit of some of its publisher’s most influential and genuinely innovative titles, namely Mark Waid and Alex Ross’s Revelation-inflected Kingdom Come and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ powerhouse fable Watchmen. The result, quite serendipitously, is that Mark Russell and Mike Allred manage to do the impossible and, through sheer heart, definitively capture that elusive spark that makes Superman human.

The genre of the superhero, now long one of the predominant popular fictions of the modern era, is not without its inherent flaws as a literary archetype. Tropes endemic to the genre, such as the heroes’ general moral infallibility, the repeated necessity to generate new villains on a rotating basis, as well as the general doom that hangs over their world due to the inherent cycle of escalating conflicts the heroes must go through, often leave the characters themselves lacking in certain, more everyday qualities. Common characteristics like basic moral uncertainty, lack of forethought for the consequences of their actions and genuine failure in the face of their obstacles, are nowhere to be found throughout much of the body of work comprising comic-dom, in part due to its longtime niche as children’s entertainment.

The issue also arises from the very fundamental concept of the superhero: obviously most superheroes have superpowers, and because of that, their characterization requires these heroic qualities to function, lest in the absence of them they prove to be more troublesome than heroic. And while this kind of story might prove suitable for a less-revered hero, Superman’s foundations of fighting for truth, justice and the American way leave little room for that kind of moral ambiguity in his depictions, with most alternate, less-than-pure Supermen being depicted as bad to the bone. Space Age refreshingly tells a different tale and brings with it a rarely resonant style of superhero storytelling.

A Fragile World

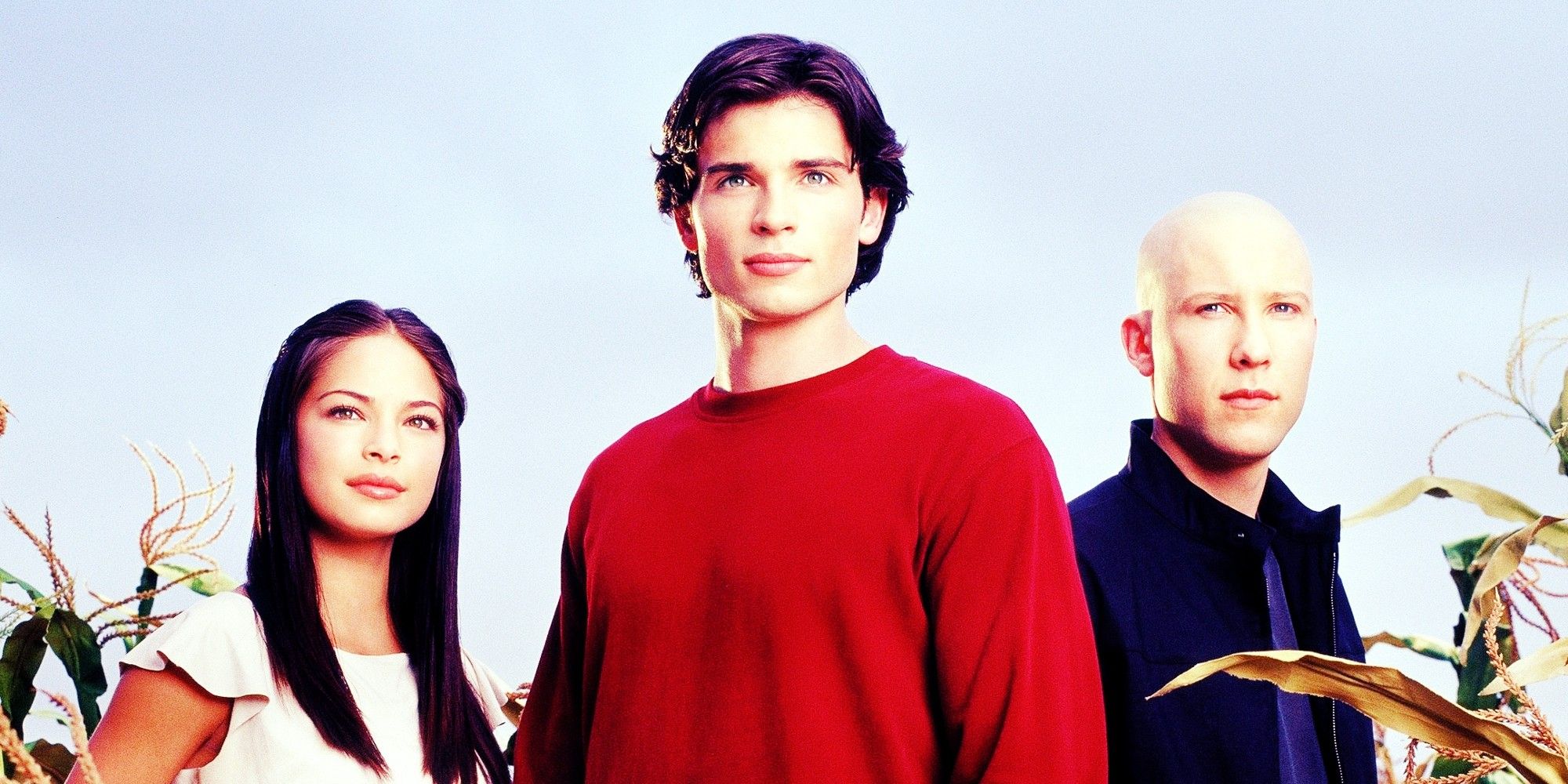

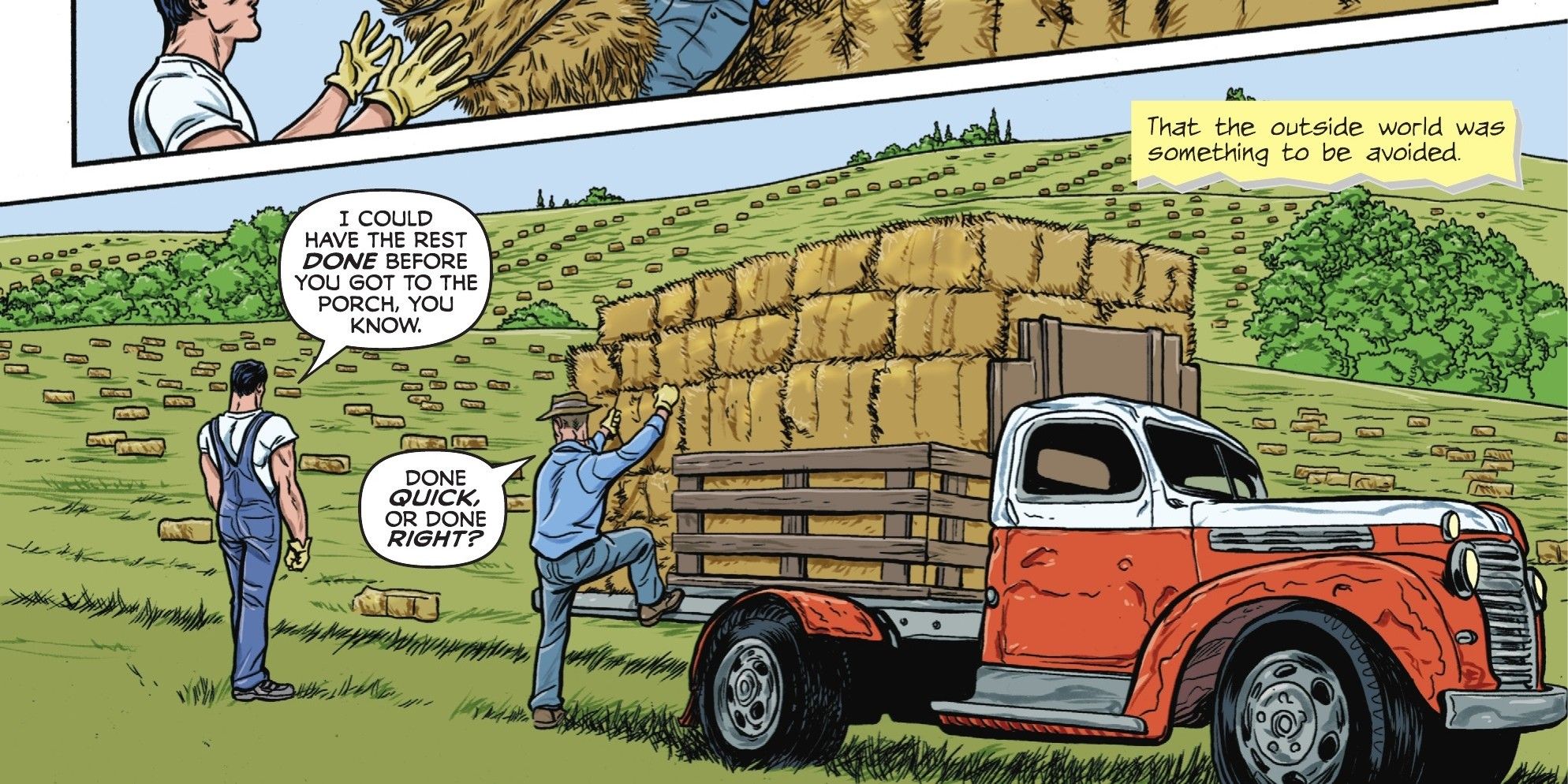

In Space Age, Russell crafts a young Clark Kent who, in what might be considered a reference to his film portrayals in Superman (1978) and Man of Steel (2013), is portrayed as reckless, somewhat bumbling actually, and seems to suffer from an inferiority complex, as if he feels he never quite manages to measure up to his ability. Growing up amidst the backdrop of Cold War Soviet tensions against his home country of the United States, Clark struggles in his youth to find the right ethical framework for his heroism, not really agreeing with his foster father Jonathan, yet not feeling adequate enough to live up to his father Jor-El’s teachings. He is a man in search of a code. Already powerful, and willing to use his powers to avert catastrophe, Clark inadvertently bites off more than he can chew during his first outing in 1963, when he almost ignites a conflict between the two rival superpowers simply by virtue of entering Soviet airspace, falsely believing a nuclear strike is imminent.

The scene echoes the themes found in 1996’s maxiseries Kingdom Come, known for its lavishly Rockwell-esque painted art by Ross, which stars an older Superman who returns after a long absence from public life to provide stability in a world overrun with highly destructive super-people. In many ways a commentary on the inevitability of destruction in a world populated by godlike beings, Kingdom Come often demonstrates the long-term effects of violence and fear among those who would place themselves as a bulwark against wanton mayhem. This Superman, a cynical if not well-intentioned totalitarian, inadvertently facilitates a nuclear holocaust during the throes of a violent conflict, leading to the deaths of the vast majority of metahumans in that timeline. The art by Alex Ross, regarded as some of his finest, imbues the story with an almost-Biblical aura, managing to produce a truly terrifyingly apocalyptic end to a world constantly on the brink of destruction, despite its relatively optimistic ending.

By portraying a Superman in a similar situation, yet without the mentality, experience or will needed to directly impact his greater socio-political framework (in this case the paranoia-laden specter of mutually assured destruction woven into the culture of the 1950s), Russell and Allred portray the hero in as fragile a light as can be imagined for so powerful a character. Allred’s art, a devastatingly immersive play on the famous innocent Silver Age aesthetic, grants this chaotic atmosphere a certain psychedelic twist reminiscent of Ross’ effect as it explores a Superman unsure of his own place in the battle against Armageddon.

Who Watches The Watchmen?

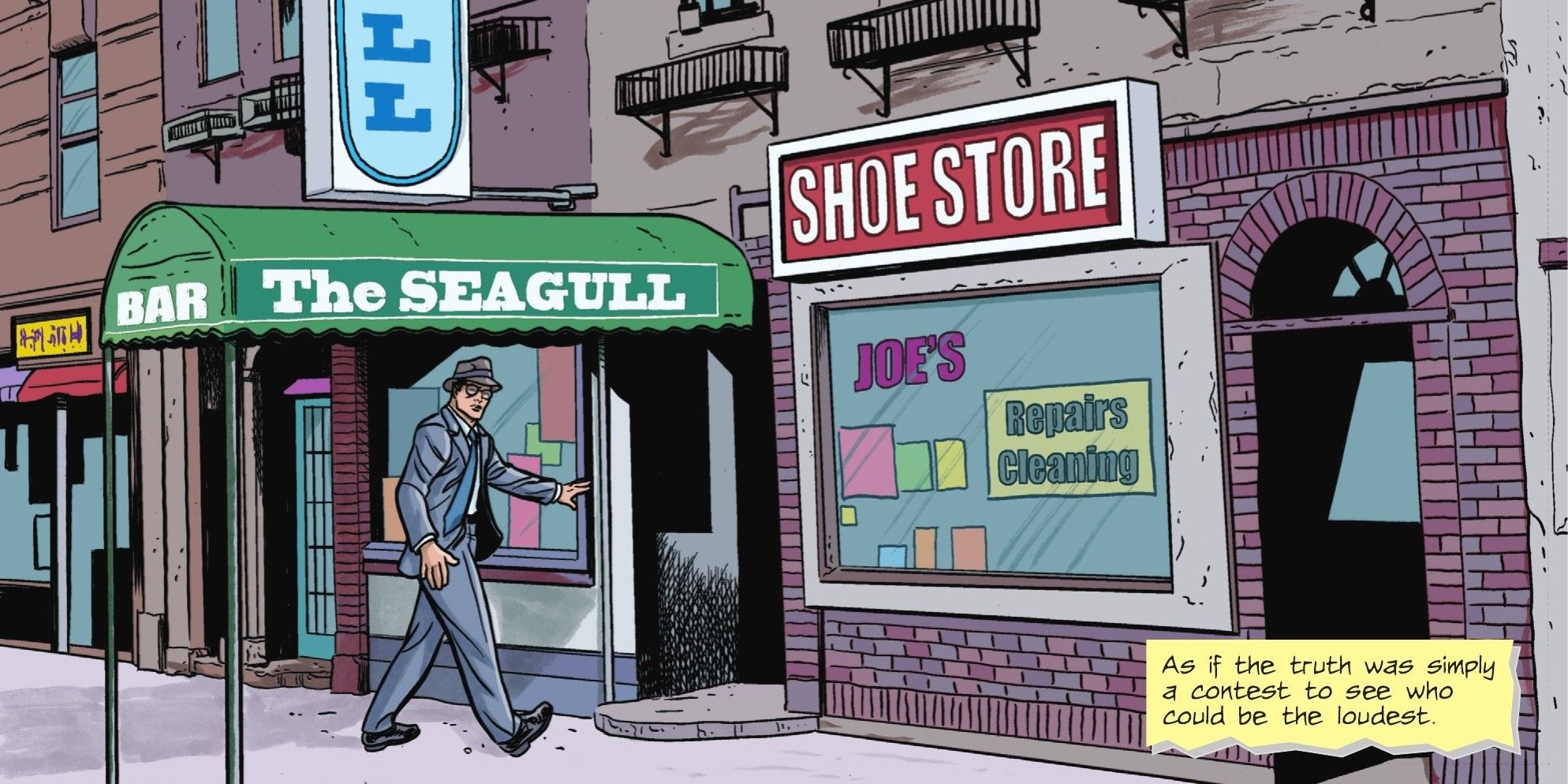

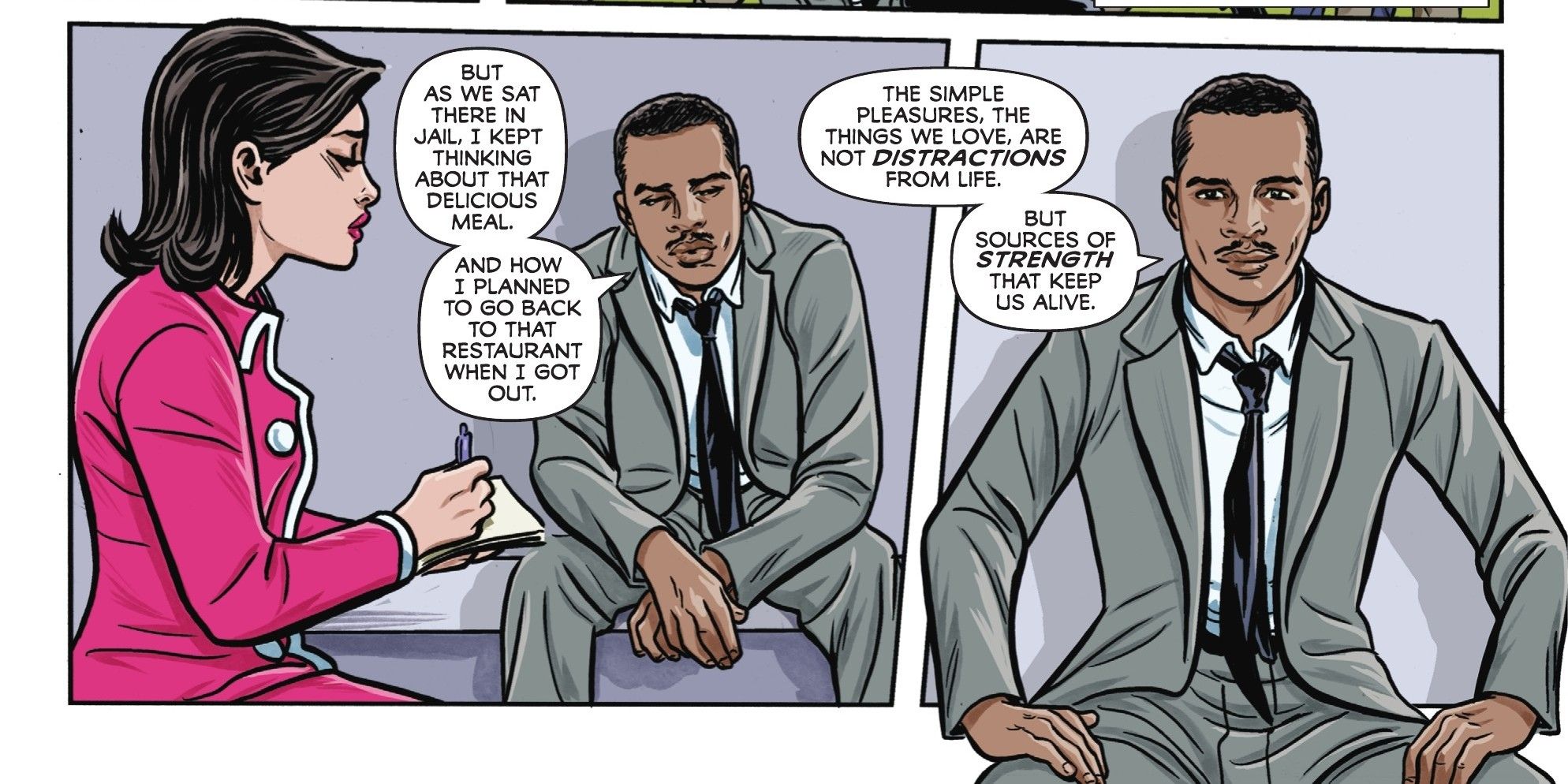

Superman: Space Age doesn’t just recast the more violent trends of the ‘80s/’90s comic stories as a logical conclusion to the Silver Age’s Cold War-influenced sense of moral futility in the face of annihilation that generated its stories. It also blends this ethos quite hearteningly with the sentiments of overt kindness, bravery and selflessness that pervaded the culture at the time. In its simple spinning of a world where superheroes arise in response to international and internal political conflict, Space Age recalls the seminal 1986 series Watchmen, but with a twist: all of the philosophical cynicism that Moore builds into his parable is instead turned inside-out in order to demonstrate an opposite, more empathetic side to its heroes.

In Watchmen, Moore imagines a realism-tinted world within a similar historically-set background, in which many of the former masked heroes, now pariahs following their legal necessity to register with the government, are shown to suffer from consequences of apathy, psychosis and rocky interpersonal relationships. Of particular note is the pairing of Dan Dreiberg (Nite Owl II) with Laurie Jupiter (Silk Spectre II), whose romance slowly burgeons over the course of the series despite their various hang-ups and lack of immediate chemistry.

While the vast majority of the relationships found in Watchmen are broken and off-track, Russell takes pains to breathe life into the good-natured, nurturing relationships in Clark’s life that help him find his way in this somewhat overwhelming environment he finds himself in. Not only does Space Age take pains to deliver a heartening father-son dynamic between Clark and Jonathan, it depicts his romance with Lois Lane in a mature, yet delicate fashion. Where Watchmen’s Dr. Manhattan is portrayed as being distant in his relationship with Laurie, an extension of his overarching passivity, Lois is instead a supportive friend and illuminative source of hope for the young hero, instrumental in his ultimate choice to take action and intervene in a nuclear doomsday scenario engineered by Lex Luthor between the two superpowers. In Space Age, Clark’s love of his friends and family stays his more drastic actions until this point, unlike Watchmen’s Rorschach, while imbuing patience in him to wait for the right circumstance to use his amazing powers.

Though only a third of the way through, Superman: Space Age reimagines Superman’s main internal dilemma as being a man of limited awareness who must try to take the burden of the world’s safety onto his shoulders. A story of a modern Atlas, what truly highlights this remarkable series is its human sense of delicate fragility in a world of godlike heroes.