Since the 1960s, the ratio of feature films shot in black and white to those shot in color has tipped overwhelmingly toward the latter. Each subsequent decade has made monochromatic photography (whether on conventional emulsion film or in digital) more and more a niche enterprise.

In light of this, the decision by director Alexander Payne (The Descendants) to film his latest feature, Nebraska, in black and white is an especially interesting one. Sometimes, a movie seems to demand being shot without color (something that’s absolutely the case with Nebraska) – even in an era in which black and white has fallen out of fashion. Payne’s choice of color palette has left us thinking about other black and white movies produced in the modern era. Join Screen Rant as we explore 10 of our favorite contemporary movies made in black and white.

A note before proceeding: For the purposes of this article, we will consider the term “modern” or “contemporary” to mean “movies produced since 1980.” This is a broad mishandling of the term, but it narrows the field down to decades in which black and white filmmaking became especially sparse.

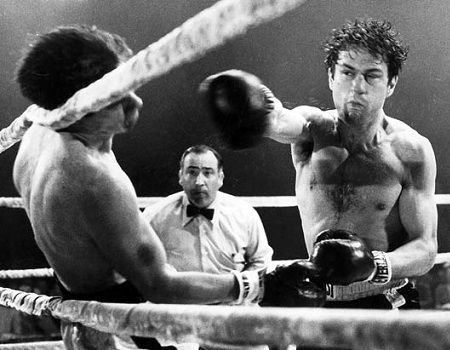

The all-time classic sports drama Raging Bull uses black and white photography to such spectacular effect that not including it on this list would be something of a travesty. Unlike many of the movies to come, Raging Bull was not the debut feature of an ambitious upstart – rather, it was the culmination of the partnership between director Martin Scorsese (The Wolf of Wall Street) and Robert De Niro (Grudge Match) begun years before.

Raging Bull tells the semi-true story of once-dominant boxer Jake La Motta, from his promising early life to his decline into a has-been riding the coattails of his earlier fame. Not only is the movie’s acting superb across the board, it may also be the most beautiful movie Scorsese has ever made. A combination of strategically deployed slow-motion effects and rich cinematography makes Raging Bull‘s boxing scenes some of the best (if not the best) ever filmed.

Director Jim Jarmusch (Only Lovers Left Alive) has shot extensively in black and white throughout his career. By the time he crafted the nightmarish postmodern Western Dead Man, Jarmusch had already shot in black and white for Stranger Than Paradise, Down by Law, and the first two segments of what would eventually be collected as Coffee and Cigarettes.

Almost two decades before he would play Tonto, Johnny Depp put on war paint as William Blake, a milquetoast accountant drawn into the violence and depravity of the frontier boomtown of Machine. When he takes a bullet while killing a local robber baron’s son, Depp flees on an increasingly strange and mystical journey through the wilderness.

Dead Man’s use of black and white photography accentuates both its connection to a genre gone out of style and the weird, dreamlike landscape of its narrative.

Most film careers don’t start with a massive, attention-grabbing bang. Such was the case with eventual Dark Knight heavyweight Christopher Nolan, whose first feature film was the quiet, anxiety-laden neo-noir Following.

Using tightly shot, murky cinematography and a broken narrative structure, Following concerns listless young writer Bill (Jeremy Theobald) as he gradually becomes obsessed with tailing random strangers in crowds. When one of Bill’s targets catches wind of the writer’s game, both are drawn into a spiraling game of thievery, intrigue, and murder.

Interestingly, there is little in Following to suggest that its director would go on to make the panoramic epics of Batman Begins or Inception. Instead, Following uses its close-up shots and shadow-laden cinematography to suggest an increasing claustrophobia – an effect that makes the film both tense and technically interesting.

The arty allure of black and white photography often appeals to young filmmakers out to make a name for themselves. For Kevin Smith (Tusk), shooting his debut feature without color helped give Clerks a low-fi, caught-on-a-security-camera feel that perfectly complements the story of a single day of retail hell.

Known largely for the no-holds-barred filthiness of its comedy, Clerks contains only hints of the Smith’s future status as an omnipresent figure in the geek community. A great part of the film’s appeal is in its listlessness – despite its wacky vignettes, Clerks captures the grim, vacuous feeling of a day ticking by behind a cash register. From that perspective, its washed-out palette makes absolute sense.

In yet another example of an eventual powerhouse auteur kicking off a career with a low-fi black and white film, Pi (technically not the actual title, which is the mathematical symbol itself) is a twisty thriller full of paranoia and pulsing dread. However, director Darren Aronofsky (Noah) goes the extra mile by immersing the audience into (as would become one of his signatures) what may or may not be a full-scale descent into madness.

Pi’s cinematography alternates between crisp, high-contrast shots and muddy shadows reminiscent of the most unnerving segments of Eraserhead. As the film follows its main character – a mathematician obsessed with discovering the universal secrets hidden in pi – into a labyrinth of conspiracies and hallucinatory encounters, the shot-work becomes as demented as its subject.

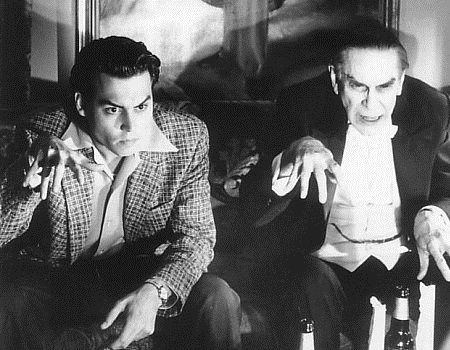

One of the most effective uses of black and white photography is in the evocation of another era. In the case of Ed Wood, Tim Burton (Big Eyes) shoots both in the medium and style of his subject, the legendary schlock filmmaker of the title.

Part biopic, part wistful dramedy, Ed Wood traces the “rise” of the titular director (played by perennial Burton collaborator Johnny Depp) and his unlikely friendship with ailing Dracula star Bela Lugosi. Their alliance leads to two of filmmaking’s most notoriously awful creations: Bride of the Monster and midnight movie mainstay Plan 9 from Outer Space.

Despite the notorious ridiculousness of the director, Ed Wood doesn’t treat its subject with contempt. If anything, Burton attempts to capture the same madcap enthusiasm (minus the ineptitude of Wood) in his filmmaking. In a way, the imitation is the perfect tribute to “The Worst Director Who Ever Lived.”

Sparking controversy almost immediately upon its release, Belgian mockumentary Man Bites Dog‘s almost casual depiction of violence and cruelty can make it a tough film to watch. At the same time, the movie is a razor-sharp satire of reality programming, documentary filmmaking, and society’s obsession with both celebrities and serial killers.

For a movie with such high-minded subtexts, Man Bites Dog has a bluntly simple premise: A crew of student documentarians follow Belgian serial killer Benoit as he embarks on a routine of larceny, sadism, and brutal murder. A charismatic narcissist, Benoit eventually convinces the slowly dwindling crew to take part in his reign of terror. Man Bites Dog‘s shot-on-a-dime style feels like the stylistic ancestor of currently popular “found footage” genre flicks.

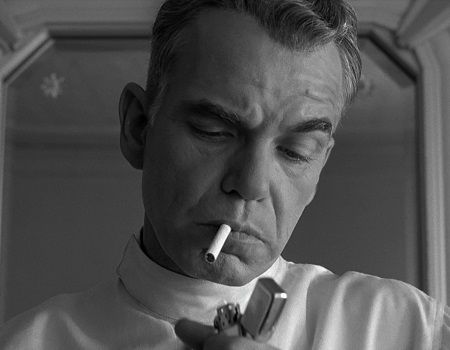

Often overlooked in the overall filmography of the wunderkind director/producer duo Joel and Ethan Coen (Inside Llewyn Davis), The Man Who Wasn’t There is a prime example of the pair’s prowess with genre pastiche.

A pitch-perfect recreation of the kind of noir films exemplified by Double Indemnity, The Man Who Wasn’t There follows an everyman barber whose ill-considered blackmail plot rapidly explodes out of control. If it weren’t for the contemporary actors and signature moments of boundary-pushing Coen weirdness, one might not be surprised to find out The Man Who Wasn’t There was released in 1949.

The real draw of the film is the cinematography by Roger Deakins (Skyfall). With shot-work so sharp it cuts the screen into a dazzlingly patchwork of light and shadow, The Man Who Wasn’t There displays all of the visual strengths of a black and white feature.

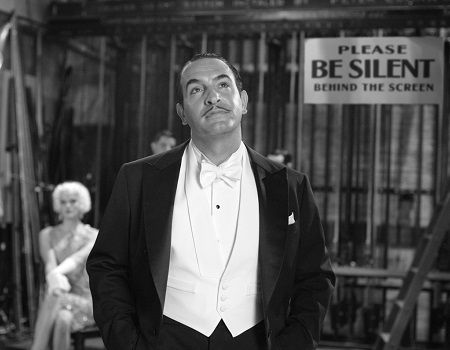

Like The Man Who Wasn’t There, Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist is a paean to another age of filmmaking – the Silent Era that reigned from film’s first tentative steps in the 1890s until The Jazz Singer ushered in the age of synchronized sound in 1927.

The Artist‘s style is fascinating, in that it seeks to emulate every quirk of the Hollywood era it depicts. From its madcap early moments to its exaggerated melodrama to an ending that introduces sound with a triumphant finality, The Artist reflects this period of transition on almost every stylistic level.

A great part of this lies in the movie’s skillful black and white cinematography, which manages to feel both modern and one of a kind with the sometimes-fuzzy shot-work of the late ’20s. It’s the key to a film that wants to immerse its audience fully in an era.

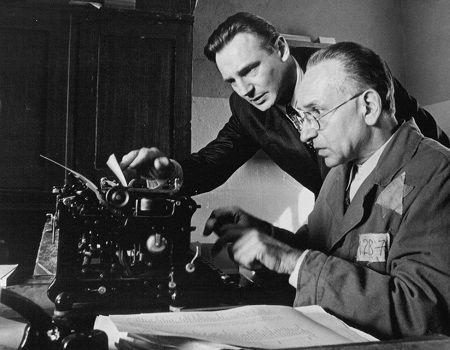

Yes, Schindler’s List is not exclusively a black and white film – there are flashes of red and a coda shot in color. Nonetheless, the majority of Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece of historical drama takes place in black and white, making it a fitting title to close out our list.

So much else about Schindler’s List has been categorized and praised to the rafters that we’ll focus solely on the movie’s stately monochrome cinematography, courtesy of frequent Spielberg collaborator Janusz Kaminski (Lincoln). Just as everyone involved in Schindler’s List is at the top of their game, Kaminski’s work as the movie’s director of photography sets the tone for every other element of the production. Using a combination of classically influenced compositions and skilled handheld work, Kaminski proved in Schindler’s List that black and white photography can be just as dynamic as color.

Honorable Mentions

Frances Ha (2012): A recent favorite of Screen Rant writers, Frances Ha uses black and white to complement a timeless story of youth in search of life’s purpose. A surprisingly fun, energetic flick about finding oneself.

Pleasantville (1998), Sin City (2005): Neither Sin City nor Pleasantville is strictly a black and white movie. Instead, both titles are worth mentioning because of the ways each plays with the mixture of color into a monochrome world – in order to accentuate a blunt social satire in Pleasantville, and to closely match the art style of Frank Miller in the case of Sin City.

The Mist (2009): A special case indeed, Frank Darabont’s The Mist was originally released in full color. However, one of the special features on its DVD release was a black and white version of the film that plays well to the tale of otherworldly horrors that arrive in an impenetrable fog.