Schmidt’s character development over seven seasons of New Girl highlights a problem in other modern sitcoms. Much like Friends and How I Met Your Mother, New Girl uses an apartment setting to explore the lives of a friendship group as they move from their twenties to their thirties. Schmidt’s journey on the show sees him go from an insecure narcissist in New Girl season 1 to a loving father and husband by season 7.

Until recently, sitcom characters have largely avoided the scrutiny that is leveled at characters in dramas. They haven’t always been required to show growth, and thus they remain unrealistically static in an effort to maintain authenticity. However, the increasing backlash around toxic masculinity in characters like Friends‘ Ross Geller means the sitcom genre has to adapt, and New Girl has spearheaded this charge.

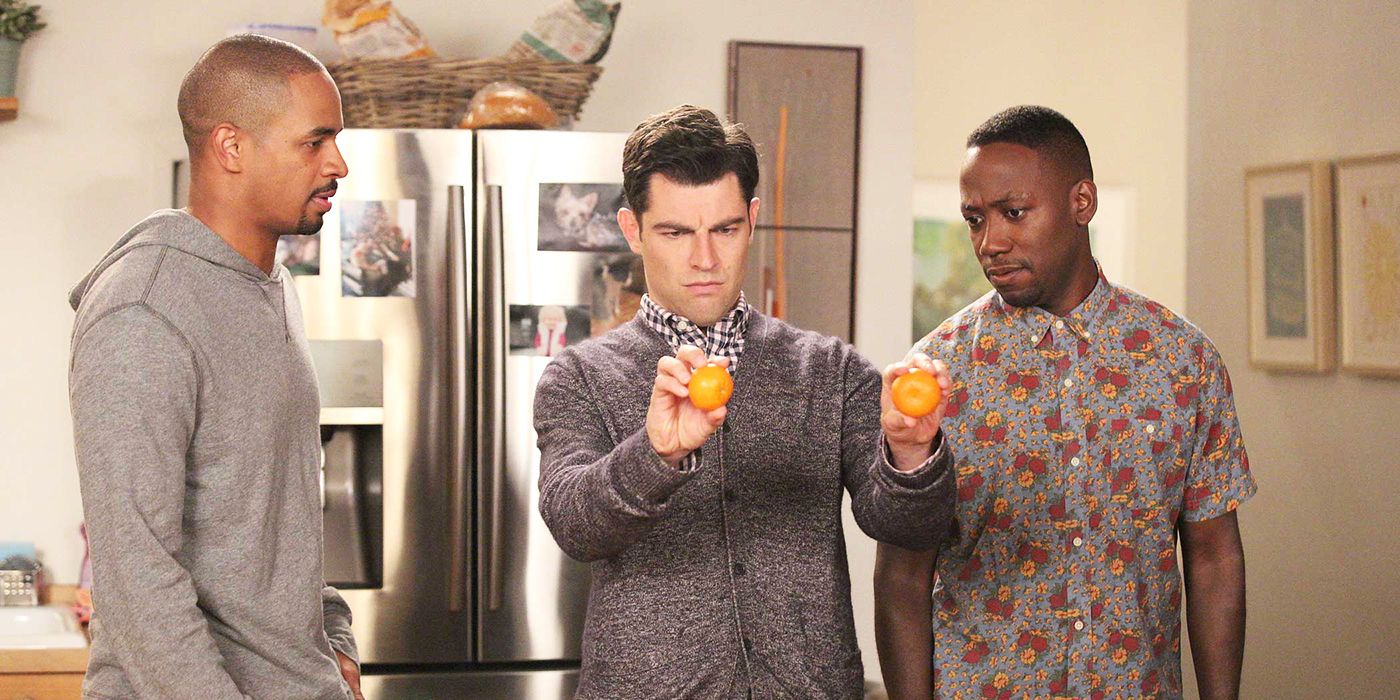

The lesson modern sitcoms can learn from New Girl’s Schmidt (played by Max Greenfield) is that a toxic character can evolve into a kind, empathetic human being without the need to sacrifice their defining personality. Schmidt’s organic growth proves that sitcoms that refuse to challenge the toxic behaviors of their characters on the grounds of consistency are actively condoning these behaviors. New Girl’s success has rendered this excuse unacceptable.

In New girl season 1, Schmidt is not dissimilar to Barney in How I Met Your Mother. The self-worth of both characters is dictated by delusions of power. They have well-paying jobs, take pride in their appearance, and boast of their sexual prowess. By New Girl season 7, Schmidt is a changed man, yet he retains the recognizable traits that made him likable in the first place: quirky mispronunciations; a hilarious obsession with his best-friend Nick; and a passion for the correct application of conditioner. Barney, on the other hand, remains self-obsessed and predatory throughout his sitcom. He is only forced to change when he becomes a father, which means he never had an earnest desire to outgrow his toxic behaviors. Sitcoms need to observe how the conclusion to Schmidt’s character arc still feels authentic to the version of the character introduced in season 1.

Importantly, New Girl never condones Schmidt’s toxic behavior. In season 1, episode 1, Schmidt is inappropriate towards Cece; he removes his shirt to flex his muscles and makes unacceptable comments. While this might get How I Met Your Mother’s Barney a high five, Schmidt is held accountable for his words and actions by way of a “Douchebag Jar.” Any time fault is found with Schmidt’s behavior, it costs him money. Importantly, Schmidt accepts his punishment; good-natured complaining aside, he never attempts to escape accountability. This shows Schmidt always wanted to be a better person. His growth is tied to the jar. One of his earliest deposits comes when he tells Cece, “Girl, Imma marry you.” It’s a stupid thing to say to his new roommate’s friend, but as New Girl progresses, it becomes a line of continuity between who Schmidt was and who he wants to be.

By New Girl’s end, Schmidt is happily married and is devoted to his daughter. Items that were once crucial to his identity, such as work, become secondary to his family. He prioritizes a romantic Valentine’s Day with Cece over pleasing his overbearing boss. Vitally, Schmidt learns how to deal with his insecurities. In the past, his weight was a punchline. New Girl, unlike Friends, doesn’t invite its audience to laugh at a character who used to be fat. Instead, New Girl subverts this trope to show how Schmidt’s past treatment causes him to behave inappropriately, without excusing it. This approach to a toxic character is one of New Girl’s biggest accomplishments and something to which modern sitcoms need to pay attention. At the end of his character arc, Schmidt might still be a little too into conditioner (and Nick), but he has learned how to treat other people, and himself, with respect.