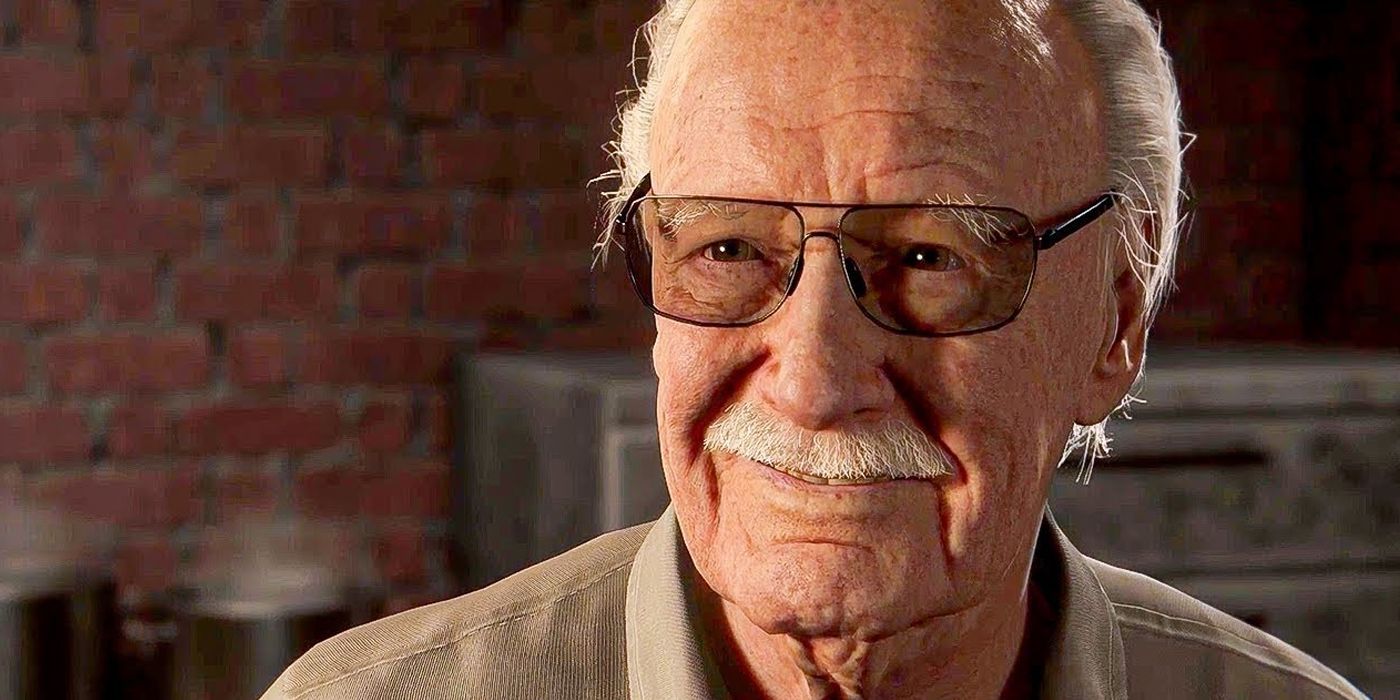

Stan Lee spent decades at the forefront of the comic book industry, and is rightfully revered as one of it’s primary architects. In addition to a prolific comic creator, who introduced the world to most of Marvel’s first wave of iconic superheroes, Lee was also a passionate defender of the medium, refusing to allow anyone to devalue comics in order to privilege other, more prestigious forms of art.

The Comics Journal #42, from October 1978, featured a detailed transcription of Stan Lee’s panel from the Fine Arts Festival at James Madison University in March of that year. The highlight of the wide-ranging conversation was Lee’s vehement defense of comics as an art form, and his dismissal of the idea that comics should, or even can, be considered deferential to more “serious” artistic forms.

Deconstructing the very notion of separating what “is” and “isn’t” art, Lee noted, “I’ve been arguing that subject, or discussing it, all my life,” before launching into an elegant confirmation that comics are, definitively, art.

Stan Lee Wouldn’t Believe How 2023 Rewrote the Cosmic Hierarchy of Marvel’s Gods

2023 saw the most concentrated effort to expand Marvel’s cosmos in the company’s history, an expansion of lore that would make Stan Lee’s head spin.

Stan Lee: “I’d Rather Read A Good Comic Than Listen To A Bad Opera”

“I do feel that comic books are art,” Stan Lee told the crowd James Madison University’s Fine Arts Festival in early 1978. “Just as plays are art, and movies, and television, and sculpture and ballet and dancing are art.” He further noted that any creative endeavor qualified, to him, as art. Instead, the question became a matter of quality, rather than status. He compared comic books to opera, stating that while “comics presently do not enjoy the prestige of opera,” that does not mean all opera is inherently more valuable than all comic books.

As Lee explained to the audience:

I think there can be good comics, there can be good opera, there can be bad comics and there can be bad opera. I’d rather read a good comic than listen to a bad opera. I’d rather listen to, or see, a bad opera than read a bad comic. I think that quality is the big determination for any form of the media.

Understandably, he’s somewhat biased in favor of his medium – but this bias cuts both ways. “I’d rather listen to a bad opera than read a bad comic,” the writer goes out of his way to clarify as he makes his point, indicating the high standards he has for his own art form. Even as he’s defending comics as a legitimate art form, he does admit to considering there to be some form of artistic hierarchy. Good comics may outrank bad opera, but even bad opera is preferable to a bad comic.

Lee’s appearance at the JMU Fine Arts Festival was moderated by a panel, which included Ezra Goldstein, editor of Dramatics, a theater magazine. Goldstein interjected at this point, in response to Lee’s comments:

But in a good opera, for instance, the best operas take us somewhere we can’t go ourselves, and that’s a rather cliché definition for art that you hear sometimes: that it shows us things we wouldn’t see otherwise. I don’t think that definition is applicable to comic books. Would you disagree?

Of course, Stan Lee emphatically disagreed. In a monologue that is still relevant to this same ongoing discussion today, the legendary Marvel creator went on to deliver a substantial explanation as to why he did not agree, while also unpacking Goldstein’s own inherent bias against the comic book medium.

“I Don’t Know How Many People Would Have Ever Seen Asgard Unless They Read Thor”

Stan Lee listed several examples of ways his comic book work fit Ezra Goldstein’s definition of art, for the purposes of their conversation, which Goldstein himself admitted was “somewhat cliché.” In addition to taking readers to the realm of Asgard, he gave readers the opportunity to witness “a guy shoot spider webs,” and all manner of things they might never have conceived of, had he not done it for them. “I think it depends on what the beholder looks for in the product,” he reasoned, venturing to say that:

I’m sure that there are plenty of people who read The Hulk who get nothing out of it, and there may not be that much in it. But there are many other people who read the Hulk who feel they have enjoyed a rare emotional experience.

Here, Lee transitioned into a discussion of “high” and “low” art.

Invoking popular crime novelist Mickey Spillane, and Valley of the Dolls author Jacqueline Susann, Stan Lee noted that this was becoming “a discussion of pop culture vs. ‘culture,’ with quotes around it.” He explained that his lifetime involvement in the art world had led him to know as many “fine artists” as he did commercial artists, noting that he had, “in many ways, more respect for the commercial artist than for the fine artist, because commercial art is a discipline.”

“You not only have to please yourself, but you have to please other people,” Lee said of commercial artists. “[You have to please] a client, you have to please the public.” As an artist, this was always Stan Lee’s first and foremost goal: to please the public. In all his work, he consistently sought to justify his audience’s investment of their time, attention, and money in his art, by giving them something more valuable than, at least, a bad opera. By giving them a good comic.

“I’d Like To Think Someday They Could Read One Of My Stories And Get Something Out Of It.”

The difference between a fine artist and a commercial artist might be intent, Lee explained, but this also changes how the artist approaches their work, and how it is received.

When you’re a fine artist, you do your thing; and if your thing consists of getting a monkey to dip its paws, or claws, or feet, or whatever they call them, in paint, and spatter it on canvas, and then if People magazine wants to give you a write-up, and if people want to buy the paintings, and call it art, nobody can criticize it.

Lee then turned his argument back to the novel, this time bringing some of literature’s greatest heavyweights into the conversation to enforce his point. “Shakespeare was not a fine writer,” the comic book master reminded the audience at the Fine Arts Festival. “Shakespeare was a commercial writer. Charles Dickens was a commercial writer; he was the Mickey Spillane of his day.“

The writer further emphasized: “I don’t think we can really predict what will last, and what’s good at the moment.” Instead, he suggested, the current era’s “low” or “throwaway” art could, in fact, be the enduring works studied by future generations. “We might very well be studying the art of John Buscema some day in the future,” referencing the contemporary comic book artist, “and talking about it the way we talk about Michelangelo.” In this way, Stan Lee made it undeniably clear that dismissal of the comic book medium is a shortsighted view of art.

“I’d like to think that someday they could read one of my stories and get something out of it,” Lee added. Of course, from the generations of talent he has influenced, to books like Stan Lee: How to Write Comics, to his perennial Marvel movie cameos up to his death, American culture has gotten more out of Stan Lee than he could have possibly imagined when his career started in the late 1930s, or even when he gave this speech at the 1978 James Madison University Fine Arts Festival.