For multiple reasons, the origins of the Elder Scrolls franchise are unusual. When the developers at Bethesda Softworks started work on The Elders Scrolls: Arena, the first entry in the popular video game series, they had no idea what “The Elder Scrolls” actually were. It just sounded cool: Elder Scrolls, an ancient source of knowledge that was probably both powerful and dangerous.

As the Elder Scrolls grew into a veritable franchise and game writers starting fleshing out the history and lore of their world of Tamriel, the titular Elder Scrolls grew defined. They were fissures in time that let their readers see the past, present, and future. To read an Elder Scroll without training would drive one mad; to read an Elder Scroll with training would slowly strike you blind. That’s just one piece of the Elder Scrolls world’s weird, sometimes deranged lore, setting details that defy the tropes and conventions of the classic Western Fantasy genre.

The weirdness started, arguably with the ending of The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall, in which several factions tried to seize control of the Numidium, a giant God-Robot forged from brass and magic. Different player choices led to different endings, which presented the game writers with a dilemma: which ending would be the canon ending for future Elder Scrolls titles? The solution they devised was a mysterious event called “The Warp in the West”, in which the Numidium’s activation broke reality, creating a paradox in which all the potential endings for Daggerfall happened at the same time.

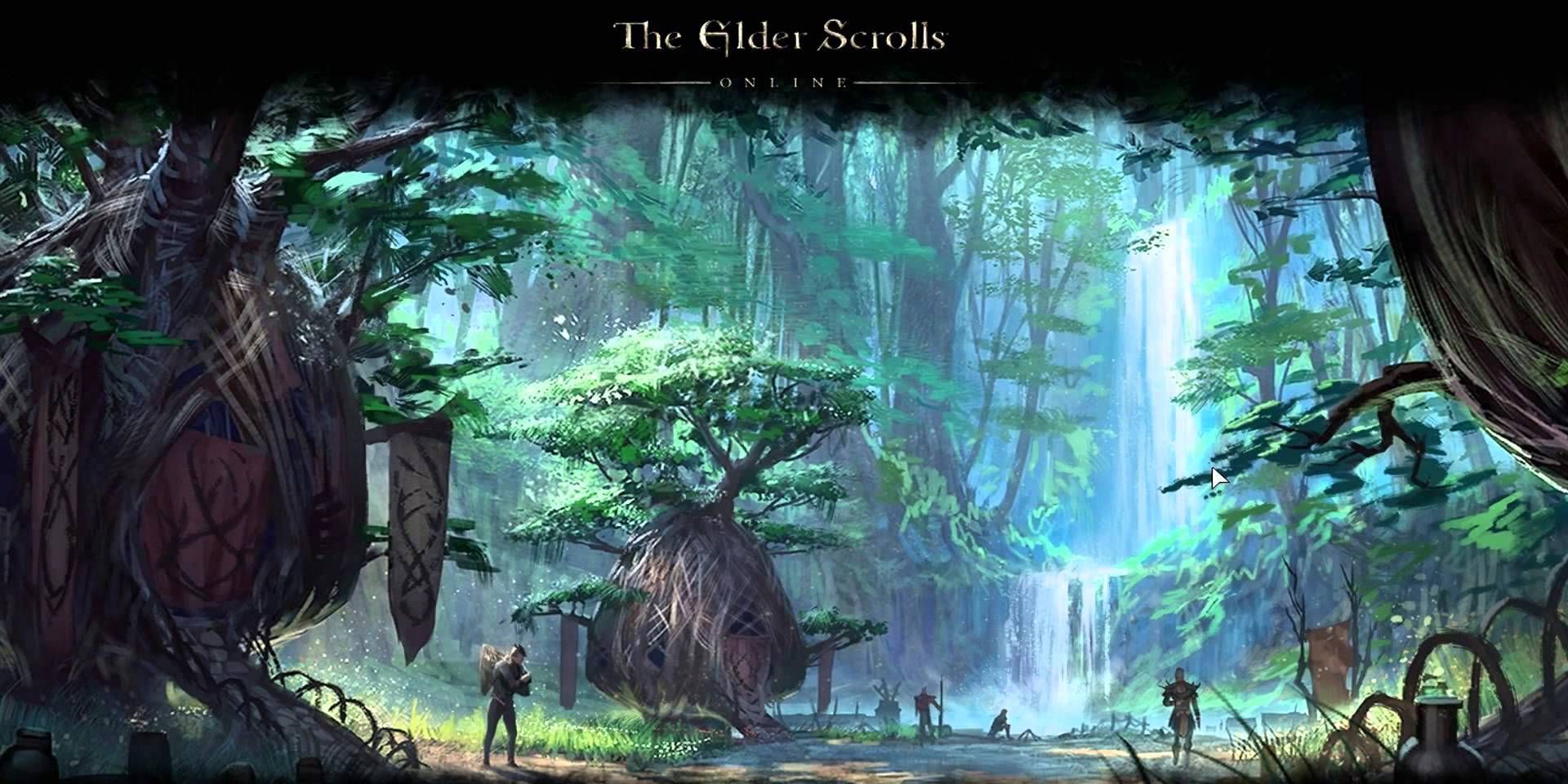

Silt Striders, Mushroom Towers, and Mad Gods

The weirdness of Elder Scrolls lore came out in full with the 2002 release of the Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, a cult classic revered by Elder Scrolls fans to this day for its beautifully alien landscape and musings on the nature of religion and godhood. Writers like Michael Kirkbride introduced characters and myths to the Elder Scrolls franchise that arouse fierce debate among fans to this day. His ideas seeded the lore with the machine-filled ruins of the Dwarves, a high-tech, coldly logical race that deleted themselves from reality in a science experiment gone wrong, the Dark Elves, who live in mushroom houses and ride giant insects, and their rulers, a Tribunal of mortals-turned-Gods who froze a falling asteroid in the air with their power, then made it a prison for Morrowind’s political dissidents.

Dragons, Swordsingers, and Walking Trees

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion and the Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim cleave closer to the Western Fantasy mold than Morrowind, but still contain strong elements of weird fantasy for players willing to read in-game books and uncover secrets. The fascist Thalmor Elves, the secondary antagonists of Skyrim, plot to destroy the material world by killing Talos, the God of humans. The Wood Elves of Valenwood make their homes in giant walking trees and practice a religion mandating an all-meat diet and ritual cannibalism of their enemies. The Dragons of Skyrim, according to Michael Kirkbride on Tumblr, were originally conceived as “biological idea-eating time machines“, while the Redguard culture of Hammerfall is famed for their legendary Swordsingers, blade-masters whose keen “Spirit-Swords” can split the atom and kill the laws of nature.

The strange lore of the Elder Scrolls series offers exciting narrative possibilities for The Elder Scrolls 6, still in early development. Some think this sequel will take place in Hammerfall or another Redguard-centric land, picturing a fantasy game inspired by African myth and culture, with the mastery of enlightened sword techniques a key Elder Scrolls VI gameplay mechanic. Others hope to learn more about the Thalmor and their plan to dissolve reality. Whatever form the story of The Elder Scrolls 6 takes, it will undoubtedly draw from the rich world established by its prequels, a living dream both real and unreal.