Warning: Spoilers for Beau Is Afraid aheadBeau Is Afraid is a tough film to get a handle on, especially on first watch. It’s not only that the story has left people puzzled (though it certainly has), but that the way it makes you feel can vary wildly, even within a single scene. Ari Aster’s first two features, Hereditary and Midsommar, established him as one of today’s foremost purveyors of cinematic dread. This latest project is no less ‘dreadful’ – some scenes, when taken alone, would feel right at home in a horror movie. But Beau Is Afraid also parodies the preoccupations of his previous work, leaving us with something that is undoubtedly a comedy, but doesn’t always feel like one.

For me, my initial viewing experience was akin to emotional whiplash. I left the theater lacking the vocabulary to describe even what kind of movie this was, let alone explain Beau Is Afraid‘s ending, and anytime I would try eventually devolved into an awkward recounting of the movie’s premise. But the way the film turns Beau’s nightmares into punchlines while still putting the audience in a position to empathize with his terror at experiencing them left me captivated nonetheless, and eager to pin down just what, exactly, I had watched.

A Beginner’s Guide To Understanding Beau Is Afraid

Aster has referred to Beau Is Afraid as first and foremost a picaresque, but I believe it’s best understood as a ‘cosmic comedy’ – a comedic reworking of cosmic horror. The subgenre most closely associated with H.P. Lovecraft shares a great deal with this movie. Its characters typically encounter something they were never meant to see, something ancient and terrible and fundamentally beyond their understanding. A peek behind the curtain, however brief, reveals humanity as so insignificant in the grand scheme of things that the looker’s mind is left irrevocably shattered. Cosmic horror fiction is characterized by a feeling of dread at living in a world indifferent to us at best, actively malevolent at worst.

These stories rely on the imagination in a way that makes them challenging to film, but Aster’s movie succeeds for the exact reason many straight adaptations fail: visualizing unknowable, mind-breaking truths tends to make them a lot less frightening. Beau Is Afraid is cosmic horror reflected in a funhouse mirror. Instead of de-centering the human race to bone-chilling effect, this universe revolves entirely around one specific man, and the narrative essentially documents his discovering that very fact. Looking more closely at how this film handles its cosmic comedy makes its tone much easier to grasp, and once you understand how this movie strives to make you feel, the way it all fits together starts to make sense.

The Cosmic Comedy Of Beau Is Afraid, Explained

What would it be like if a look under the hood of the universe revealed it to be arranged around one neurotic, middle-aged man’s fraught relationship with his mother? Terrifying for that man, certainly – but one man’s terror is a viewing audience’s schadenfreude. Beau Is Afraid straddles these two emotional impulses by having us experience both. The conventions of cosmic horror at play, as well as certain aesthetic choices that bake them into the film’s form, create a great deal of fear in Beau, and our closeness to his perspective allows us at times to feel it with him. But the ways in which these conventions are played with creates just enough distance to find the humor in how perfectly this world was tailored to make Beau as miserable as possible.

Cosmic Horror Played Straight: Beau Skips To The End

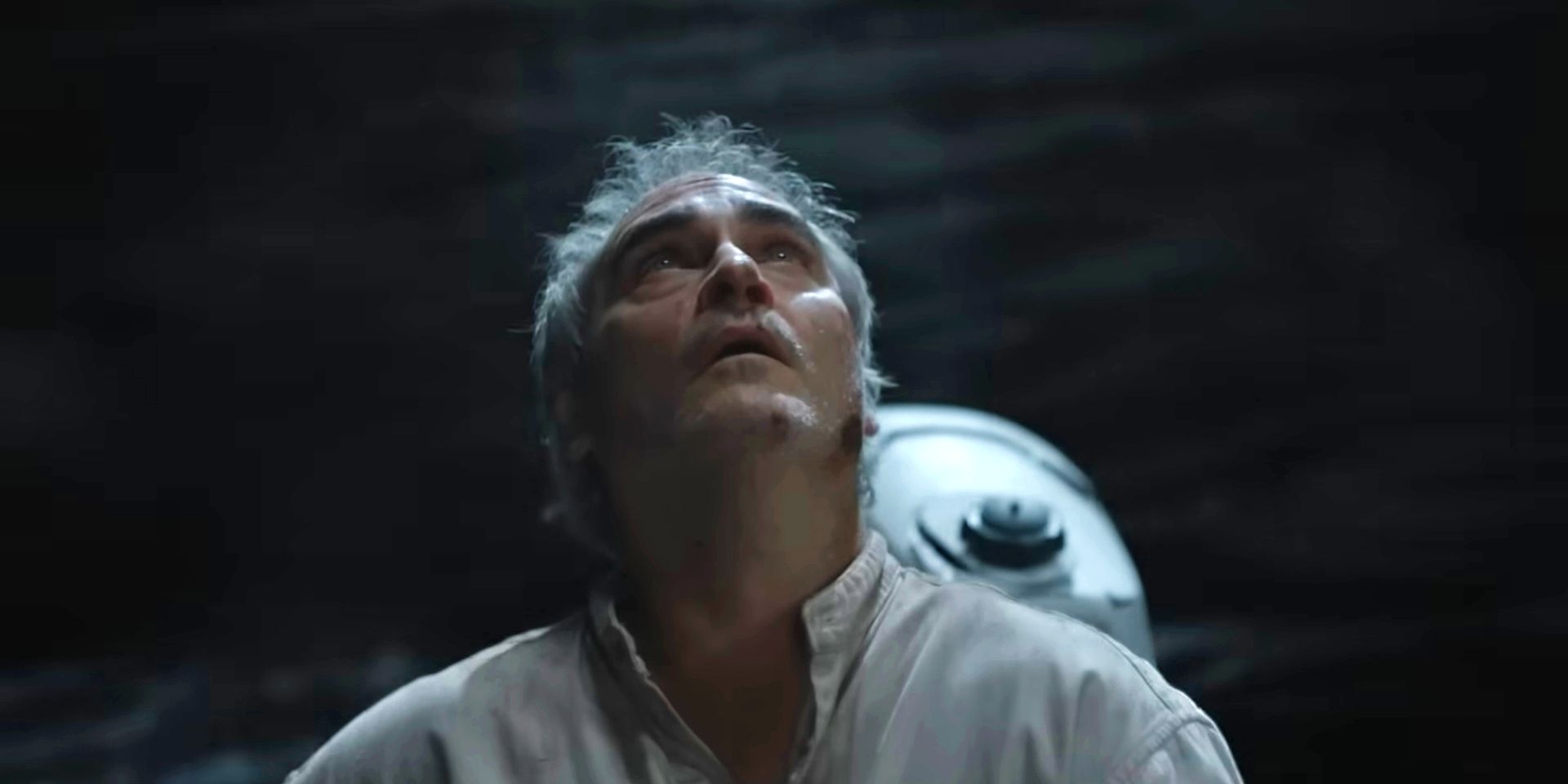

Predestination is often a feature of cosmic horror fiction and, indeed, of Aster’s work. From the opening scene of Beau Is Afraid, which shows his birth from his perspective as his mother’s nervous voice echoes around him, Beau’s life is tinged with a sense of doom. This then manifests in ways both big and small. His first phone call with his mother, to inform her he won’t be able to make his flight, is filmed with a slow, controlled zoom into a closeup on Joaquin Phoenix’s face. A common trait of an Aster camera, it not only reinforces Beau as the film’s axis, but makes the scene feel as if it’s building to an inevitable endpoint. Beau’s dread at making this call drives the viewer’s experience of it as well.

Of course, while choices like this make Beau feel doomed, his fate actually is sealed from the beginning – his therapist writing “guilty” on a notepad presages the verdict of his last-act trial, Beau Is Afraid‘s premise wrapped neatly into a single pun. This final sequence is foreshadowed in moments as diverse as a boy’s toy boat capsizing and a glimpse of sparkling wake tacked onto Beau’s recurring dream, but one scene in the film’s suburban detour takes things a significant step further. Having been warned by Grace to stop incriminating himself, to his and our bewilderment, she directs him to turn the TV to a specific channel. There, he discovers he’s being recorded from a camera hidden somewhere in his host family’s living room.

Beau rolls the tape back, just to confirm what he’s seeing, and re-watches the scene we just saw play out. Then he hits fast-forward. In a moment of true cosmic horror, he glimpses Beau Is Afraid‘s ending; forbidden knowledge neither he nor a first-time viewer have the tools to understand. The film pulls away before either can gain clarity, but the implication that this nightmarish odyssey is barreling toward a pre-set outcome has left its mark. Moments like these are wrapped up in Beau’s emotional journey, and make up the more serious strain of the film’s affective impact. This is in part because, like traditional cosmic horror fiction, they involve an encounter with some outside force exhibiting frightening powers of control.

Cosmic Horror Played For Laughs: Beau’s ‘Condition’

To turn that dynamic on its head, Beau Is Afraid often redirects its gaze inward, making things as specific to Beau as possible. The early section of his life in the city sets this up well, using another of Aster’s visual trademarks: a dense mise-en-scène. This cityscape is hellish, but in an exaggerated way that encourages us to look at it as more than literal; the level of detail built into the frame calls attention to how carefully this world has been constructed, not just by Aster, but by Mona. Everything scary about Beau’s street, from knife-wielding homeless people to trigger-happy cops to a man covered head-to-toe in tattoos, are things a stereotypically overprotective mother could invent as dangers of urban living. His travails in this first section get progressively funnier as each new layer of unpleasantness is peeled back to reveal another.

Predestination, too, is shifted internal and wielded for laughs, by invoking genetics – namely, the story young Beau is told about his father dying of a heart defect the instant he was conceived, leaving him with the life-defining fear that having an orgasm would kill him. It’s darkly hilarious, the sexual hangup to end all sexual hangups, but it’s also Beau’s first time grappling with his own predetermined end. It fuels many of the movie’s punchlines, none more cosmically comic than after he finally sleeps with his childhood crush, Elaine. He survives, to his genuine relief and elation, only to be thrown back into horror by discovering she has died on top of him. His first sexual experience, in an absurdly poetic twist of the knife, echoes his mother’s role in the story instead of his father’s.

When It All Comes Together: Beau’s Dream & Mona’s Attic

The cosmic horror inversion most prominent in Beau Is Afraid, and most central to understanding its aims, is of the all-important convention of forbidden knowledge. Alongside Mona constructing Beau’s life as a test of filial piety, there is forbidden knowledge locked inside Beau’s mind, represented by a recurring dream. It is teased to the viewer in flashes, starting from the opening therapy session, and requires exploring some of his personal history to understand. In it, there are two Beaus; one, the dreamer, is represented by the camera. The other is a young boy brave enough to confront his mother and demand to see his father, after which Mona leads him into the attic, a place Beau was told never to go. Brave Beau is shut inside, while dreamer Beau remains downstairs, ignorant of what lies within.

This dream, and in turn the truth about Beau’s father, is treated as seriously as the prophetic security footage – meaning it’s eventually revealed as one big joke at Beau’s expense. As the outward strand builds to a trial of mythic proportions, the inward one reaches its climax when Beau finally confronts Mona about his father, and learns the attic is real. She closes him in, telling him that his recurring dream was actually a memory. Terrified, he turns on a flashlight and first notices an unkempt, malnourished version of himself (or, if you’re so inclined, a long-lost twin brother) chained to the floor. Then Beau sees his ‘father’: a giant, monstrous penis, who bellows with happiness at their reunion before a violent interruption allows a screaming Beau to escape the attic.

Without the story specifics, Beau goes somewhere forbidden, sees a horrifying creature beyond his understanding, and (temporarily at least) loses his mind. Cosmic horror par excellence. But in context, this scene takes something that shaped Beau’s life and distills it down to a penis joke. Try to interpret it, and you’ll find many possible ways to understand it, both literal and metaphoric. But a cosmic comedy doesn’t always value understanding. What seems more important to Beau Is Afraid is staging an encounter with the unknowable, turning it into something we both recoil from and laugh at, and leaving us to sort through the emotional aftermath.

What Beau Is Afraid Actually Means

If the lens of cosmic comedy helps to make sense of Beau Is Afraid as an emotional journey, can it also help find meaning in its content? To an extent – as the attic scene illustrates, its constituent parts are not meant to be ‘solvable’ in the way of a puzzle film. Neither is it the kind of movie that finds meaning entirely in how it makes someone feel, when trying too hard to understand its story risks missing the point. Aster’s created something in-between, and its grand design is most visible in the odyssey as a whole, particularly the way it foregrounds Beau’s psyche.

From the jump, Beau Is Afraid raises doubts about this world’s true nature: Is all this ‘real’ within the construct of the film, or are we in some way inside the protagonist’s head? A be-all-end-all question for some films, but not one this movie cares to answer, besides saying yes to both. The narrative can be approached literally and as a reflection of Beau. Many have highlighted how well the first act recreates what it feels like to live with anxiety through surreal means, and every section of the film could probably be interpreted this way, each shedding light on a different part of Beau’s experience. (That animated sequence? I read it as either the folly of living vicariously through art, or through self-help tapes and guided meditations.)

When taken together, however, it starts to look like Aster’s movie is analogous to how undergoing therapy can feel. Aside from literally introducing adult Beau in a therapy session, the movie is filled to the brim with areas of psychoanalytic interest, from dreams and memories to familial toxicity and sexual dysfunction. His journey takes him through different versions of family: WASP-y suburbanites with a son-shaped hole to fill; a found-family traveling theater troupe made up exclusively of orphans; a potential romantic partner. These encounters prompt him to examine what it is he wants and why he doesn’t have it, and in response, he revisits formative memories and tries to break behavioral patterns. As Beau moves through the world, he also confronts and tries to process his trauma.

Therapy (& Therapeutic Art) as Cosmic Comedy: Beau’s Trial

In this light, Beau Is Afraid‘s cosmic comedy takes on new meaning as an approximation of this experience. Beau goes through all this turmoil to excavate the repressed corners of his mind, and each time he unearths a Freudian cliché. His problems, which feel so deeply personal, are just (admittedly heightened) variations of the same mommy and daddy issues that have plagued humankind since Oedipus. He bares his soul only to end up looking ridiculous.

But most people can take comfort in only looking ridiculous to their therapist – Beau’s mind, thanks to a worst-case-scenario desecration of doctor-patient confidentiality, is exposed to everyone. And upon seeing what he tries to hide from the world, we gasp, or chuckle, or shift uncomfortably in our seats. We are as complicit in judging Beau as everyone he encounters, because how could you not judge a man for having a kaiju phallus for a father?

Perhaps the goal of Beau Is Afraid is more accurately to share what it can feel like to make therapeutic art. After all, Beau’s last moments are spent in view of the masses as they literally determine whether he will sink or swim; when it’s all over, the film tellingly holds on the crowd filing out of the stadium as the credits roll, just when the real-world audience in a movie theater would be doing the same. Maybe, after living through all Beau’s trials with him, we’re supposed to leave with a little more empathy for people who experience the world the way he does, or for those who choose to mine their lives for our entertainment.

If that sounds to you like too (self-)serious a reading for a film this openly self-depracating, it does to me, too. So, keep in mind that cosmic comedy treats profundity as the set-up for a joke – and before we the audience even had the chance to pass judgment on Beau Is Afraid, Aster just went ahead and sunk Beau for us.