Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton focuses on the life of founding father Alexander Hamilton and the birth of the United States, but it glosses over some important details. Of course, given time constraints and poetic license needed for the music, the play was never going to hit every note from the history books, but a few of the movie’s major plot threads were still incomplete compared to actual events.

Hamilton follows Hamilton’s life from birth until death, but the story does not truly set in motion until the beginnings of the American Revolution. From there, audiences watch Hamilton’s participation in the Revolutionary War, rise to Treasury Secretary, family drama, and his eventual murder at the hands of former Vice President Aaron Burr. Hamilton makes history entertaining and lively—but it occasionally does so at the expense of accuracy.

Like many biopics, Hamilton takes some creative liberties to make the story smoother and more thematically coherent. But after all the singing, dancing, and murder is said and done, many viewers want to know why Hamilton left out or altered certain parts of American history. Let’s break down the three most substantial inaccuracies in Hamilton and how they changed the play.

Hamilton’s love triangle with Eliza and Angelica

Hamilton dedicates two songs to the love triangle between the two Schuyler sisters. In Helpless, Angelica introduces Eliza to Hamilton, and by the end of the song, they’re married. In the following song, Satisfied, Angelica reveals that she loves Hamilton, but she would rather let Eliza be happy. She states her reasoning: “I’m a girl in a world in which my only job is to marry rich. My father has no sons, so I’m the one who has to social climb for one.” She also worries that Hamilton is only interested in her for her status and that she wants Eliza to get the man that she loves.

In real life, Angelica was already married when she met Hamilton, so he was never an option for her. Additionally, her father had two sons. In an interview with Genius, Miranda says that he forgot about Angelica’s brothers: “I think my brain wanted to forget because it’s stronger dramatically if societally she can’t marry him.” He goes onto say that the two songs are a microcosm of one of Hamilton’s major themes: that our accounts of history depend on who tells the story. Miranda’s statement that this version of events strengthens the story’s drama is correct. Because of the love that hangs just out of reach, Hamilton and Angelica’s letters feel more meaningful, her anger towards him in The Reynolds Pamphlet feels more palpable, and her presence at his death-bed is more logical.

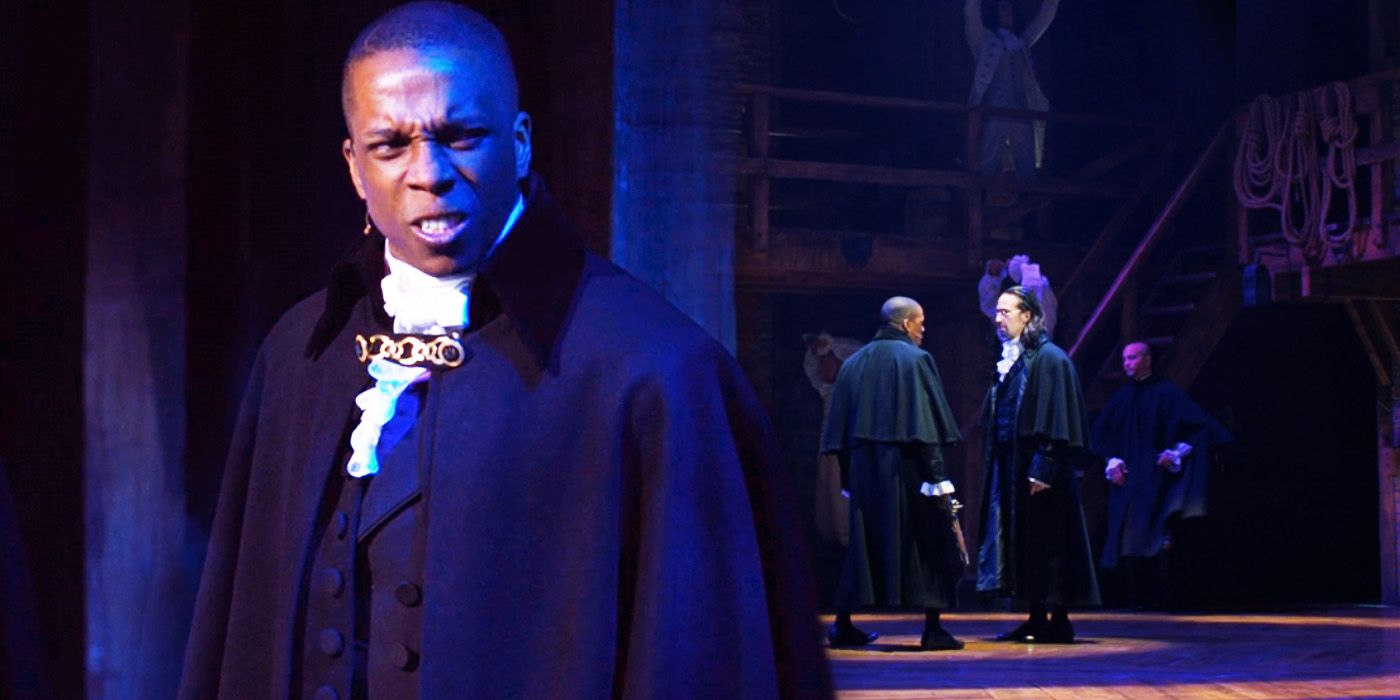

Aaron Burr’s feelings about Hamilton’s death

After Burr kills Hamilton in a duel, the play portrays him as regretful. After he shoots, he sees Hamilton pointing his gun towards the sky, and cries, “Wait!” For the remainder of “The World Was Wide Enough,” he is visibly devastated and refers to Hamilton’s murder as a mistake. He sings, “I should have known the world was wide enough for both Hamilton and me.” In real life, however, Burr was not this remorseful. According to Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton, the book Hamilton is based on, Burr often laughed about Hamilton’s death and referred to him as “my friend Hamilton—who I shot.”

Portraying Burr with no remorse would have overly simplified his characterization in Hamilton. Burr is one of the musical’s most intriguing characters, primarily because he is too complex to be categorized as either a hero or a villain. His character is marked by contradictions: he gives Hamilton genuine political advice but also undermines him when necessary. He sings tenderly alongside Hamilton about becoming a father, but he ultimately kills him. Showcasing Burr’s true attitude towards Hamilton’s death would have completely undermined his complexity and left little room for character development. By showing remorse towards Hamilton’s death, Burr shows his humanity—he is more than just a simple villain.

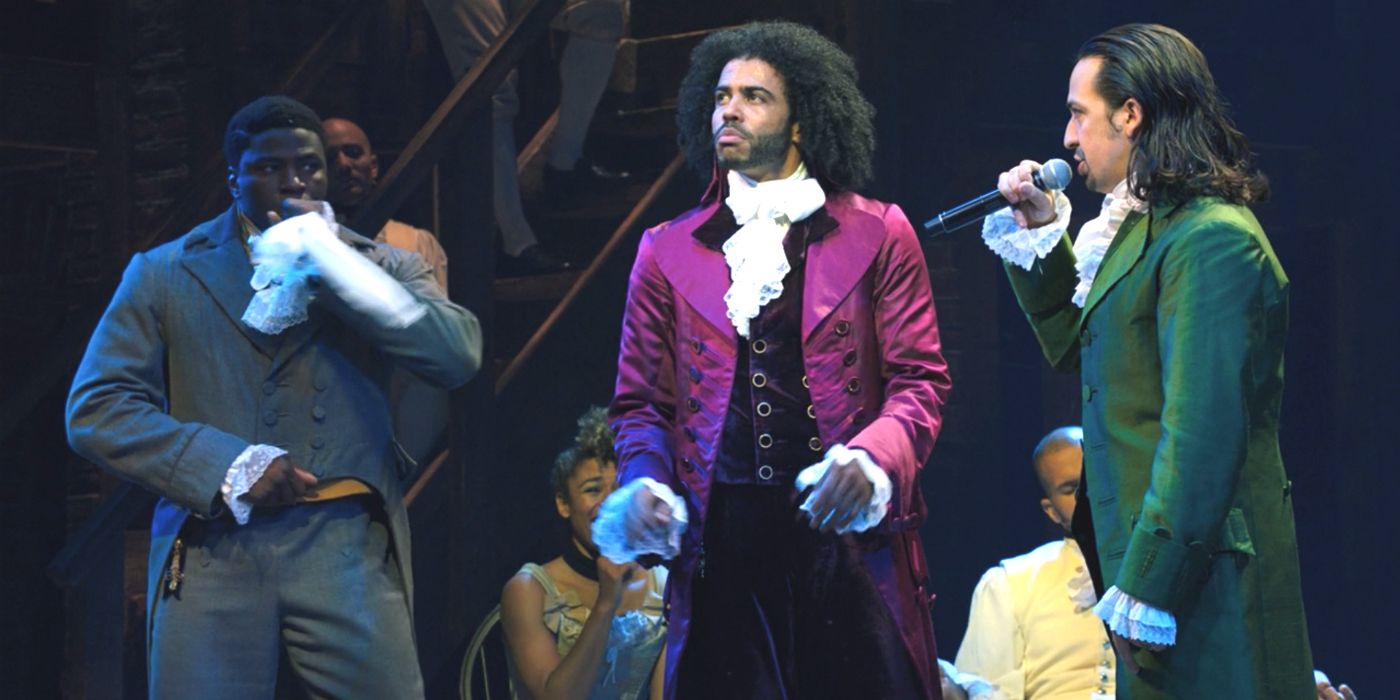

The Founding Fathers and Slavery

Hamilton certainly does not ignore slavery, but it does portray the founding fathers’ participation in it inaccurately. In Act 2, Thomas Jefferson makes an entry as one of the musical’s antagonists—and Hamilton showcases his use of slavery to confirm his position as a villain. In “Cabinet Battle #1,” Hamilton calls Jefferson out on his use of slaves: “A civics lesson from a slaver. Hey neighbor, your debts are paid because you don’t pay for labor.” This line—along with Hamilton singing along with Laurens in “The Battle of Yorktown,” “we’ll never be free until we end slavery,”—gives audiences the perception that Hamilton was an abolitionist. What Hamilton fails to mention is that Hamilton, Washington, and the Schuyler sisters, some of the play’s heroes, all perpetuated slavery.

Hamilton’s relationship with slavery is far more complicated than its portrayal in the musical. Hamilton was opposed to slavery ideologically, but every time that belief conflicted with his ambition, he chose his ambition. He married into a wealthy, slave-owning family and helped his sister-in-law acquire a slave. Additionally, Hamilton’s grandson claimed that Hamilton himself owned slaves. If the musical included the reality of Hamilton’s history with slavery, it might have undermined the audience’s view of him as a hero.

Hamilton employs a similar tactic with its portrayal of Washington. Washington’s history of slavery is too well-known for Miranda to present him as an abolitionist—instead, he opts to ignore it. It is clear what Miranda accomplishes with the discrepancy between Jefferson and other slave-owning founding fathers. Hamilton names and shames Hamilton’s enemies as slaveowners, but either ignores or misrepresents Hamilton and his friends’ relationship to slavery. With this methodology, Miranda uses slavery as a tool to differentiate between the musical’s heroes and villains. Our protagonist becomes more comfortable to root for, and our antagonist becomes easier to hate.

Hamilton is a musical, not a documentary. However, that does not stop the play from having a significant impact on viewers’ perceptions of American history. Miranda took creative license to make the musical smoother and more entertaining, capturing the essence of each character rather than the details. Still, it is crucial to be aware of the play’s historical inaccuracies—especially when discussing something as historically significant as slavery.

The changes that Miranda made to history improve the musical as a piece of art and entertainment. The inaccuracies regarding Angelica’s marriage tell the story more efficiently and meaningfully, and the portrayal of Burr’s regret helps to humanize him. Hamilton’s description of slave-owning founding fathers helps the audience know who to root for but is still understandably controversial. While Hamilton’s inaccuracies certainly improve the play, many disagree on the impact that the play has had on mass understanding of history.