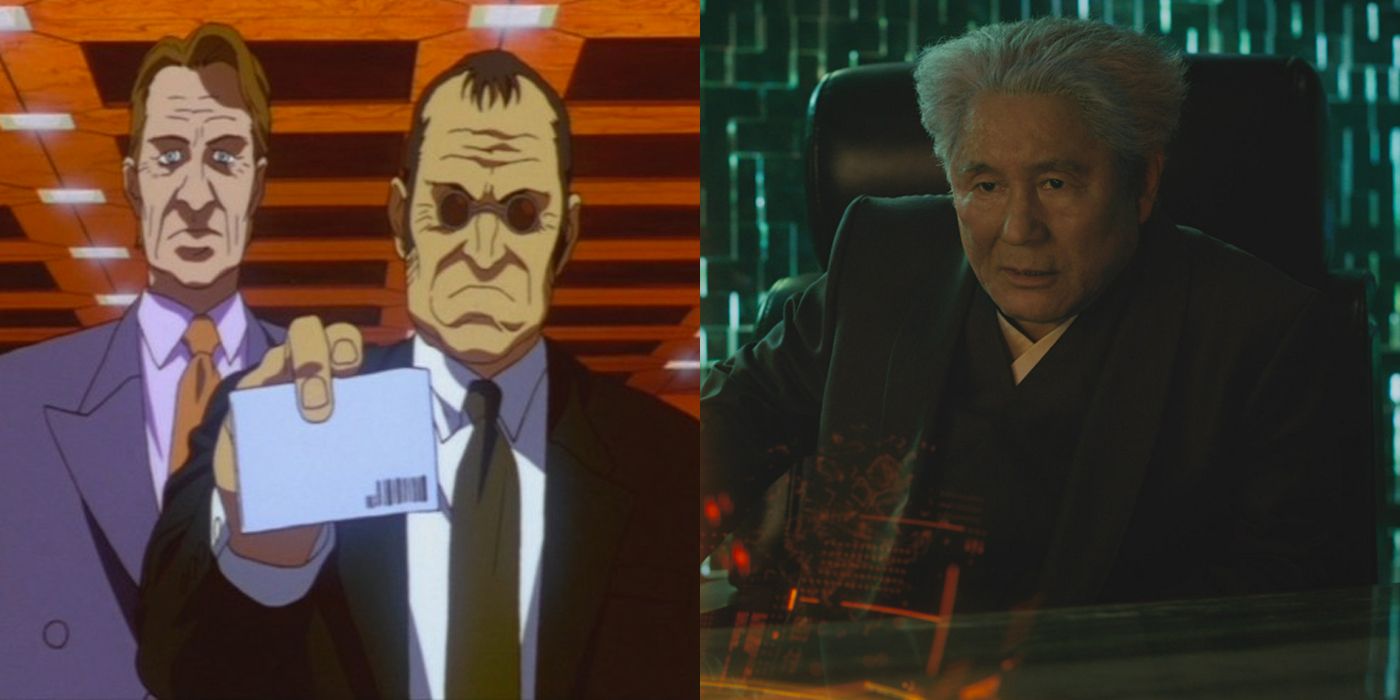

Through its long development the live-action Ghost in the Shell has been known as a remake, although that’s not quite accurate. The 1995 anime is far-and-away the most well-known product with the Ghost in the Shell name, but it’s just the tip of the massive Japanese franchise; Mamoru Oshii’s animation was an adaptation of the original manga, which has been further mined not only for sequels, but also TV shows and video games. That’s decades of material there to be mined.

So while Rupert Sanders’ film, which stars Scarlett Johansson in the lead role, definitely has elements most prominently taken from the famed movie, it’s more than just a one-to-one retelling of the story. It lifts from the original source, TV shows, and throws in quite a lot of new ideas as well.

In a macro sense, the film is made with a very clear vision in regard to how it handles its main character and most of the changes and various inspirations come from that decision. To highlight Sanders’ various influences, here’s a breakdown of all the major differences and deviations made by the live-action version, compared to predominantly that original film but also the wider franchise.

Major’s Past Vs. Major’s Future

The core distinction between Ghost in the Shells 1995 and 2017 is in their main character and the focus of her arc. The Major (Motoko Kusanagi in the original, Mira Killian in the live-action movie) is a highly advanced cybernetic individual, with her human brain placed in a wholly robotic body. The difference comes in focus: The anime is very much about her future – across the events of the movie, she has her mind melded with a rogue program and is ascended to a higher state of being – while the remake is intensely concerned with her past; Major’s pre-cybernetic history was always vague in the previous franchise (bar a few key elements we’ll get into later), but here it’s the plot’s driving force.

Throughout the story, Major is suffering from glitches of her pre-cyborg life, which leads to her doubt about whether she’s truly real (in the original that question is posed organically). It’s eventually revealed in the third act that Mira is actually the brain of a Japanese runaway called Motoko Kusanagi with her memories wiped and used by the insidious Hanka Robotics as part of their ongoing tech exploration. This is obviously an attempt to address the whitewashing concerns, but it also alters the wider scope of the character; whereas it wasn’t until the end when Major ascended, in the new movie it’s cited multiple times that she is already “the first of her kind,” meaning that the tech breakthrough we’re meant to be in awe of here isn’t an organic mind going digital, but the basic creation.

Beyond the origins and exploration, though, Major’s temperament isn’t all that different. Johansson plays Killian/Kusanagi as a calm, adept fighter and lets most of the weighty personality come from her subtle eye movement. Many of the other changes are cosmetic. Her robot body is made up of artificial skin plates, but it’s altogether smoother – there’s no faux-nudity, presumably to lock the film’s PG-13 rating – and her creation sequence that opens the film is more elaborate and ethereal, making it a greater visual spectacle (and highlighting how new age it is even in this sci-fi world).

How Batou Got His Eyes

Batou, Major’s partner at Section 9, is here played by Game of Thrones’ Pilou Asbæk. The character in the animated version is rather serious and job-focused, but in Sanders’ movie the edges feel a little less extreme; he’s obviously not as cartoonishly large and because of that (and Asbæk’s affable performance) Batou doesn’t come across as intimidating, making him more all round wholesome. He’s able to hold himself in a fight and comes across as a loner, yet is ultimately a kind, relatable person. This is actually a little closer to the original manga, where he was an overall lighter presence. There are also elements from the sequel, Innocence, brought over, specifically his close relationship with a pack of stray dogs.

The big alteration worth commenting on is augmentation. Batou is best recognized by his prosthetic eyes – two small, grey implants. The live-action film explains the origin of this, and in doing so alters the character’s attitude; here Batou is against upgrading and only does so after he’s injured on the job. It’s used in the film as a way to show the various stances on the rise of technology without having to venture too far from the story, and while it’s a change to his personality, it does somewhat fit.

Kuze Is A Mixture of Two Characters

The villain of Ghost in the Shell is set up as Michael Pitt’s Kuze, a cyber-terrorist with his sights set on taking down Hanka. It’s later revealed, however, that he is one of the 98 previous attempts to create a being like Major who’s trying to highlight their immoral practices. It transpires both he and Kusanagi knew each other before they were experimented on, and once she’s discovered their past, the pair team-up against Hanka CEO Cutter.

This is a mixture of the Puppetmaster from the anime and Kuze from Season 2 of the TV series. The general narrative setup with him a person of interest for Section 9 isn’t dissimilar to how the former is introduced (albeit without political involvement, which we’ll look at in a moment) and the final showdown in a decrepit building against a spider-tank is visually similar. In fact, 2017’s Kuze could be read as something of a companion piece to Puppetmaster; his primary plot necessity is to further along Major’s awakening, albeit in a different manner.

In terms of actual personality, though he is still an approximation of the source Kuze, right down to his intricate link to the Major’s past. The big change – beyond Pitt’s highly robotic performance – is the influence he plays on Mira; the show had a less amnesia-focused plot and thus no secret identity to mine, and their link was a simpler emotional one.

The True Villain Is Corporations (With No International Relations Problems)

On a thematic level (and putting aside Major’s past elements), Ghost in the Shell 2017 is roundabout dealing with similar ideas to the 1995 movie; the ethics of cybernetic enhancement and, as an extension, what it means to be human.

The one thing it sidesteps almost completely is any of the political conflict that dominated the first film. The opening text alone established that for all the tech advancements the world was still dictated by modern issues; “The advance of computerization, however, has not yet wiped out nations and ethnic groups.” This was highlighted by the plot, which had Puppetmaster an American creation and Batou and others in counter-terrorist Section 9 wary of working with other groups, specifically intelligence-based Section 6. Within all this, Megatech, the company originally behind the Major and from where Puppetmaster tries to escape, is pretty much a third party.

The reboot ditches much of this or otherwise relegates it the background; we don’t delve much into the global political situation and the villain is straight-up the CEO of Megatech equivalent Hanka, who is solely responsible for the creation of the new machines. This, of course, neatly allows the film to play internationally without offending any potential markets, but in the context of the franchise suggests that the world Sanders has created is a step forward from what we saw twenty years ago; nations have begun to be “wiped out”. It also allows the film to take a more modern target at conglomerates, in the modern era certainly a more pressing concern.

The World Is More Advanced

Stepping out of political intrigue, Ghost in the Shell 1995 presents a run-down near-future where – as it is in the real world, but which sci-fi often ignores – all modern tech has been built atop the old (a fitting representation of the movie’s cybernetics). The Japanese city the action is set in has been striken by a flood, leading to streets becoming canals and vast waterlogged expanses. It’s implied this is the result of climate change, which plays into the advancement of society now on the brink of change.

The remake is ostensibly the same, but has some fundamental alterations under the surface. The style is altogether more typically futuristic (as opposed to the original’s Blade Runner-inspired tech noir), with giant hologram adverts over the city and the flood less prominent – it only appears to effect certain parts – but where it’s most prominent is again in the idea of nations and ethnic groups. The world is pointedly more multicultural and culturally diverse (bi and trans characters appear with minimal remark. That’s in part due to the film’s westernization, but it provides a strong backdrop for the alteration to Major’s past. As already stated, the Japan-America politics of the original are gone (the villain is a company, not a country) and immigration is a repeated reference, putting is a world one step closer to the one promised in the original. Even more subtle things push us further ahead; instead of the San Miguel product placement, the beers drank in the new film come in slightly streamlined cans.

Beyond story concerns, this is likely also somewhat influenced by the changes that have occurred in the real world in the two decades that necessitate a move forwards. On that note, the one area where the world doesn’t really advance is in its use of standard technology; being rather forward thinking for a pre-online sci-fi, Ghost in the Shell always had a pretty accurate hold on what the internet-enabled world would look like.

Conclusion

If we’re talking direct comparisons to the original movie, the biggest cases are the major set pieces – the opening building jump, the water fight and spider-tank battle – which all have their unique alterations: the leap has the same camo-reveal, but Major is interjecting in a business meeting gone wrong instead of a political rendezvous (the geisha robots are also cribbed from the second movie); the water fight has Major against the mind-hacked truck driver rather than the hacker himself; and the spider-tank has similar action beats (hiding behind columns, the machine grabbing a character by the head, Major ripping it apart and tearing off her own arm) but is overall a leaner scene.

Each of these is rather faithfully recreated, with Sanders taking cinematography cues from the source but twisting them to fit the world; these are essentially moments of recognizable imagery transplanted into the new story rather than direct recreations, which is a pretty apt summary of the whole film. It’s not a remake, it’s a repurposing.

Next: Ghost in the Shell Tries To Own its Whitewashing… And Fails

Key Release Dates

Ghost in the Shell

Release Date:2017-03-31