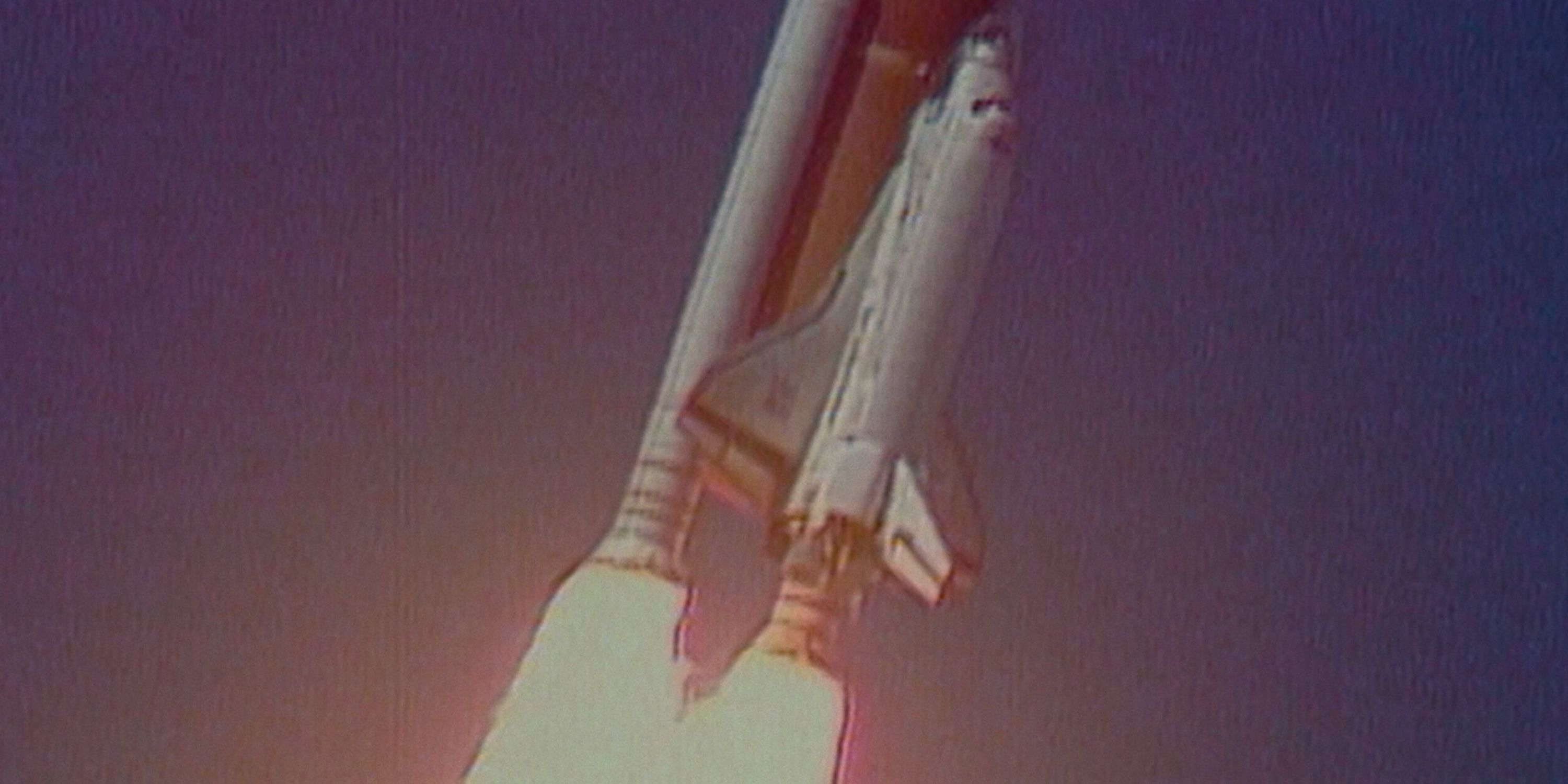

Challenger: The Final Flight clears up misconceptions about what actually caused the 1986 NASA disaster. Decades after the Challenger space shuttle disintegrated on live television, people familiar with the event seem to remember the specifics differently. What’s clear, though, is that a major malfunction led to the deaths of seven U.S. astronauts.

Divided into four parts, Challenger: The Final Flight primarily focuses on the years leading up the the Challenger mission. And within the first 10 minutes of Challenger: The Final Flight, former NASA Resource Analyst Richard Cook recalls watching news coverage about the Challenger disaster and thinking that “a cover-up was in motion.” The docuseries expands on that idea with on-camera commentaries about the Utah-based contractor Morton-Thiokol, which was responsible for manufacturing the Challenger’s boosters. Leslie Serna, a former Morton-Thiokol employee and the daughter of an engineer who worked on the boosters, recalls her father being “visibly distraught” and stating that “the shuttle is going to explode.” Bob Ebeling was right about the Challenger’s booster issues, but his concerns were dismissed by NASA.

Challenger: The Final Flight’s second episode explains why the Challenger disaster happened. Former Morton-Thiokol engineer Brian Russell reveals that the craft’s boosters were recovered after the tragedy, and that his company was able to “evaluate the performance.” Morton-Thiokol discovered that both O-rings (booster sealers) had malfunctioned, which led to the fuel tank blowing up. The Challenger itself didn’t technically “explode” but rather disintegrated from the result of the O-ring malfunction. The crew members’ cabin remained in tact but fell to the Atlantic Ocean at approximately 200 miles per hour.

On October 1, 1985 – about four months before the Challenger launch – Ebeling wrote a memo his Morton-Thiokol boss, Allan J. McDonald, that began with “HELP!” The engineer went on to express his concerns about task force delays and described them as a “red flag.” From there, Morton-Thiokol reached out to NASA about ongoing O-ring problems and scheduling issues. One day before the challenger launched, Morton-Thiokol had a conference call with NASA about the weather conditions, and stated that they couldn’t guarantee that the O-rings would seal the boosters if they were cooler than 54 degrees Fahrenheit.

NASA rejected a delayed launch proposal – which has been attributed in the past to NASA not wanting to impede momentum in the space shuttle program, which was only created a decade before and began launching a few years prior to the Challenger’s mission – and Morton-Thiokol was later found liable for the Challenger disaster. The Final Flight on Netflix includes numerous interviews from people who worked at both companies.