Alfred Hitchcock is known as one of the greatest film directors of all time with a career that began in the silent era and lasted through the horror craze of the 1970s, but there are several unmade Hitchcock films that could have further elevated his mastery. With more than 50 American and British directing credits over a span of five decades, Hitchcock made his mark on not only the thriller, mystery, and horror genres but cinema as a whole. Though his vast filmography has inspired generations of directors, actors, and screenwriters to come, Hitchcock only had a few movies nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, one win, and no Oscars for Best Director. The “master of suspense,” as he is known in the industry, was never properly awarded for his contributions despite the cultural impact he continues to bear today.

Not only did his direction inspire techniques like the dolly zoom, slow staircase ascensions, and high angle shots that modern directors continue to employ, Hitchcock enhanced the careers of some of the greatest actors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Besides his typical “Hitchcock blond” leads like Eva Marie Saint, Grace Kelly, and Janet Leigh, Hitchcock exploited the talents of screen legends James Stewart and Cary Grant as his leading-man muses in the 40s and 50s. Some of his most everlasting films like Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958), and North by Northwest (1959) employ Stewart and Grant’s typical gentle Hollywood personas, manipulated in a thrilling manner only Hitchcock can to captivate generations of audiences.

Hitchcock invented the original scream queen, Janet Leigh, in Psycho (1960), used spy-thrillers and murder to provide commentary on the impending WWII in his 1930s British era, and inspired his own successful Twilight Zone-like Alfred Hitchcock Presents ‘50s and ‘60s anthology television series. The imprints Hitchcock ingrained on Hollywood, and the entire film industry are vast, and one can only wonder how many more influential techniques, scenes, and tropes the director would have on his resume had he made all the films he set out for. That being said, here’s a breakdown of all the unmade Alfred Hitchcock movies that never made it beyond the pre-production stage.

Number 13 (1922)

Hitchcock’s solo directorial debut was 1925’s The Pleasure Garden, but it was very nearly the silent film Number 13, also known as Mrs. Peabody. The film would have chronicled residents of a low-income building owned by the American-founded Peabody Trust that was intended to provide affordable housing for London citizens. Alfred Hitchcock cast British silent actors Clare Greet and Ernest Thesiger were cast in the starring roles, though production was shut down after a few scenes had already been filmed when the movie’s budget fell through. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life of Light and Darkness states that Greet had offered to finance the film with her own money, which Hitchcock always remembered and inspired him to cast her in six of his later films.

Forbidden Territory (1933)

Early in Hitchcock’s transition into talkies, he intended to adapt British thriller novelist Dennis Wheatley’s 1933 novel The Forbidden Territory. Hitchcock and Wheatley were friendly, and the latter had visited his film sets numerous times, so when Wheatley’s novel was first published, he gave a copy to the director. Via Alfred Hitchcock’s London, Hitchcock was eager to adapt the story into a film, though he couldn’t secure the rights at the time since he was in the middle of moving to Lime Grove Studios under Michael Balcon. His new boss wasn’t keen on making the film, so he enticed a colleague moving to Britain to secure the rights for him. Hitchcock’s friend achieved Forbidden Territory’s movie rights, but Balcon wouldn’t release Hitchcock to direct it, so he moved on with his first version of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) instead.

Forbidden Territory would have fit in with Hitchcock’s spy thrillers of the 1930s, following an Englishman who ventures to the Soviet Union with a friend after receiving a coded letter from his missing American friend who is now held in prison. Since Hitchcock wasn’t allowed to direct the film, it went to American director Phil Rosen instead. Though Forbidden Territory was never directed under Hitchcock’s eye, it remained connected to him as the film’s screenplay was written by his wife and frequent collaborator Alma Reville.

Greenmantle (Early 1940s)

The 1916 John Buchan book, Greenmantle, is notorious for inventing what is known as today’s modern spy novel, which is a genre right up Hitchcock’s alley. An adaptation of Greenmantle would have been the natural progression for Hitchcock’s British-era spy films considering he was working on developing a film version between 1939 and 1942, only four years after his successful adaptation of another Richard Hannay novel, The 39 Steps.

Hitchcock (via The Alfred Hitchcock Encyclopedia by Stephen Whitty) apparently wanted Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant in the lead roles of Greenmantle, a pairing that would later be cemented in his masterpiece Notorious (1946). The film would have been a sequel to The 39 Steps, following Richard Hannay in an international spy plot during World War I. Hitchcock tried to secure the rights to the book but found that Buchan’s estate’s price was much too expensive. Considering the wide success of The 39 Steps, Greenmantle likely would have been remembered as another of Hitchcock’s greatest film adaptations.

Unnamed Titanic Movie (1939)

When Hitchcock intended to dive into the RMS Titanic disaster, the event was still young in the global consciousness at only about 27 years later. Hitchcock would have been the perfect director to blend the American and British cultures and shared tragedy from the event, but he also wouldn’t have had Titanic’s (1997) biggest sellers: Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio. One wonders what big-name actors Hitchcock would have employed to enhance the drama of the Titanic’s sinking, though Cary Grant seems like a probable name for the project’s timeline.

The unnamed RMS Titanic project was set to be Hitchcock’s first dive into Hollywood directing, whereas that title went to Rebecca (1940) instead. According to reports (via BFI), Hitchcock had traveled to America in 1939 to sign a contract with film producer David O. Selznick–who at the time was running Selznick International Pictures and distributing through United Artists–to direct a drama about the Titanic. Fellow reports (via HistoryExtra) claimed that British officials refused the film’s production, citing fears of making a maritime disaster film as World War II loomed near. Since Hitchcock and Selznick had already signed a contract, the two decided to make Rebecca instead, which would win the Best Picture Academy Award the following year.

Unnamed Nazi Documentary (1945)

Though Hitchcock never made a movie that explicitly involved World War II or named its primary players, his films of the 1930s and early 1940s carry messages that very obviously touch on the horrible situation in Europe and eventually in the United States. Several of Hitchcock’s British-era films from the ‘30s, like The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps, allude to international espionage, treason, and an immoral national enemy that hint at Europe’s crisis. The most overt World War II anti-Nazi film made by Hitchcock was Notorious which starred Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains, where the formers are spies that are trying to obtain secrets from the latter Nazi leader.

The unmade Nazi documentary that Hitchcock intended to direct would have been produced in 1945 toward the end of World War II. Hitchcock was recruited as a supervising director in which he would uncover Nazi crimes and concentration camps, including segments created by Allied military units from the United States, United Kingdom, and France, as well as the Soviet Union. Reports found (via BBC) that the British filmmakers decided it was no longer necessary to show Nazi atrocities to the German people, instead of focusing on repairing relationships with the country. The documentary was scrapped at the time, but Hitchcock’s footage has been reconstructed and shown in a recent documentary, Night Will Fall, that dives into the backstory and process of the unmade film.

Hamlet (late 1940s)

According to Cary Grant, the Making of a Hollywood Legend, Hitchcock pitched several ideas for future collaborations with Cary Grant while they were filming Notorious. One of the most promising ideas was a modernization of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Hitchcock wanted Grant in the titular role, reverting to an almost villainous persona Hitchcock had tapped into with Grant in Suspicion (1941).

Hitchcock’s Hamlet adaptation was scrapped soon after word of its production was given to the media once another writer claimed he already held the rights to a modernization of Hamlet. Hitchcock was apparently still adamant about making the film, though he abandoned it after years of an ongoing legal battle. Although Hitchcock and Grant never got to truly make a Hamlet film as they planned, there were plenty of Shakespearean allusions in North by Northwest to make up for it.

The Bramble Bush (early 1950s)

Around 1951, Hitchcock proposed adapting the 1948 David Duncan novel The Bramble Bush to the screen. The film would have involved a former Communist who accidentally adopts a murder suspect’s identity while on the run from American police. The director hired several writers to give spec scripts for the movie, but none lived up to his standards for a high-end Hitchcock thriller. He also scouted several locations around the United States for shooting but found that they would use up too much of his budget. Instead of moving forward with The Bramble Bush that proved difficult in pre-production, he decided to go ahead with Dial M for Murder (1954), starring frequent collaborator Grace Kelly.

No Bail for the Judge (1954-1959)

Another failed attempt at bringing a successful thriller novel to the big screen, Hitchcock tried to adapt the Henry Cecil novel about an English lawyer, assisted by a thief, who has to defend her father, a High Court judge, after he is accused of murdering a prostitute. One of the more notable nearly-made Hitchcock films, No Bail for the Judge, was set to star Audrey Hepburn as the lawyer along with actors Laurence Harvey and John Williams. The novel was extremely racy, and Paramount was hesitant to back its controversial subject matter while Hepburn was against filming a rape scene.

Claims (via Newsweek) suggested Hepburn and Paramount lobbied for Hitchcock to continue filming but omit the rape scene. However, Hitchcock refused, and the project was thrown out. Though a Hitchcock and Hepburn collaboration in the late 1950s likely would have been a blockbuster hit and elevated both of their careers, the scrapping of No Bail for the Judge allowed Hitchcock to move forward with arguably his biggest masterpiece, Psycho.

Flamingo Feather (1956)

It appears that Hitchcock tried to trade in his 1930s Nazi fear in Europe for a 1950s Communist red-scare in America after his transition to Hollywood. Possibly as a way to avoid being blacklisted by HUAC, Hitchcock became fascinated with using anti-communist plots in some of his unrealized projects. One of the most interesting unmade films of Hitchcock’s 1950s span was Flamingo Feather, a proposed adaptation of Laurens van der Post’s novel documenting a South African anthropologist who discovers communists in the area are enticing the Black population into rebellion.

Hitchcock (via BFI) had cast James Stewart as the lead-role adventurer and would be traveling to South Africa for filming. He also wanted Grace Kelly to reappear with Stewart as the romantic interest, while Paramount Studios was bragging about using over 50,000 extras. Stewart and Hitchcock had recently finished filming The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) in Morocco, so Hitchcock soon performed a research trip in Africa to scout locations. Hitchcock discovered filming in the area would be nearly impossible both physically and financially, so, along with hesitation about making such a politically charged film, decided to scrap Flamingo Feather altogether.

The Wreck of the Mary Deare (1959)

Though Hitchcock had been working with Paramount Studios for some time, MGM attempted to recruit the director to adapt Hammond Innes’ novel The Wreck of the Mary Deare with Gary Cooper and Burt Lancaster set to star. The movie would have seen Hitchcock out at sea, directing Cooper and Lancaster as two men who attempt to beach a rickety old ship and end up in a plot deeper than what they imagined. Hitchcock was eager to work with Gary Cooper, who had rejected starring roles in his films Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Saboteur (1942) but was hesitant about the subject matter.

Hitchcock commissioned Ernest Lehman to write a spec-script, though he would always talk about off-topic subjects every time the two men would meet about The Wreck of the Mary Deare. According to BFI, Lehman felt guilty that MGM Studios paid him for a courtroom scene he wrote even after Hitchcock dropped out, so he pitched a new film for the two men to work on together. Thankfully for the spy thriller genre, Cary Grant, and Hitchcock’s everlasting legacy, Lehman suggested they make one of the most memorable films in history, a project that would become North by Northwest.

The Blind Man (1960)

In an effort to one-up his own exquisite landmark-based plots like Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest and the French Riviera in To Catch a Thief (1955), Hitchcock intended to make another film with Ernest Lehman located at Disneyland. Hitchcock and Lehman crafted a story about a blind piano player, Jimmy Shearing, who regains sight after a corneal transplant from the eyes of a murder victim. While watching a Wild West show at Disneyland, Shearing has visions of the dead man’s murder and sees the murderer’s image is on his retinas. Hitchcock intended James Stewart to play the lead role with the plot culminating in a climactic chase scene aboard the RMS Queen Mary.

James Stewart (via BFI) apparently dropped out of the project, and Walt Disney rejected giving Hitchcock the rights to shoot at Disneyland after being abhorred by Psycho, so the project was unfortunately scrapped. Lehman wrote most of the script before he and Hitchcock decided not to move forward, so it was recently touched up, and The Blind Man became a 2015 BBC radio show drama starring Hugh Laurie.

Mary Rose (1964)

Reports (via BFI) also stated that Hitchcock wanted to adapt J.M. Barrie’s play Mary Rose after seeing it live in London in the early 1920s. The film would have detailed a woman who goes missing twice: once as a child for three weeks when visiting the Scottish coast, and once more when she visits the island again as an adult. Even when Hitchcock pitched the idea to Paramount Pictures and Century-Fox in the 1950s with Grace Kelly as the lead, the studios still weren’t keen on financing the project.

About a decade later, when Hitchcock was working on Marnie (1964) with screenwriter Jay Presson Allen, he commissioned her to write a similar story about a woman missing for 25 years after visiting a Scottish island. Hitchcock wanted to reteam with Tippi Hedren for the third time in the prospective project, but Universal Studios also rejected the idea on the grounds that audiences expect more horror elements out of a Hitchcock movie. Though the world will never be able to see a Hitchcock version, the time-travel sci-fi elements of the project seem to be a perfect venture for Christopher Nolan.

R.R.R.R. (1964-1965)

A passage in Hitchcock: Past and Future details an original project that Hitchcock had been eager to develop since 1935: R.R.R.R. This venture would have taken a different turn for Hitchcock that nears the later Clue craze involving a murder movie with comedic overtones. The film would be set in a New York City hotel (likely similar to 1932’s Grand Hotel) in which a family of Italian criminals is brought to America by a reformed relative and devise a plan to steal valuable coins that are estimated to be worth the top-rated value R.R.R.R.

Hitchcock worked with Italian screenwriters on drafting scripts for R.R.R.R. but cited the language barrier as the reason the men couldn’t come up with satisfactory material. After the failure of Marnie, Hitchcock had apparently tried to enter the European and especially Italian cinema direction of the 1960s with films like Bicycle Thief (1948) as inspiration. When Hitchcock realized he couldn’t get into the new wave of filmmaking, he moved on to Torn Curtain (1966), which was, unfortunately, another failure for the director.

Frenzy (Kaleidoscope) (1967-1968)

The late 1960s were a tough streak for Hitchcock with the failures of movies like Marnie and Torn Curtain (1966), though it wasn’t without trying from the master of suspense. One of Hitchcock’s final directed films about a London serial killer was called Frenzy (1972), though it is very different from the Frenzy (or Kaleidoscope) that he attempted to a few years prior. Frenzy was intended to be a prequel to his 1943 psychological thriller Shadow of a Doubt starring Joseph Cotten and Teresa Wright. Several scripts were written for Frenzy (Kaleidoscope), including one by Hitchcock himself and another with notes from French director Francois Truffaut, plus the film went through a significant portion of the development process before being swept aside.

The plot was inspired by real-life serial killers Neville Heath and John George Haigh, who terrorized England years earlier. The film would have detailed the Merry Widow Murderer played by Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt before the events in which he visits his family, where he is a young, handsome bodybuilder who murders young women. Similar to his niece attempting to catch him in Shadow of a Doubt, Frenzy would have seen New York police setting traps to catch him with a policewoman as bait. Hitchcock had already sketched out the three main murders he wanted to depict: one at a waterfall, another on a mothballed warship, and the final at an oil drum refinery.

Universal Studios quickly rejected the film due to its extremely dark and abhorrent imagery, feeling that he had gone too far, even for Hitchcock. There was apparently far too much sex and violence within the script that seemed unusual when compared to his prior work and excessively shocking for the horror bits expected of Hitchcock. Hitchcock was extremely disappointed in Frenzy‘s rejection considering big names like Robert Redford were already rumored for the lead, and he now realized he didn’t have complete freedom to make whatever he desires.

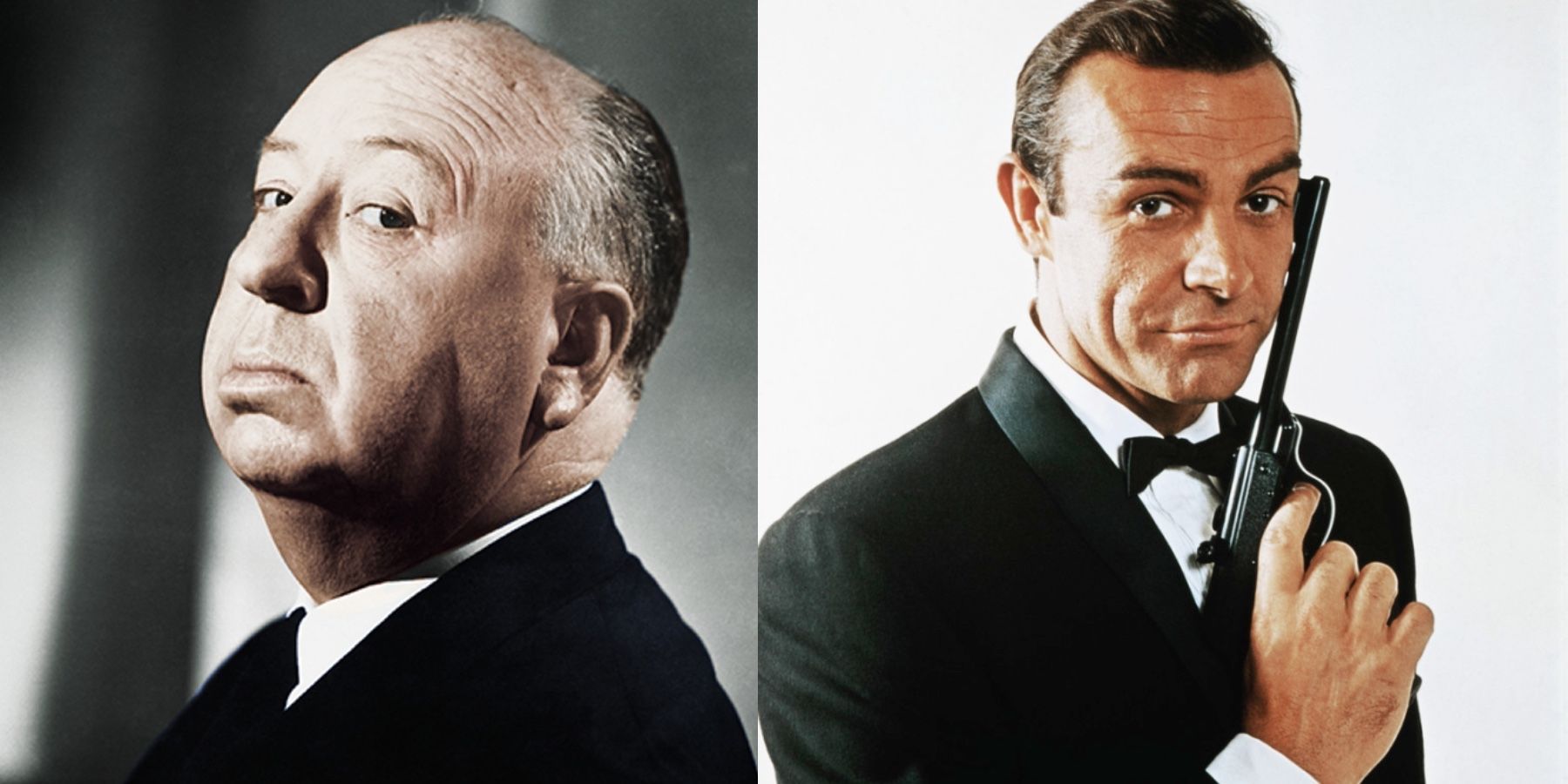

The Short Night (Late 1970s)

The Short Night was Hitchcock’s final attempt to make his own James Bond film which he had tried with Torn Curtain and Topaz, though it was odd that Hitchcock didn’t realize North by Northwest already was his Bond movie. This project would have told the story of a British double agent that escapes prison to find his wife and children, while an American agent who tries to stop him falls in love with his wife. The film is one of Hitchcock’s biggest casting what-ifs, with James Bond himself, Sean Connery and Clint Eastwood, pegged for the leads and Walter Matthau as the villain.

Hitchcock went through several prior-collaborator screenwriters to write scripts, though he had falling outs with each one. The last screenwriter worries that Hitchcock’s failing health meant the movie would never get made, so Hitchcock fired him and attempted to write it himself. According to BFI, Alfred Hitchcock finally realized his health was deteriorating, decided to scrap the project and go into retirement in 1979 instead.