A film about coming of age in the US as a first-generation teenager, Dìdi (弟弟) made its Texas debut at the 2024 South by Southwest Festival. The film marked the second year in a row the festival featured a premiere by Writer and Director Sean Wang, who won the 2023 SXSW Short Documentary Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award for his Academy Award Nominated Short, Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó. Though the film drew from Wang’s own childhood as the child of Taiwanese immigrants, but held back from telling a true memoir. Dìdi (弟弟) marks Wang’s feature directorial debut, and stars Izaac Wang, Joan Chen, and Shirley Chen.

Set in 2008, Chris Wang (Izaac Wang, Raya and the Last Dragon) is a 13-year-old boy living through the last summer before he enters the chaotic world of American High School. In this time of change, Chris will navigate a world where he is made to feel unworthy, while on the sometimes joyful and sometimes painful road through adolescence. He must learn lessons his parents can’t teach him like how to flirt, how to skate, and how to love your mother.

![Dìdi Director Sean Wang On His Semi-Autobiographical Tale Of Adolescence & Motherly Love [SXSW]](https://static1.srcdn.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Best-Coming-Of-Age-Movies-People-Of-Color.jpg)

Related

10 Best Coming-Of-Age Movies Starring People Of Color, Ranked By Rotten Tomatoes

Coming-of-age is a popular genre, yet movies centering on characters of color don’t receive as much recognition. Rotten Tomatoes ranks the best here.

Screen Rant interviewed Sean Wang at the 2024 SXSW Festival just after Dìdi (弟弟) found distribution with Focus Features. He talked about the broad strokes of his own childhood that informed the story behind the film, and the crazy ride he’s been on since Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó debuted at the 2023 SXSW Festival.

Dìdi’s Journey From Sean Wang’s Mind To The Screen

Screen Rant: Sean, congrats on Dìdi. I saw this film last week in Los Angeles. It is such a special film. It is so sweet and soulful and nostalgic, and you can just tell it was made with so much love. And what a year you’ve had. January, you’re at Sundance with Dìdi and get nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary Short. Has this year been a whirlwind for you?

Sean Wang: Yeah, we premiered the movie on a Friday, then got nominated for an Oscar on a Tuesday. The next Friday we won the Audience Award, Special Jury prize for Ensemble Cast. I think Saturday, Focus bought the movie, and then Sunday, I was back in LA in my room like, “What just happened?”

I think the lion’s share of your work has been in the documentary realm and shorts. This is, I believe, your narrative feature film debut. What was the process of bringing this to the screen?

Sean Wang: It was long, but you hear people and filmmakers say, “Oh, this film took seven years, a decade long, to make,” or something. I think we kind of fall in that category, but it wasn’t like I was only working on this for the last seven years. I started probably writing this in 2017 around. And so it was that, it was just always chipping away at this script, thinking, “Oh, hopefully someone will let me make this one day.” And it was personal and I wrote it in a way where I was like, “Okay, I think it’s small enough. It’s set in my hometown. We can bring the community into it.”

But even just looking back now in retrospect, a lot of the shorts came from what I was trying to explore in the future too. I think a lot of my shorts also explore themes of belonging and identity and friendship and adolescence as well. And so everything I’ve done in the last seven years feels all like they swirl together, even though this is a narrative feature, and a lot of the shorts, like you said, are doc shorts. To me, they all feel like they’re cut from the same cloth, and so I think they’ve informed one another.

Dìdi follows a 13-year-old Taiwanese American boy named Chris Wang, who’s struggling with early teendom. He’s struggling with how to connect with his friends and be a cooler kid, the typical, American struggle so many teenagers go through. How to talk to girls. How autobiographical was this story? Was this ripped from your own experience as a teen?

Sean Wang: I think people will watch it and think it is, and the broad strokes of it are. Obviously, I was 13 in 2008. I come from a Taiwanese American background. Both my parents are immigrants from Taiwan. I have an older sister, it’s the same age gap.

But ultimately, I wasn’t interested in making a memoir. If we look at the canon of personal storytelling and film, I think we’re probably closer to the ethos of a film like Beginners or 20th Century Women or Ladybird, rather than Fablemans. It was really just being inspired by movies like that. Movies like Ladybird or 400 Blows or Rat Catcher, movies that you could tell were so personal and lived in and vivid. The details and the texture were all there, but ultimately they’re telling a story. I think that’s what I was interested in. The world that I grew up in, that sort of hub of Fremont, California in the Bay Area, and the specificity of me and my friends, and watching a movie like Stand By Me and being like, “Oh, I relate to that movie, but it’s not my life.” And realizing, “Oh, the world I know, all those textures, all those details, I haven’t seen that in the movies that I love.” I think there’s something to mine there.

But ultimately I wasn’t interested in just splattering memories on screen, ultimately I was interested in telling a story, and I think it was going back to process. It was a bit twofold. It was like, okay, well, here’s all these memories. Here’s all these details that I think are so lived-in, are so vivid. That’s great; that all feels so personal. How do we then change that, modify that, adjust that? How do we combine characters? What is the story that we’re telling? I think our story is about, like you said, a 13-year-old boy, but also how he wrestles with shame and identity and belonging in this time period of the late 2000s.

Once we realized that’s the theme of the movie, it’s like the different ways that shame manifests itself in a young boy’s life, a young Asian American boy’s life during that time, whether it’s societal shame, cultural shame, personal shame. Then it was taking all of the things that were autobiographical and just seeing what we could do to modify all of that to serve the story.

Writing (And Finding) The Perfectly Imperfect Lead For Dìdi (弟弟)

I think another thing that’s really admirable about the film and this story is how imperfect Chris is. Was there ever any temptation to steer him into a more likable lane? Again, not that he’s unlikable, but he’s just imperfect.

Sean Wang: He’s a brat. He sucked. [Laughs] Not personally. I think even going back to the ethos of this movie, I wanted to make a movie that, again, had imperfect characters. I wanted to see a messy portrait of an adolescent kid. And I think a messy portrait is an honest portrait. Again, going back to movies like 400 Blows or Stand By Me, I think the kids in those movies, they feel like real kids. They’re loud and crass and they’re not perfect, they’re not always correct, but they’re also complicated and vulnerable and emotional. And I think that, to me, is what boyhood is, that’s what adolescence is.

And so I think you’re right, he is unlikable in ways. He’s unlikable because he’s figuring himself out, as we all are. And I think, to me at least, there’s a relatability and a charm in that he’s not just purposefully … He’s trying to figure it out, and that’s what makes him fumble and fall and make those mistakes.

I certainly got notes and sometimes like, “Oh, what if,” blah, blah, “he got a win here and there.” And it’s like sometimes he does, but I do think it was always about making it more honest and truthful to the moment than it was like, “Let’s have him pet a dog so he can be likable.”

We’ve got to talk, of course, about your young lead, Izaac Wang. I mean, what sort of search was it to find him? How many actors did you audition? How did you ultimately land on Izaac?

Sean Wang: Izaac was interesting because he was one of the first actors that we saw, and he had worked with my producer, Carlos Lopez Estrada on Raya and the Last Dragon a few years ago. I think he was 14 when we shot the movie. And being 14 is so different from being 10. And Raya and the Last Dragon is such a different movie than our movie. And so I had only seen him in those kind of roles. But the first Zoom that we had with him, I was like, “Oh, there’s something special here, but let’s just flip every stone.”

We went the street casting route, knowing that the character needs to skate, the character needs to speak Chinese, the character needs to also be a real kid, but also he needs to carry an entire movie on his back. And so we really read with Izaac for months and months and months, but knowing that he had this sort of magic to him, and it was all over Zoom. And one of the good fortunes that I had with this movie was I got to take it to the Sundance Directors Lab. And what they do there is you get to basically bring actors and workshop scenes from your movie that you find challenging physically.

I got to bring Izaac and Shirley, who plays Vivian in the movie. It was essentially the rehearsal that we never got to have on this movie. And getting to work with him there, it was just like, “This is it.” Yeah.

The Mother-Son Relationship Is At The Center Of Dìdi (弟弟)

And then we have to talk about the mother-son dynamic at the heart, because it really it is ultimately the heart of this film. And what a performance by Joan Chen, by the way. Can you talk about that aspect and how captured that dynamic between mother and son?

Sean Wang: Thank you. I really went back to that idea of wanting to create an honest portrait. I think we’ve seen a lot of mother-daughter relationships, but I wanted to try to make something that honored the relationship that I have with my mom and that honored the relationship that I think a lot of immigrant kids have with their parents, where it’s so loaded with love, but also this specific type of shame that you can’t really understand at that age, which is that gap, that cultural chasm of the immigrant experience. And wanting to explore that in a way that really felt honest, but ultimately end it with a warm hug.

And it is a loving, tender relationship, but it is complicated. And I think wanting to showcase the side of, especially Asian immigrant moms, that I felt like I hadn’t really seen in storytelling. These moms that were creative and artistic and sympathetic and empathetic and tender. I think the mom in our movie is very much not a tiger mom that we’ve often seen in portrayals of Asian mothers, and how that influences their relationship as well.

That was when the movie really clicked for me, at least when I was writing it, I was like, “Oh, that’s what this movie is.” It wants to be Stand By Me, [but] the secret heartbeat of the movie is the mother-son relationship. It was like, “Oh, how do we make a movie that’s a love letter to immigrant moms, but hidden in this movie about adolescent friendships and belonging?”

Has your mom seen the movie?

Sean Wang: She was giving notes on the script. I mean, she’s really proud of it. And she didn’t really give notes on the final cut, but definitely on the script. Even when we were editing, she was like, “Send me stuff.” I remember growing up, or not … But in the last few years, sometimes she would be like, “What are you working on?” She’s like, “Send it to me. Send it to me. I want to see.” I’m like, “Okay, but it’s a rough cut. Don’t give me any notes.” And then she’ll just write a bunch of notes. She’s like, “This doesn’t make sense.” I’m just like, “Okay. I didn’t ask her notes.”

But she has such an intuitive soul when it comes to this stuff. And even if she watches something and it doesn’t make sense to her because she doesn’t have the sort of cultural understanding, she knows how something makes her feel. And so I’ll send her a piece of music, for example. A lot of times when we’re working on the music for films, I’ll send her a piece of music and I just won’t say anything. I’ll be like, “How does this make you feel?” And she’ll be like, “It reminds me of a meadow on a sunny spring day.” And I’m like, “Okay. So I think that’s what we’re going for.” I can always trust her gut.

Recreating The Childhood Nostalgia For Dìdi (弟弟)

I also love how evocative it is in terms of, and nostalgic, I should say, for technology in the mid-2000s, and the way it’s executed on screen, it’s so perfect. But from just finding the perfect response to the girl he has a crush on and workshopping it in real-time with AIM and MySpace Top 8, and the sort of horrors of discovering where you do or don’t sit. Because something that really jumps out about the film is how you actually portray that technology.

Sean Wang: Thank you. Yeah, I’m really proud of those screen scenes. I think it goes back to … It was two things. It was, again, once I realized, okay, this is a movie that’s about a 13-year-old boy. Then it was, how do we make this more and more and more specific every step of the way?

And when I was like, okay, well, this is going to take place in the late 2000s, there was so much technology of the late 2000s that I felt like in the movies that were made during that time, they never got the technology right because I think by the time we actually learned how to integrate our screens with our stories, the technology had completely changed. By the time films like Noa came out, that short film that takes place entirely on screens, it was like we were already in this different language of technology.

Then I had worked at this team at Google for a few years called Creative Lab, and what I was doing there was learning how to tell stories on screens. A lot of their things took place on the devices we use every day, not unlike Searching, directed by Aneesh Chaganty, who’s a good friend. We had the same education, he used to work there too. And I remember when Searching came out I was like, “Oh, he just did the best version of that movie,” but I was already developing this movie.

That’s kind of when the screen stuff came into play, when I was like, yeah, there is a version of this movie that I haven’t seen because they never integrate technology. And what you were saying about how oftentimes I think when filmmakers cut to a screen or try to integrate technology, it never feels authentic. It never feels good. It never feels like, “Oh, that’s the screen I know and use in my everyday life.”

That was the bet that we were taking, was I think we can look back at this era and try to integrate all the screens and the technology of that time in a way that feels like I think how the internet was used, which was not this hacker music type thing. It feels mundane and grounded and intimate, but also very high stakes. Like when you’re talking to your crush, what does it feel like to have butterflies talking to your crush at 10:00 PM at night? And trying to capture those feelings in a way that feels as high stakes as it is, but really you’re just sitting in your room, quietly.

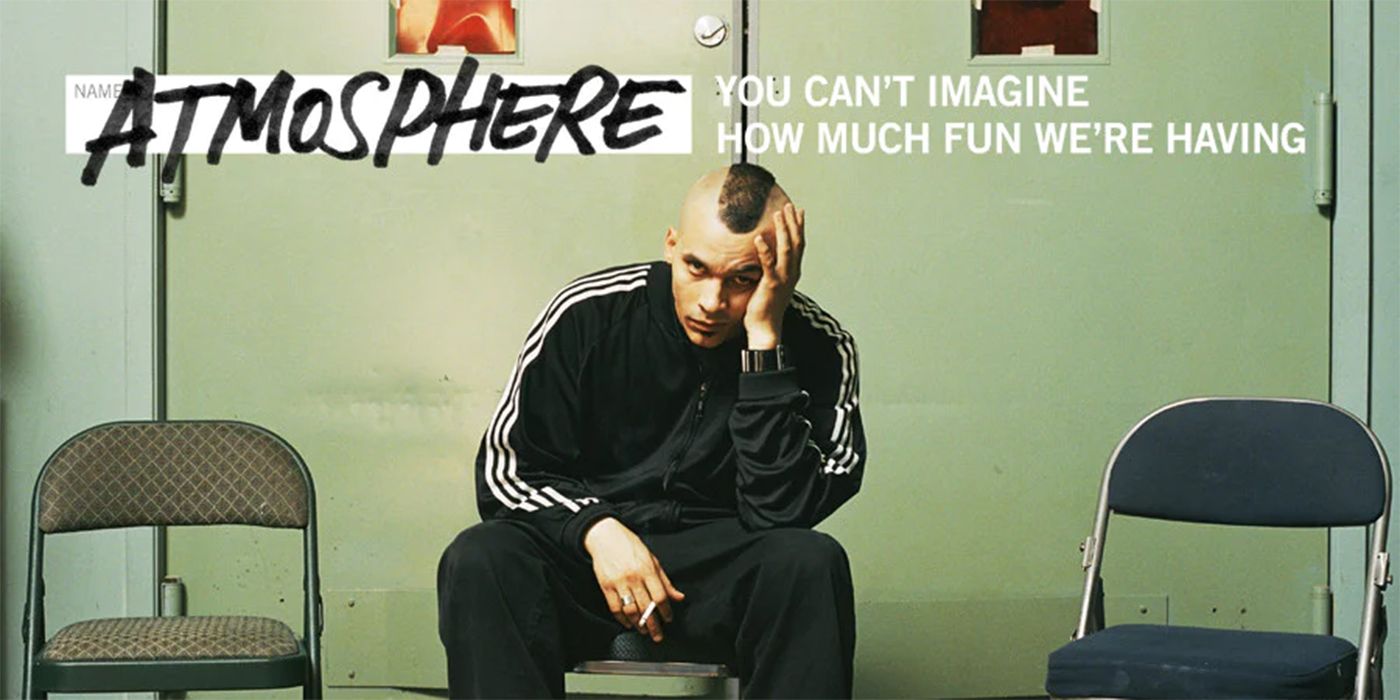

Speaking of the music, I love the soundtrack. You’ve got Atmosphere on there, and I’m a big underground hip-hop fan. How did you go about curating the soundtrack for this one?

Sean Wang: Yeah, I love the Atmosphere shout-out. We have a couple of Atmosphere needle drops in there, but it really went back to both hyper-specificity and the personal element. I think when we were like, okay, it’s going to be set in the late 2000s, I didn’t want the soundtrack of our movie to be songs that were already in the movies of late 2000s. One, because yeah, it’s like it’s been done. And two, we probably can’t afford it to have like M.I.A. or MGMT on our soundtrack.

Even before we started shooting the movie for years and years, I had a playlist that I would just add to. Half of the movie soundtrack is pulled from that playlist, and now I’m just so lucky that we were able to get those songs. A shout-out, Toko Nagata, our music supervisor.

But a lot of it was also curated in the sense that it didn’t have to necessarily be music that came out during the year of our movie, it just had to be music that felt personal to me. Atmosphere was a big artist in my life. A lot of the characters also in the movie have different kinds of influences. I was really influenced by pop punk and that kind of world growing up, but I had a lot of friends who were also influenced by hip hop, like Atmosphere, Blue Scholars, like Hieroglyphics, also from the Bay Area.

It was like, “How do we create a soundtrack that feels like the world that we’re in? And the world and the influence of the movie are so wide. It’s hip hop, it’s Bay Area, hyphy music, it’s skateboarding, it’s Warped Tour music. And so it’s like, how do we use music in that way to kind of reflect the world that the movie takes place in?

It wasn’t about the most high-profile song or the most high-profile artist, it was really more about, “Oh, does this song mean something to me?” And it could have been a song from a really small artist that no one really knew, but if I had something that had a beating heart underneath, it was like, “Oh, we should try and lean that way.” Go personal instead of recognizable. And then hopefully, if the movie does well, the song then becomes recognizable.