The detective movie has been around for the longest time, and the genre’s staying power could be traced all the way back to Chinatown. Originally released in 1974, Chinatown has since gone down in history not only as one of the greatest detective stories ever told but as one of the best movies ever made.

Chinatown is so good that it was able to withstand being tainted by its director’s infamy but it also continues to inform the way detective tales are told today, whether they’re modernized or not. Here are 10 reasons why Chinatown is the greatest Film Noir of all time.

Jerry Goldsmith’s Soundtrack

One of the most memorable elements of Chinatown is its soundtrack, which echoes the classic Noirs of the past. Composed by none other than Jerry Goldsmith, the movie’s haunting score is an integral part of the viewing experience that only adds more emotion to the most powerful scenes.

What’s even more impressive about this score is the fact that it was made in just ten days. Originally, Chinatown was composed by Phillip Lambro but his work didn’t go over well during some test screenings. Goldsmith was quickly chosen as Lambro’s replacement, and his rush-job ended up becoming one of his most memorable works.

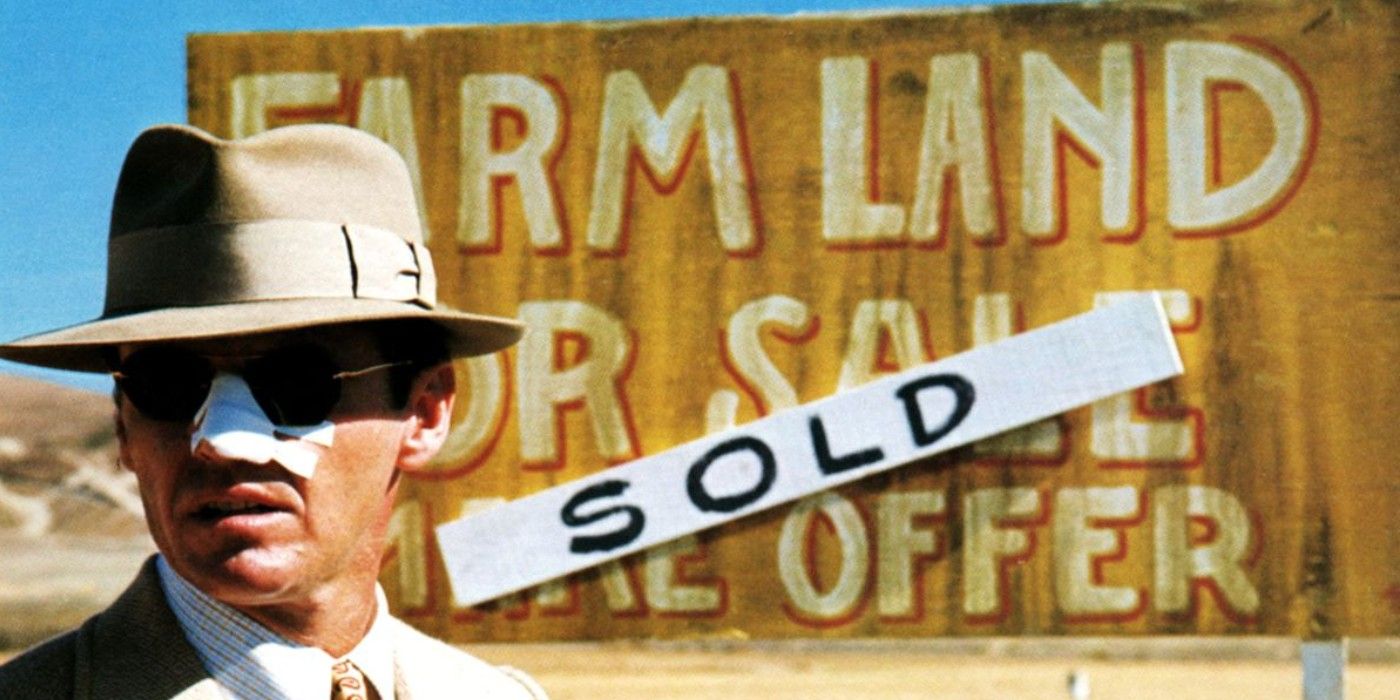

The Unorthodox Setting

Unlike many detective movies before it, Chinatown takes place in the sunny and sandy streets of Los Angeles. While this may seem a bit mundane by today’s standards, this was a pretty titanic shift back in the day.

The unspoken rule among detective movies of the time was that they always took place in some city’s grimy underbelly. Meanwhile, Chinatown not only proved that a desert town could be just as seedy as the Manhattan of Sweet Smell Of Success, but that the Noir story can be applied just about anywhere under the right circumstances and tweaks. This didn’t just change the visual language but the subtleties as well, making Chinatown unique among its contemporaries.

John Huston As Noah Cross

It’s practically a genre tradition to have a corrupt politician or business mogul at the center of the conspiracy, but none are as vile and despicable as Noah Cross. Not only did he kill some business rivals to monopolize Los Angeles’ water supply, but he also fathered his own granddaughter after having an incestuous relationship with his daughter.

Of the many corrupt businessmen to populate the genre, Cross stands as the one to beat. Everything he stands for is a great representation of just how much power can corrupt one person and everyone in their vicinity. Huston’s deep voice only made Cross more imposing than he already was.

Faye Dunaway As Evelyn Cross

Upon first glance, Evelyn Cross may look like the usual damsel in distress for the detective to save or the femme fatale he has to be wary of. While Evelyn has shades of both, in the end she reveals herself to be a tragic figure and victim who’s at the mercy of an immoral world.

Faye Dunaway was able to bring Evelyn – a woman who has to bear years’ worth of trauma and domestic abuse at the hands of an evil man – to convincing life, where her subtlest of body language spoke volumes about how much pain she’s hiding.

Jack Nicholson As JJ “Jake” Gittes

When it comes to cinematic private eyes, none could be more iconic than Jake Gittes. While he’s obviously not the genre’s first sleuth, Gittes became an entire generation’s default hardboiled detective to emulate in their works.

Jack Nicholson’s performance (and writing) helped make Gittes more than just another stereotypical detective, instead of transforming him into a classic Noir detective who also has his own tragic past informing his world-weary present. To preserve Gittes’ impact, Nicholson never portrayed another detective onscreen. He did, however, reprise the role for The Two Jakes.

The Script Is Pretty Much Perfect

Aside from the famous line about the eponymous location (you know the one), Chinatown is loaded with quotable quotes that only use a few words to deliver one hell of a suckerpunch. Not only that, but the central mystery and everything that happens in between is airtight, with nary a plot hole in sight.

This is because Robert Towne’s script is as close to perfection as screenwriting can get. To this day, his script for Chinatown is used in film classes to teach foreshadowing, structure, symbolism, and more. It’s worth noting that Chinatown was nominated for 11 Oscars but only won the one for Original Screenplay.

The Subtle Way The Mystery Unfolds

A common practice in older detective movies was to have a narrator or to give the focal private eye a lot of monologues for the audiences’ sake. This was done for exposition’s sake and while it was appropriate back then, it can come off as tedious or on-the-nose today. Chinatown, on the other hand, chose to handle its investigations silently, letting audiences unravel the mystery while Gittes does.

Chinatown trusts that its viewers are just as observant as Gittes is, thus making the experience of cracking the case more organic and immersive. The audience only knows as much as Gittes does at any given time, making each twist as shocking as it needs to be. This use of “Show, Don’t Tell” set a precedent going forward, to the point where sharp viewers tend to solve the mystery way ahead of the onscreen investigator.

The Tragic Ending

Chinatown is best known for its heartbreaking ending, where Evelyn dies, Gittes is left broken, and Cross gets away. While depressing endings are common today, Chinatown’s came out in a time when detective movies usually ended happily. This risky creative decision paid off well, as it’s considered to be one of the best endings ever seen.

What makes it more interesting is that this wasn’t the original ending. To play up the homage to bittersweet Film Noirs, Towne had Evelyn kill Cross and go to jail as a result. Polanski, who was processing his own personal tragedy, came up with the famous darker ending. The two parted ways after this disagreement, but Towne later conceded that Polanski’s version was better.

Chinatown Solidified The Neo-Noir

Chinatown is obviously not the first Neo-Noir of its time, but it’s undoubtedly the most important one. While gritty detective movies were pretty common in the ‘70s, few were made in the style of The Maltese Falcon and its ilk. At the time, these movies were often criticized for prioritizing violence over the actual mystery, with many filmmakers excitedly taking advantage of the recently loosened censorship rules but forgetting everything else by accident.

It wasn’t until Chinatown that the genre’s legitimization really took hold, which elevated the pulpy thriller to arthouse heights. Many imitated Gittes’ tragedy but failed to replicate the success. To this day, Chinatown’s influence can still be felt in modern Neo Noirs. This is seen in movies, TV shows, and even video games, with many considering L.A. Noire to be Rockstar’s unofficial Chinatown remake.

Chinatown Is The Culmination Of The Entire Film Noir Genre

Chinatown may bear the hallmarks of a classic Film Noir but technically speaking, it’s a Neo-Noir. Simply put, Neo-Noirs were a revival of the classic Film Noirs of the ‘40s and ‘50s. During the resurgence’s early days, most of its examples were modernizations (ex. Dirty Harry and The Long Goodbye), with Chinatown being the rare period piece.

By following the classic mold and improving upon the Noir’s foundations, Chinatown not only proves to be a good homage to the old genre but also becomes its belated peak. Chinatown pays tribute to its past while also elevating every single trope and convention that defined the genre, making it the quintessential Film Noir every film buff and/or aspiring filmmaker needs to see at least once.

For lack of better words, Chinatown is Film Noir at its peak and there’s a reason why no movie has been able to dethrone even decades after its release.