Warning: contains spoilers for Berserk below

What is the purpose of fiction? Since the postmodern age, avant-garde storytelling has often been consumed with the idea of “deconstructing” popular tropes and archetypes, a practice in which the writer attempts to portray logical fallacies within the existent conventions of the genre or media they are operating in, in order to depict greater inadequacies and truths related to the values of our society and culture. The seminal example in comics would be the work of Alan Moore, most known for the maxi-series Watchmen, often credited with changing the landscape of the medium. However, perhaps the best example of an honest depiction of why conventional tropes of heroism can be so harmful is found in Kentaro Miura’s Berserk, and the gradually unfurling tale of its three principle characters, Casca, Griffith and Guts.

Since his debut in 1989, Miura has been hard at work crafting one of the darkest manga stories ever, of the former mercenary-turned wandering warrior named Guts fighting a never-ending battle against an army of countless demons at the command of the man who nearly murdered him, his former friend Griffith. Much of this epic has been concerned with the recovery of his one-time lover (and Griffith’s former second-in-command) Casca’s sanity, having been lost during “The Eclipse”, an episode early on which resulted in Guts’ entire mercenary company being wiped out in the name of furnishing the maimed Griffith with a sacrifice worthy of turning him into a godlike being.

While superficially this story can be read as a cynical affirmation of common heroic fantasy tropes, the brooding, yet noble warrior on a quest to save a helpless damsel and defeat a duplicitous villain, in fact, one of the key factors in what makes Berserk such a resonant and enduring tale is how it clearly demonstrates the danger of these tropes and their harmful nature when employed en masse across the cultural landscape.

To amplify this critique, Miura uses one of our most ancient and traditional genres: fantasy. Arising out of religious stories, old epic poems, and fairy-tales, fantasy as a genre is a conundrum in our modern age in that while it theoretically allows for the most outlandish and imaginative stories in the field of fiction, it has always been somewhat restrained by its traditional tropes. A swordsman fighting monsters, an evil empire toppled by an army of brave warriors, immortal wizards with magical powers dueling in a classic battle of good vs evil; since the days when Tolkien first published his seminal epic The Lord of the Rings, the genre of fantasy hasn’t changed much. It is through discussion of these tropes, as his three chief characters embody them, that Miura demonstrates why this stagnation in the form of recurrent tropes is so harmful and stifling to storytelling as a whole. And, likewise, he offers a compelling solution to these questions.

First, Guts, the traditional brooding hero who occupies a similar role to characters such as Aragorn and Achilles. Initially introduced as a dark, somewhat amoral monster killer with a giant sword, slasher smile, and an obsession with hunting demons, it becomes evident as the story goes on that his world is infested with monsters that are capable of unfathomable cruelty and despotism and he may be the only human alive capable of putting an end to them. Despite this heroic impetus behind the character, he remains a constant source of disgust, revulsion and horror for much of the story, willing to commit truly despicable acts in the name of seeing his quarries brought down. It is only far into the story that he gradually begins to settle down and become a more grounded, relatable, but still an often unpredictable character.

On closer inspection it becomes quite apparent why this is: Guts has spent the majority of his life as a beleaguered and sometimes abused pawn of heartless military commanders, and, even once free of them, spends most of his time either training or simply fighting the demonic forces which seek to take him as a sacrifice. Despite everything that’s happened to him, he is still the strong warrior, capable of fighting the kinds of monsters that no other living human could possibly emerge victorious over, but this is because it is simply all he has in his life. Nothing else exists for him except the eradication of evil. In some ways, this is a more realistic portrayal of what a true dragon-slaying hero of folktales would be like if such a person were real: they would be a single-minded brute who spends every moment preparing for their next battle because that would be the only way they could possibly survive such a crucible.

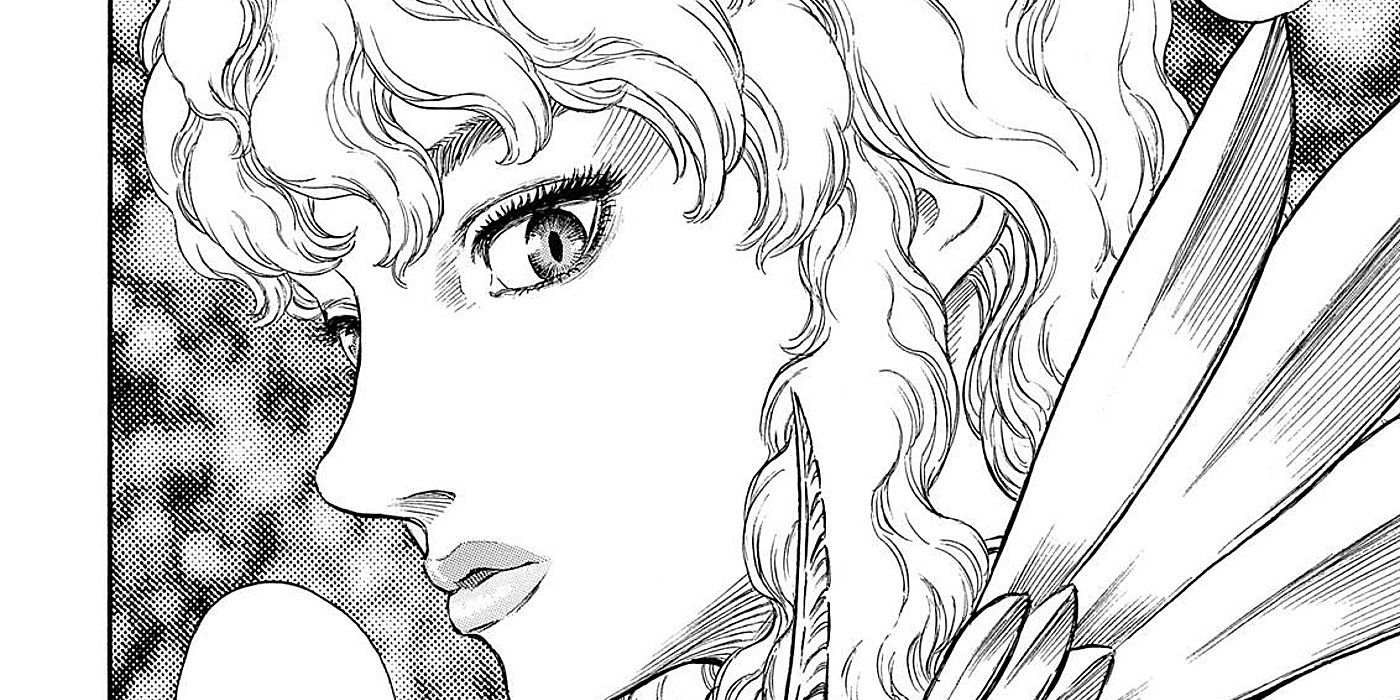

Likewise, the character of Griffith embodies another convention of popular myth revealed as dangerous; that of the “prophesied hero”. After finding an egg-shaped pendant, or behelit, known as “The Egg of the King” as a child, Griffith embarks on a quest to become king himself, believing it his mission and destiny to do so. Rising from humble origins, Griffith becomes commander of the most powerful mercenary band in the Kingdom of Midland, The Band of the Hawk, and reveals himself as a ruthless and cunning leader who would seemingly stop at nothing to attain his goal. While much loved by his men, Griffith time and time again demonstrates that, despite their love, he actually views them as little more than stepping stones which he, by right, can sacrifice if it means putting him a step closer to his goal.

Ultimately, Griffith does sacrifice his men, quite literally, so that he might attain godhood, and in the process is transformed into a godlike demonic being. In doing so, he is symbolic of why this idea of being a prophesied savior is such a harmful one: because he believes his mission is validated by a greater, divine force, Griffith feels he has no need to exercise moral-ethical behavior in his choices throughout his life, as such concerns are beneath him when it comes to attaining his goal. Even when his status as a prophesied savior turns him into a hellish, compassionless monster capable of unimaginable violent cruelty, he still believes himself to be the angelic savior he dreamt he would become because, as a prophesied “savior”, he no longer sees the difference between genuine kindness and emotional manipulation.

Finally, and perhaps most tragically, the character of Casca demonstrates the harmfulness of the common trope of the strong-willed, dependable warrior woman. For much of the story, Casca is relegated to a literally speechless and helpless damsel, having been so traumatized during her assault by Griffith during The Eclipse that her mind is literally broken, reduced to the level of an infant. This Casca is constantly compared to her former self: a no-nonsense battle commander and capable swordswoman who disdains Guts’ singlemindedness and follows Griffith’s lead out of respect and admiration. When Griffith is captured and the Band of the Hawk left leaderless, Casca steps up and keeps the mercenaries alive and together, united by their devotion to Casca’s compassionate yet strong leadership. Sadly, this ends up resulting in their collective deaths after rescuing Griffith during “The Eclipse”, culminating in Casca being horrifically sexually assaulted by Griffith with the aid of his demons.

What Miura seems to be alluding to in his characterization of Casca is the danger of this trope in fiction where strong women are idolized, in some respects fetishized, and subsequently made targets of simply for having positive qualities like strength, devotion, and faithfulness. What happens to Casca is categorically not fair, serving as a constant reminder of the depravity Griffith is capable of, and some might call it borderline sexist. However, what Casca actually represents is a warning: that it is not right to use strong women in fiction as an idea simply to be attacked. Casca is not attacked because she is a delicate flower of a woman, Griffith chose her as a victim literally because she was such a loyal friend and valiant comrade. In reality, this is often why people are victimized, because of the perpetrator’s sadistic urge to demean an otherwise perfectly exemplary, attractive, and strong-willed person. And this plays itself out over and over again in fiction because it is so accepted.

The story of Berserk is a twisted, harrowing, and revelatory journey through the darkest recesses of the human heart, and includes some great fantasy-action as well. But what makes it great is that, on a deeper level, Miura is trying to demonstrate how the conventional tropes of our stories can be harmful, and spread harmful perspectives if left unchecked and unquestioned.