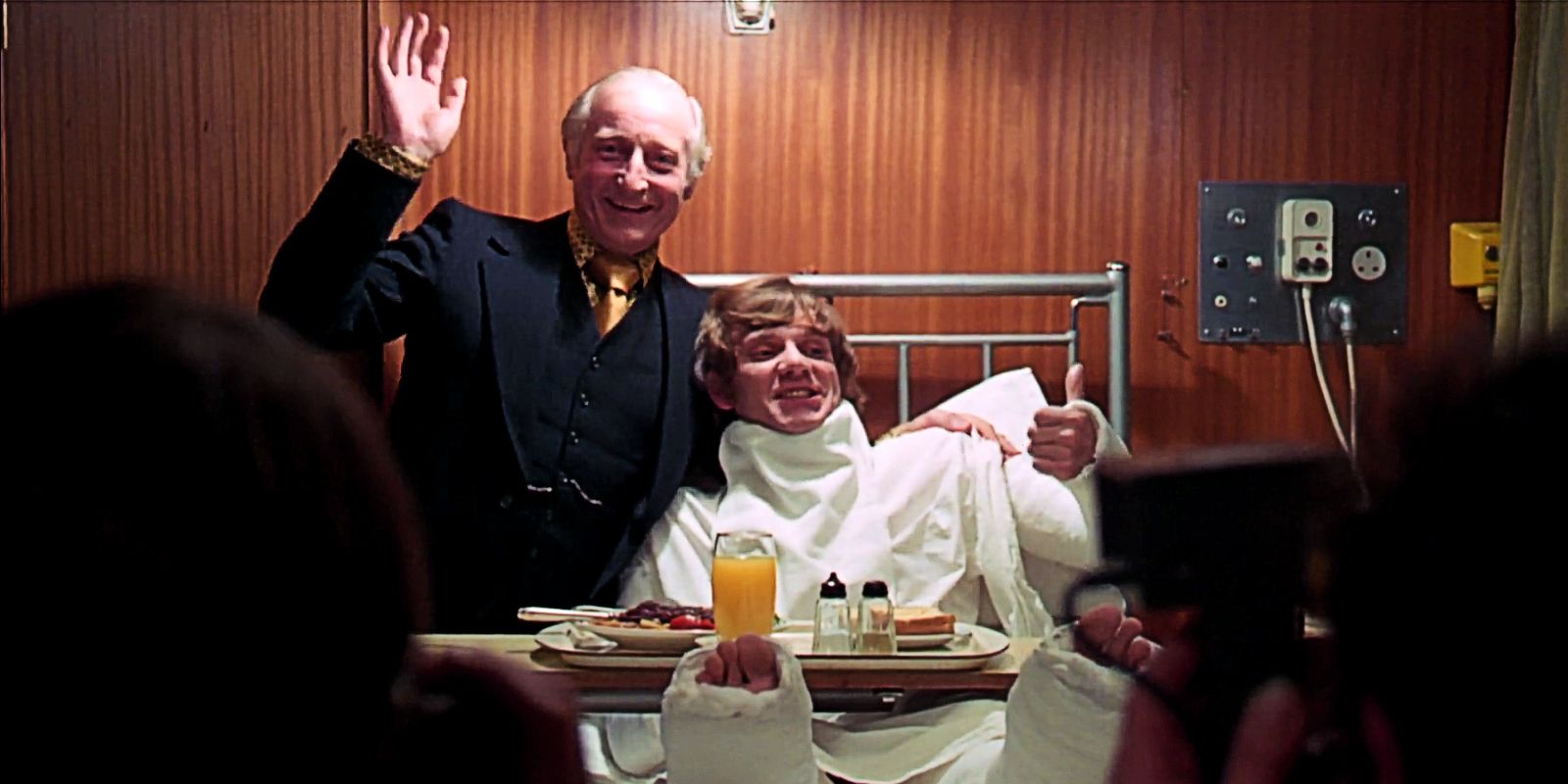

What is the significance of the ending of Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 dystopian horror, A Clockwork Orange? Based on the eponymous novel by Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange is a cause célèbre, capturing a depraved monologue in a spiritual wasteland set in the future, along with unsettling violence and satirical humor that aim to overwhelm the senses. The movie is now currently available for viewing on Netflix.

In order to understand the ending of A Clockwork Orange, one needs to look into the relationship between Burgess’ novel and Stanley Kubrick’s movie adaptation. The film eclipses Burgess’ true novelistic intentions, as it omits the 21st chapter, which is considered integral to Alex DeLarge’s character redemption and assimilation into accepted norms in society. However, the film’s bleak and complex ending has been accepted by audiences as the more authentic one, as many consider Burgess’ resolution to be unconvincing and inconsistent with the style and intent of the book.

In essence, A Clockwork Orange takes a deep dive into the ethical and moral ambiguities posited by the question of choice and free will. Right from the inception of the narrative, Alex (Malcolm McDowell) is largely predisposed to drugs, anarchy, and “ultraviolence,” and is a criminal who operates outside of the fringes of accepted society. This grants him considerable thrill, which slowly starts to eat at him during his rehabilitation program that involved psychological torture, along with coercion of a morally dubious nature. The seminal question that is raised here is: Is Alex, with his penchant for sexual and moral depravity, truer to his humanity as opposed to when he is seemingly reformed by the forced conditioning of the Ludovico treatment? Here’s the ending of A Clockwork Orange, explained.

What Does Alex Represent In A Clockwork Orange?

In the dystopian world of A Clockwork Orange, juvenile violence emerges as a major social deterrent, wherein Alex is a prime example of this kind of behavior. Akin to most teenagers within this setting, Alex speaks in the hybrid slang of the times, Nadsat, dresses in the “heighth of fashion,” and beats up the homeless with his “droogs.” It is important to understand that Alex takes immense aesthetic pleasure in his crimes, elevating his violent acts to the status of high art, as exemplified in his admiration of classical composers, especially Beethoven. Music and brutality go hand in hand for Alex, and both mediums of expression are direct and sensuous for him. This is eventually used against him during the state-funded Ludovico treatment, which employs mind control and brainwashing to make Alex averse to the two things he loves: violence and Beethoven.

Moreover, Alex believes that evil is a natural state that exists within humanity, a viewpoint that is opposed by institutions of power and control in the film, namely the prison system and the psychiatric circle that aims for scientific advancement via forced reformation. Hence, the State is a direct challenge to Alex’s sense of self, his autarkia, as it deprives him of real choice and encroaches on his freedom as an individual. When viewed from this particular lens, Alex represents the struggle between free will and the forces of control, power, and reformation that hide seedy underbellies of their own.

Was Alex DeLarge Cured At The End Of A Clockwork Orange?

Condition-reflex therapy, including subliminal torture and manipulation, like the one Alex undergoes in the film, seldom aims at genuine rehabilitation and usually caters to the appearance of normalcy, ignoring the complexity of the human condition instead. As these methods incorporated Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which happens to be Alex’s musical ambrosia, he develops an aversion to the very things that constitute his sense of being. Kubrick commented the following about A Clockwork Orange, which is a film that examines the eternal tussle between nature and nature:

“A social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioral psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government, to use to impose vast controls on its citizens, and turn them into little more than robots.”

Hence, Alex’s “reformed” attitude, or goodness, is not inherent or voluntary — it is merely a psychological compulsion hardwired through dubious means. Alex becomes the titular clockwork orange, a mechanical puppet with an organic core, used and manipulated by conflicting political forces for their own vested interests. The Ludovico “cure” becomes the root of true sickness instead, acting as a society-imposed neurosis that prompts Alex to attempted suicide. However, the treatment fails, as Alex inadvertently reverts back to his core self, as he contemplates violence to Beethoven’s Ninth, and fantasizes about having sex amid a group of elite onlookers. He ironically muses, “I was cured after all,” which points to the fact that Alex hasn’t changed at all, and he looks forward to carrying out his violent tendencies to a certain extent within the dynamic confines of societal approval and acceptance.

What The Ending Of A Clockwork Orange Really Means

A Clockwork Orange ends on a controversial note, as it wildly differs from that of the original novel, which is similar to Kubrick’s changes to Stephen King’s The Shining. While Burgess’ Alex is a victim of the state, Kubrick’s Alex is an accomplice to the state’s machinations, wherein he agrees to cooperate with state-imposed limitations in exchange for socially-acceptable delinquency. Kubrick omits most of the novel’s ethical actions, providing a cruel, albeit realistic verdict of humanity, the nature of good and evil, and what it means to function in a society that disregards the very foundation of the human soul.