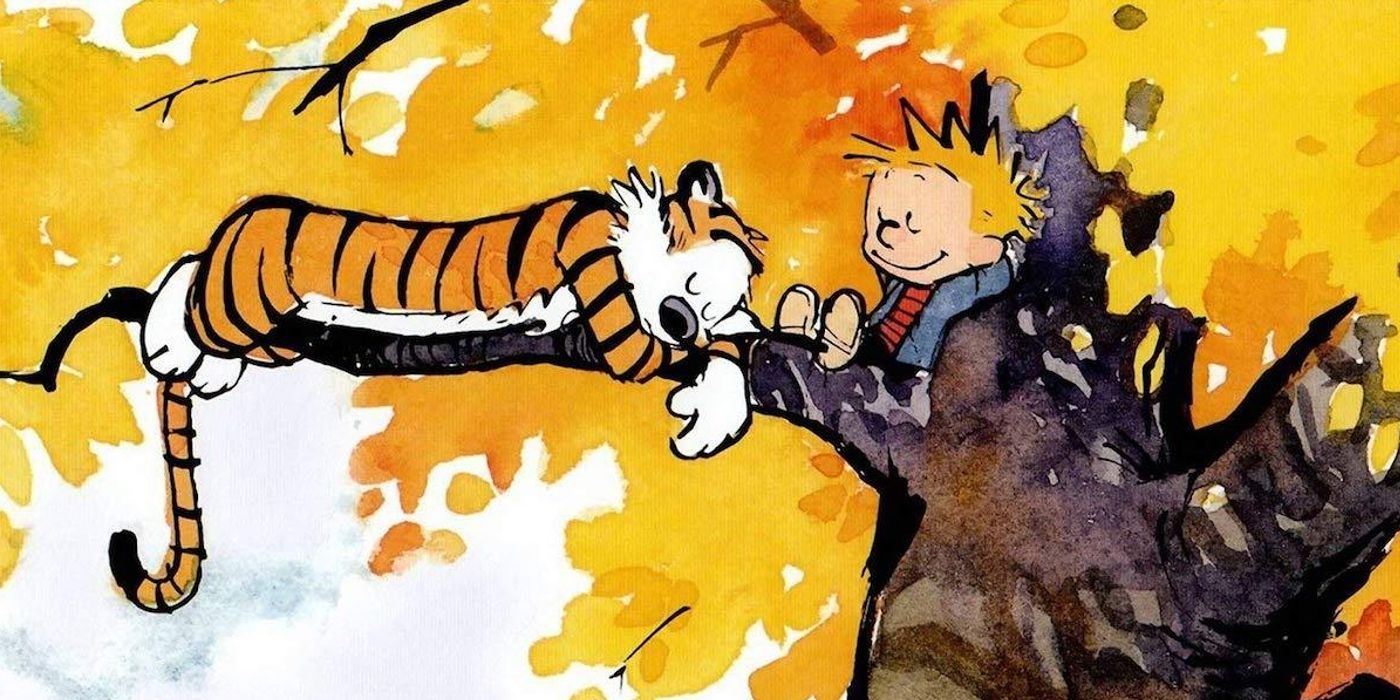

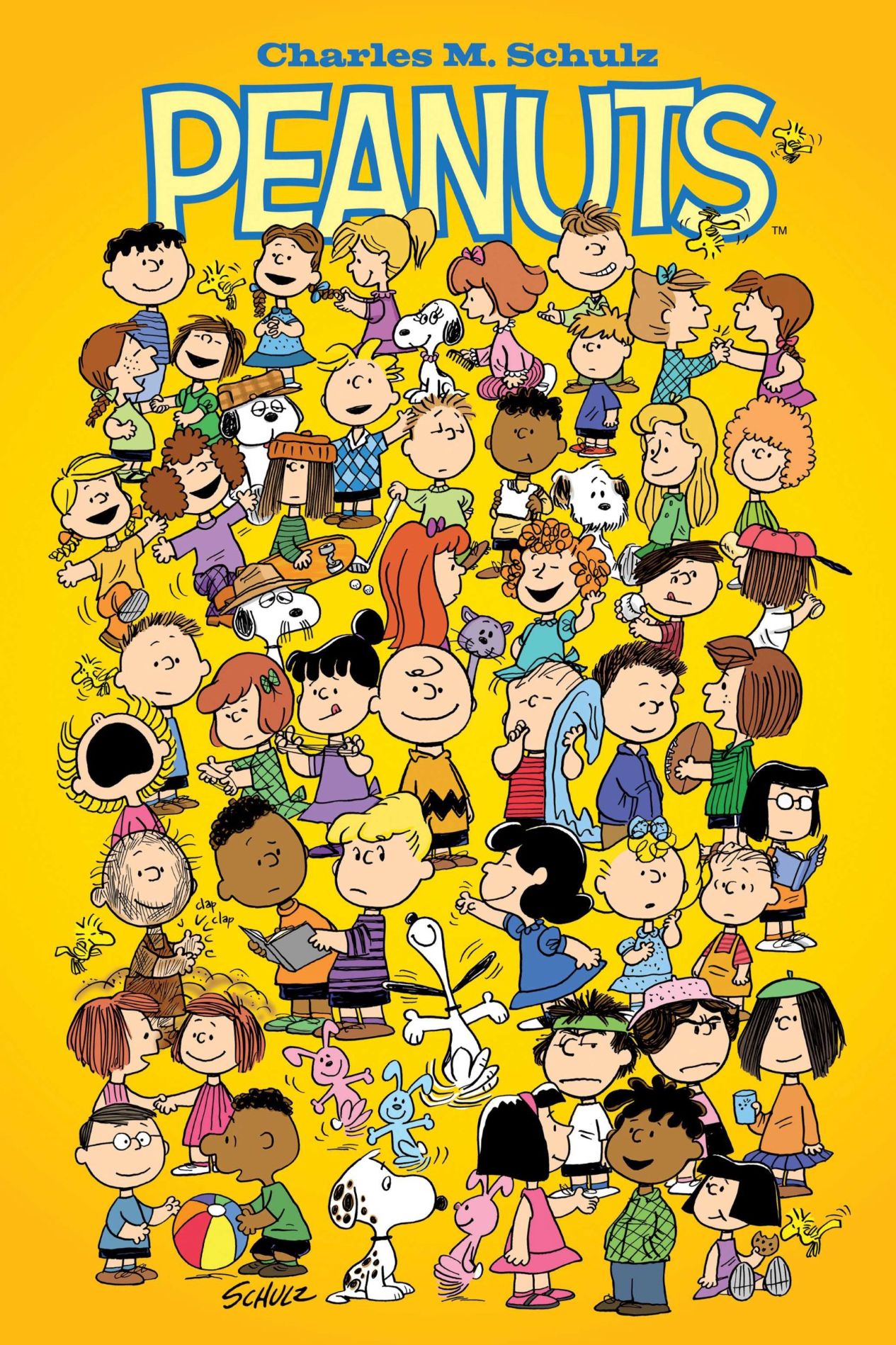

Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson was never shy about how indebted he was a cartoonist to Charles Schulz, the groundbreaking artist behind Peanuts – something a biography of Schulz essentially distills down to two critical lessons Watterson took from the older artist. By looking at both, readers can develop a clearer sense of why Peanuts and its creator were monolithic in the comic industry for so long.

In author David Michaelis’ Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, Bill Watterson is quoted in detail regarding Peanuts influence on his work, including the most valuable lessons he took from his formative reading of Charles Schulz’s strip. The Calvin and Hobbes author spoke unequivocally about his love for Peanuts, though the book noted that there was one key point on which he diverged from Schulz.

In a way, Watterson extracted the key to writing a successful comic strip from Peanuts, while at the same time, he defined his stance against commercializing his art in contrast to Charles Schulz’s.

Related

“That’s the Assumption Adults Make”: Calvin and Hobbes’ Creator Denies Hobbes Is Imaginary

Calvin and Hobbes’ creator Bill Watterson discusses the tiger in an interview and reveals why he feels that Hobbes is more lifelike than people think.

Peanuts Creator Charles Schulz Was A Huge Influence On Calvin and Hobbes

Bill Watterson’s Number One Creative Inspiration

Entering publication in 1950, Peanuts spent the next several decades ascendant in comics. Writer and artist Charles Schulz was an innovator in terms of content, as well as the form of his strip. By the 1960s, when the comic’s beloved animated adaptations began to be released, Peanuts was already a fixture in American popular culture – and would remain so for the remainder of the 20th century. It was in the 1970s and ’80s, however, that the first generation of comic artists raised on Peanuts began to produce work that bore the mark of Charles Schulz’s influence.

One of these creators was Bill Watterson, whose strip Calvin and Hobbes debuted in 1985. During just a decade in publication, Watterson’s comic managed to develop a fanbase, and achieve a level of notoriety, that placed it in the same creative stratosphere as Schulz and Peanuts, along with comics like Jim Davis’ Garfield and Gary Larson’s The Far Side. As Watterson explained, he and all of his creative peers were working in the shadow of Charles Schulz. Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography quotes him as saying:

I think what’s really happened is that Schulz, in Peanuts, changed the entire face of comic strips, and everybody has now caught up to him. I don’t think he’s five years ahead of everybody else like he used to be, so that’s taken some of the edge off it. I think it’s still a wonderful strip just in terms of solid construction, character development, the fantasy element — things that we now take for granted.

Though Calvin and Hobbes diverged stylistically from Peanuts during its run, Watterson attributed his fundamental understanding of humor to Schulz’s strip. Ultimately, this was one of two major ways in which Bill Watterson’s contributions to the comic medium were defined by Calvin and Hobbes relationship to Peanuts. More generally, the younger artist’s career trajectory wound up taking a vastly different path than his idol’s, given Watterson’s contrary views on the commercialization of art. In turn, this was part of what made Calvin and Hobbes run so brief, in comparison to its predecessors’.

Peanuts’ Most Important Lesson For Cartoonists, According To Bill Watterson

Charles Schulz’ “Emotional Edge”

According to Schulz and Peanuts, Bill Watterson’s conception of what a comic strip could be, and what its humor could achieve, was shaped by his early reading of Peanuts. As the book states:

The most important lesson for the future cartoonist was that “a comic strip can have an emotional edge to it and that it can talk about the big issues of life in a sensitive and perceptive way.

In other words, Watterson took the idea from Peanuts that humor could be simple and straightforward, without being banal or meaningless. He would go on to apply this “emotional edge” with great effectiveness throughout Calvin and Hobbes – a strip that regularly showed as much reverence toward life as it did irreverance toward parental control.

Calvin and Hobbes

Calvin and Hobbes was a satirical comic strip series that ran from 1985-1995, written, drawn, and colored by Bill Watterson. The series follows six-year-old Hobbes and his stuffed Tiger, Calvin, that examines their lives through a whimsical lens that tackles everyday comedic issues and real-world issues that people deal with.

Like Charles Schulz, Bill Watterson was “sensitive” to the world in many ways, which invariably informed the day-to-day subject matter of his comic strip. Their artistic work on the page can be scrutinized to find a number of parallels – beyond just the use of children and talking animals as protagonists. However, it is the similarities and differences between the two as artists that offers a unique degree of insight into Calvin and Hobbes and Peanuts, and what made them pop culture icons.

On a creative level, Bill Watterson followed in Charles Schulz’s footsteps as a loyal devotee, especially early in Calvin and Hobbes’ run. When it came to the business side of things, though, Watterson dramatically disagreed with his mentor’s commercialization of Peanuts. As author David Michaelis describes it in Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, this was the second most valuable lesson that Watterson learned from Schulz – except in this case, he realized what he did not want to do, in response to what Schulz and other cartoonists were doing.

Bill Watterson Refused To View Cartoons As A Commercial Product

An Artistic Principle

While Charles Schulz and other contemporaries – notably Garfield creator Jim Davis – became phenomenally rich as a result of licensing their creations in the 1980s and 1990s, Bill Watterson refused to sell the merchandising rights to Calvin and Hobbes. He openly spoke against the practice, suggesting that it went against the driving ethos of writing comics, which he considered making people laugh, rather than selling them something. According to Schulz and Peanuts:

Following Schulz’s example in one important way, Watterson rejected it in another. He devoted himself to the comics as an art form, taking his readers’ daily attention as “an honor and a responsibility,” and tried each morning to give them the best strip of which he was capable.

By contrast, Schulz saw comics as a kind of “competition” for the reader’s attention, and consequently, felt that the winner of such a competition should be able to profit.

It is worth noting, however, that despite their radically different conclusions on the commercialization of comics, Watterson and Schulz still ended up in the same place: at their desk. Both artists remained committed to producing their work by themselves, even when their success would have allowed them to farm out the production of Calvin and Hobbes and Peanuts. From Schulz and Peanuts:

Because he regarded cartooning as a highly personal form of expression, he, too, refused to hire assistants, working alone, drawing every line himself and painting special art for each of his books. But this was also why Watterson refused to “dilute or corrupt” his strip’s message with merchandising. “] want to draw cartoons,” he said, “not supervise a factory.”

In the end, Peanuts was essential to Watterson’s development of this position, due to his deep reservoir of love for it.

Michaelis also quoted Watterson as saying: “I went into cartooning to draw cartoons, not to run a corporate empire.” In effect, that is exactly what creators like Charles Schulz and Jim Davis turned their respective strips into massive, global businesses, which they oversaw directly themselves. As much as Bill Watterson learned the fundamentals of success as a comic writer from Charles Schulz, once Calvin and Hobbes achieved its own iconic status, its creator defined his approach to the industry in stark contrast to what Schulz managed with Peanuts.

Source: Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography

Peanuts

Created by Charles M. Schulz, Peanuts is a multimedia franchise that began as a comic strip in the 1950s and eventually expanded to include films and a television series. Peanuts follows the daily adventures of the Peanuts gang, with Charlie Brown and his dog Snoopy at the center of them. Aside from the film released in 2015, the franchise also has several Holiday specials that air regularly on U.S. Television during their appropriate seasons.