The western is a cornerstone of American cinema and, from Shane to The Searchers, many of those early, seminal, genre-defining westerns still hold up today. Filmmakers have been mythologizing the Old West for as long as they’ve been telling stories on film. Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, one of the first narrative films ever made, released in 1903, laid out the tropes and conventions of the western genre.

Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon introduced a moralistic edge to the typically violent genre. Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars introduced a bleak, brutal Italian take on the American western. George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid introduced a style of anti-western that switched out glorified gunslingers for bantering train robbers. A lot of these early western movies are timeless gems that are just as entertaining today.

Related

10 Most Dramatic Shootouts In Westerns, Ranked

From Shane to The Wild Bunch to The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, there are some truly thrilling shootout sequences in classic Western movies.

10

The Great Train Robbery

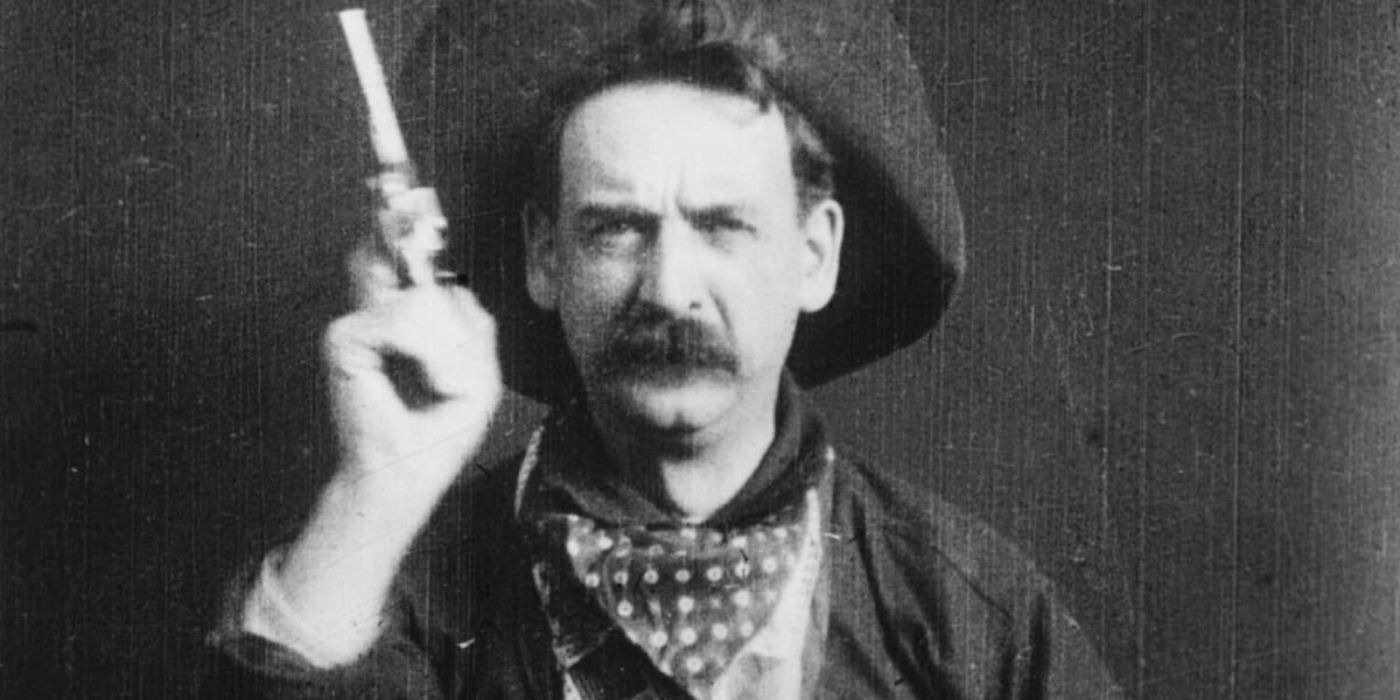

Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 gem The Great Train Robbery is often erroneously called the first western movie ever made. That title actually goes to a British short from 1899 called Kidnapping by Indians. There were also a handful of Edison company films that experimented with western tropes before Porter made his film. But The Great Train Robbery was the first to establish the western movie formula as it’s known today: crime, followed by pursuit, followed by swift justice.

The quick camera pans, use of filming locations, and bursts of violent action made The Great Train Robbery a more dynamic movie than contemporary audiences were used to. It went a long way towards creating the cinematic language that would make narrative films a popular form of entertainment. The closeup of Barnes emptying his gun into the camera is so iconic that Martin Scorsese recreated it as the final shot of Goodfellas.

9

Stagecoach

John Ford directed a lot of seminal westerns in his day – My Darling Clementine, Fort Apache, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – but his most groundbreaking contribution to the genre was 1939’s Stagecoach. The story is simple: a group of people traveling across the desert have to band together and fight for their survival when their coach is attacked. Stagecoach’s high-octane spectacle introduced the western’s ability to provide an action-packed viewing experience.

Stagecoach introduced John Wayne’s screen image as a heroic gunslinger and Ford’s penchant for capturing breathtaking shots of Monument Valley. The movie has some common problems for its time period – its portrayal of Native Americans as violent savages has drawn plenty of valid criticism – but its revolutionary action filmmaking still holds up today. Its pacing is fast and snappy even by modern standards.

8

Red River

Howard Hawks’ fictional account of the first cattle drive from Texas to Kansas, Red River, is a more or less conventional western. But it proved that the western genre could be used for more than just exhilarating action sequences; it demonstrated that a western movie could also be a poignant character piece. The movie digs a lot of engaging tension out of the disagreements between John Wayne’s Texas rancher and his adopted adult son, played by Montgomery Clift.

Wayne and Clift have one of the most captivating character dynamics in the entire western genre in Red River. Russell Harlan’s cinematography realizes the full beauty of the frontier landscapes that the cattle drive traverses throughout the film. Red River proved that westerns don’t have to just be about cowboys getting into gunfights; they can be about anything, including a strained father-son relationship.

7

High Noon

Before Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon, western movies depicted their heroes as stoic and fearless. When danger came knocking, they were ready to nobly face the music. But in High Noon, when Gary Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane is faced with the challenge of taking on an entire gang alone, he entertains the idea of fleeing town with his wife. A character who’s afraid to die is much more human and relatable than a hardened killer.

At the time, audiences were disappointed by High Noon. They were expecting the usual shootouts and fistfights and what they got instead was a lot of moralistic dialogue and a supposed hero frantically asking around town for help. But it’s since been reappraised as a masterpiece. It’s not a traditional western, but it’s something more profound; it’s about a crisis of conscience.

6

Shane

George Stevens explored the dark side of the gunslinger archetype in Shane. In previous westerns, the gunslingers who shot down the bad guys were hailed as courageous heroes and carried around on the townspeople’s shoulders. But Shane explored the notion that these gunslingers might not have felt so great about themselves, and showed the psychological toll that a life of killing would have on these hired guns with blood on their hands.

Alan Ladd’s iconic performance as Shane dug deeper than any past trigger-happy western movie star. He paved the way for nuanced western movie performances like Warren Beatty’s John McCabe in McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Clint Eastwood’s William Munny in Unforgiven. His closing “no living with a killing” monologue is one of the best-written and best-acted monologues in movie history, resolving the themes of the story perfectly.

5

A Fistful Of Dollars

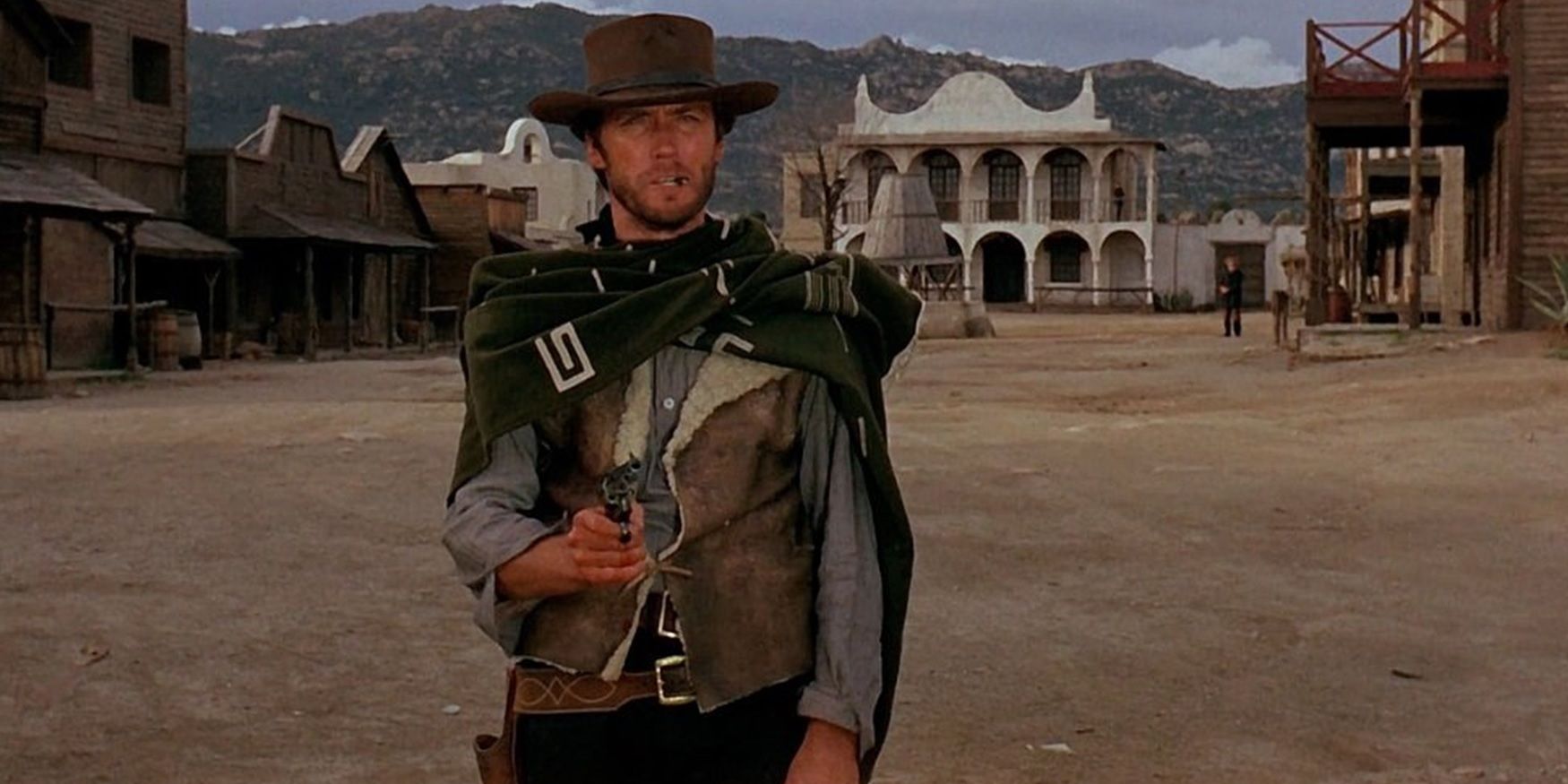

For the first few decades of its existence, the western was exclusively an American genre. But before long, filmmakers overseas were inspired by those American westerns. Akira Kurosawa translated Ford’s stories of American gunslingers to his own stories about Japanese samurai, and Sergio Leone remade Kurosawa’s Yojimbo within his own uniquely bleak and bloody vision of the Wild West in A Fistful of Dollars. With Fistful, Leone singlehandedly created the spaghetti western.

A Fistful of Dollars was quickly followed by other essential spaghetti westerns like Sergio Corbucci’s Django – not to mention its own sequels, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly – to solidify the grisly Italian western as a subgenre of its own. Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name antihero became one of the most popular archetypes in the entire western canon. Leone’s satirically exaggerated, operatic violence introduced a whole new cinematic language to the genre.

4

Rio Bravo

Hawks’ masterfully crafted 1959 hangout western Rio Bravo is a western made in response to another western. Hawks and his leading man Wayne were horrified by High Noon’s blasphemous upending of the American ideals. As far as they were concerned, a true American hero wouldn’t run scared and ask everyone around him for help in a panic; a true American hero would stand up to the bad guys without a hint of fear. So, they made a movie about just that.

In Rio Bravo, Wayne’s Sheriff John T. Chance locks up a notorious outlaw and learns that in a couple of days, the outlaw’s gang will come to town and try to break him out. Instead of panicking like Gary Cooper in High Noon, Chance just kicks back and gets to know his new deputies while he awaits the gang’s arrival. Rio Bravo was the first dialogue-driven western, and it worked spectacularly.

3

The Searchers

While Stagecoach is arguably Ford’s most groundbreaking western, The Searchers is arguably his greatest western. Wayne once again stars as Ethan Edwards, one of the most fascinating and three-dimensional characters he ever played. Ethan is a Civil War veteran who feels redundant in a post-war world. But when his niece is abducted, he spies a chance to put his violent skills to good use one last time, so he rides off into the desert to save her.

The shot of Wayne framed in the doorway, looking from the outside in at a peaceful life he could never lead himself, is one of the most iconic images in cinema history. It encapsulates the themes of the story: a man out of his time, not just searching for a missing girl, but searching for a purpose. The Searchers has inspired everything from Lawrence of Arabia to Taxi Driver.

2

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid

William Goldman’s screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid flew in the face of western genre conventions. It’s not about noble lawmen who foil train robberies; it’s about the perpetrators of the train robberies. The heroes don’t stand strong and face down the villains; they flee to Bolivia. With this beautifully subversive script, Goldman created the “anti-western,” a perfect antidote to the tired, conventional, formulaic westerns that had flooded multiplexes throughout the 1960s.

George Roy Hill directs the film with a modern comedic clip and Paul Newman and Robert Redford anchor the movie with their endearing on-screen chemistry in the title roles. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was a game-changer in the western genre and one of the key early entries in the New Hollywood movement. It’s more of a buddy comedy than a standard western.

Related

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid & 9 Other Classic A-Lister Team-Ups

A Hollywood film is lucky to let one huge actor, let alone two. When that happens, like in Butch Cassidy and Thelma and Louise, movie magic happens.

1

The Wild Bunch

Sam Peckinpah’s blood-drenched 1969 western epic The Wild Bunch tore up the playbook. It’s an anarchistic, ultraviolent masterpiece that upends every established hallmark of the western genre. William Holden and Ernest Borgnine lead an ensemble of aging outlaws planning one last job. Peckinpah’s depiction of old-school gunslingers struggling to adapt to the ever-changing modern world of 1913 – a more civilized time when their trigger-happy antics have become outdated – provided the perfect swansong for the traditional western.

The use of quick-cut editing and glorious slow-motion in The Wild Bunch’s action scenes has since been copied by dozens of filmmakers, but it was a technical revolution in 1969. The Wild Bunch is one of the roughest, meanest, bloodiest westerns ever made. It’s a truly uncompromising vision of the ugliness of the Old West, and it’s just as shockingly brutal today as it was half a century ago.